“We have bears here?” Ranger Ison Lin says, mimicking the guests he often guides along the 14-kilometer Walami trail, one of Yushan’s most popular hiking routes. Ison belongs to the indeginous Bunun people grew up in the forests and mountains of Yushan trapping and hunting just about everything that moves – and that included two black bears that Ison shot when he was a young man, kills that made him famous in his youth.

“That was a long time ago, now I only shoot with my camera,” says Lin, who has been a park ranger almost since the park was designated.

ABOVE: The Formosan black bear.

In the heat of the summer months, travelers and many of Taiwan’s more adventurous citizens seek out the fresh air and cool waters of the nation’s parks and forest reserves along the mountainous spine that runs the length of the island nation, among them Yushan National Park. Yushan – which translates to ‘jade mountain’, so called for the rich green of it’s forested interior – is criss-crossed with all manner of hiking trail. But Yushan isn’t just an escape for hikers; it’s also one of the few places left in Taiwan where wildlife can still live free.

Park tours can lead to sightings of tree dwelling macaques, Reeves muntjac – a diminutive member of the deer family,snakes in abundance and a multitude of birdlife including the rare Taiwanese blue pheasant. Much less likely to be spotted by a casual hiker is a member of the last known populations of Formosa black bears in existence. Numbering somewhere between 200 and 600 animals living in the wild, the Formosa or Taiwanese black bear is the largest animal in Taiwan, an apex predator that has recently gained a lot of publicity. Still most citizens of the country have no idea that bears still roam it’s forests.

ABOVE: Lin points out places where bears have left claw marks on trees foraging for honey and insects along the trail.

These days Lin spends time sharing a lifetime’s worth of knowledge about the park with visitors eager to learn about the animal life. Lin points out places where bears have left claw marks on trees foraging for honey and insects along the trail and explains to tourists what to do if they ever come across a bear in the wild.

For all of Lin’s accumulated knowledge of the park’s territory and wildlife, it takes a research scientist like Mei Hsiu Hwang associate professor and director of the Institute of Wildlife Conservation – or mama bear as she has become known for her dedication to the animals survival – to make the public aware of the bears’ plight. Mei Hsiu Hwang who jokes that she returns more often to the rugged research areas of Yushon’s mountains than to her parents’ home is credited with tagging and tracking 15 adult bears in the area. Her most generous estimate for the wild bear population is about 800 animals, which she estimates needs to increase to at least 2,000 if they are to be sustainable.

Mei Hsiu Hwang’s efforts have raised the general public’s conscience of the park’s wildlife, especially its bear presence which has inspired local guides to open bear walking tours along the park’s trails. Unlikely to spot any big mammals, hikers who take on the 90 kilometer Battonguan trail are certain to be treated to other spectacles like Nanan waterfall where hikers come to bathe in its fresh pool during the hot months and drink the clear water all year round.

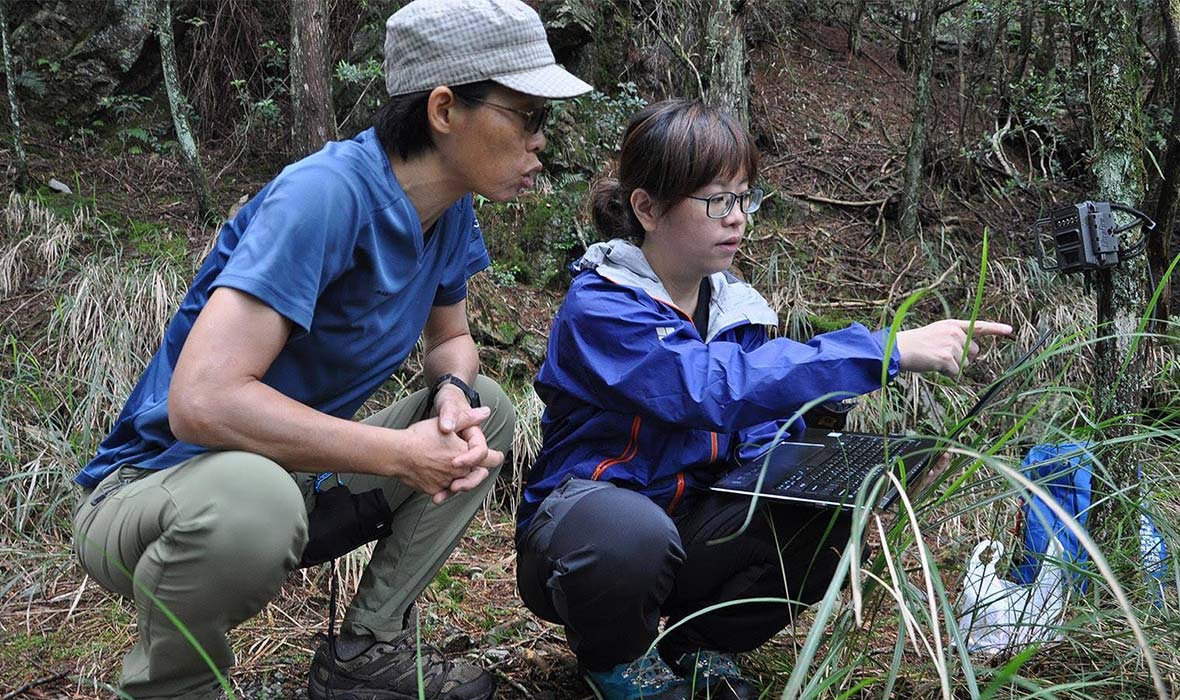

ABOVE: Checking camera traps.

The Battongguan trail was cut during Taiwan’s colonial era when Japan’s Imperial Army followed an ageless pedestrian highway the island’s indigeious people had traveled on for millennia. Ironically the Japanese army widened and posted checkpoints along the path as part of their effort to control the very people who had created it. Today those abandoned outposts have all but been reclaimed by the forest and the trail returned to its original pedestrian state. Wildlife has made a slow comeback in the most remote areas of the park.

Part of the mission to conserve the Formosan black bear has been public awareness. The ‘moon bear’, as it is sometimes known for the identifying white crescent on the animals chest, has become recognized as the national animal and Taipei has adopted a caricature with the bear’s distinct Mickey Mouse like ears named ‘Bravo’ as it’s official mascot.

Professor Hwang and ranger Ison Lin warn against allowing wild places like Yushan National Park becoming too civilized, too easily accessible. As Hwang explains, bears need large areas of territory to thrive and so their numbers reflect the health of the entire park and all of the other animals that live within it.

Though strictly protected today black bear paws were once considered a delicacy and their bile and other internal organs were (and are) used in traditional Chinese medicines.

“Black bear conservation efforts have not succeeded yet, if they had, why was a bear found with its paws chopped off just last year at the bottom of the Lakulaku River?” Mei Hsia Hwang asks.

The peak of Yushan mountain at 3,952 meters is the highest point in Taiwan from which on a clear day it’s possible to see coastlines far in the distance, beyond what seems to be a never ending canopy of dense forest. Summiting takes experience and dedication, but as trekking becomes ever more popular in Taiwan, more and more hikers are visiting Yushon in recent years. Many of whom come with hopes of glimpsing one of the nation’s largest animals. The Formosan black bear however is still thinly populated on the ground; chances of seeing one are almost none – for now.

“Bears are a flagship species. They’re big, like a star, like pandas, elephants, and tigers. If the Formosan black bear continues to be ignored, it could end up facing the same fate as the clouded leopard and the river otter,” Hwang says, referring to two other of Taiwan’s mammals now believed to be extinct.