The bells on the rickshaws ring so often and so regularly that it sounds like pleasant, metal rain. It’s easy to imagine shouting, and pushing, and honking in the photos – but, in reality, the sound of Dhaka traffic is the sound of pleasantly tinkling, politely ringing bells. The streets of Dhaka are chaos, but it’s a meditative chaos.

Standing over the angular buildings that make up downtown Dhaka, one feels the humans pumping through the city: standing on their rickshaws to stare over trucks, poles slung over their shoulders to balance the weight, kids dancing through the traffic. At the pier, the human tumult continues to the water where boatmen smile and hawkers bark. On the floor of the markets, excess produce is trampled and forgotten. The city Dhaka does many things. But it never stops.

There are nine million people in Dhaka, and they all need to be somewhere.

Journalist William Langewiesch wrote in The Outlaw Sea that, “Bangladesh is not so much a nation as a condition of distress” – a sentiment shared by Jody Rosen, who wrote “The Bangladeshi Traffic Jam that Never Ends.” Sometimes the streets flood to knee height, other times there’s nothing wrong whatsoever; it doesn’t really matter because the traffic jam in Dhaka never lets up.

There is no key to getting around Dhaka, no shortcuts. There are nine million people in Dhaka, and they all need to be somewhere. That said, it works. It has to. The relatively courteous traffic, easy-access street-side stalls and markets, and general understanding that the Dhaka traffic is a cruel mistress means that there’s a sense that everyone is working together to get somewhere – whether or not that’s true.

ABOVE: Filming in Dhaka can be challenging but also incredibly fun. Normally, when one is filming, it’s with a sharp, expectant focus. In Dhaka, it’s important to just let the chaos flow by your lens – and to watch out for rickshaws.

The end result of this coalescing of chaos is the ringing, colorful streets. No doubt, they are a nightmare for logistics and city planning, but it’s a fittingly colorful photo opportunity. The people on the streets seem to make do with whatever modes of transportation they can, and the street always seems so very alive. Each passing scene of rickshaws, cars, and people is visually unique.

I imagined that this pandemonium – the curious chaos of the commute – seeped elsewhere into the lifeblood of Dhaka and was interested to see the effects on the water. I took a car from my centrally-located hotel, located in the north of the city, to Dhaka River Port in the south. It took three hours.

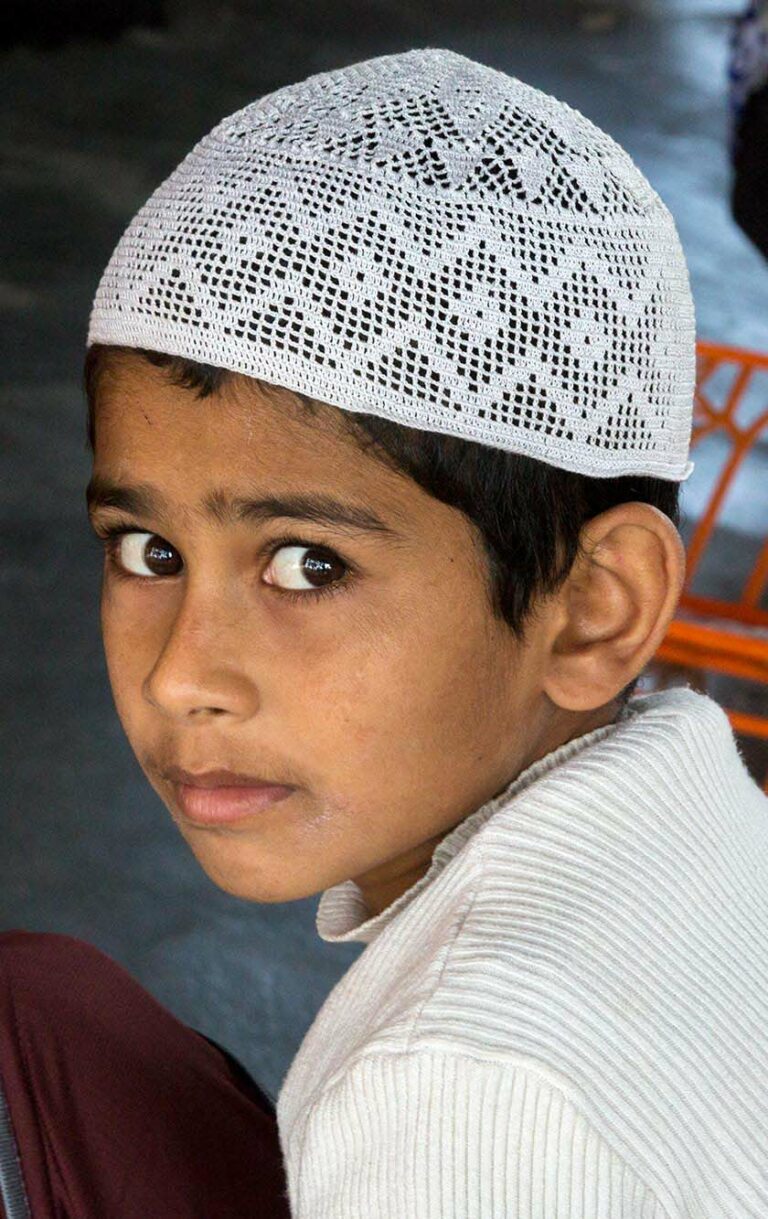

On the pier, in the streets, at the market, and in my car, the sight of tourists is a rare one, and the locals don’t make a secret of their curiosity.

The Dhaka River Port meets at a confluence of streams and estuaries of the Buriganga River, which eventually flows into the mighty Meghna and then out to sea. From here, boats travel south; routes from Dhaka lead to Madaripur and Gourmadi-Torki – into the Meghna River and out to sea.

The river finds itself, however, smack dab in the middle of a city of nine million people trying to cross the river for work, fun, or home. Here, at the Sadarghat, or city wharf, alongside riverside markets and bazaars, small boats carry produce, products, and people from one side of the river to the other. Literally tens of millions of passengers flow through here – along with tens of millions of tonnes of cargo. The seeming quiet of the bells of the traffic-heavy streets had turned into shouting, bartering, and laughing, a constant boom of voices.

ABOVE: Dhaka River Port, a site of commerce for hundreds of years, is just as hectic, if not more so, that the crowded streets of Dhaka.

One facet visitors to Dhaka will be quick to notice is that everyone seems to be staring at you. Veteran travelers will scoff at this all-too common trait of being a foreign face in a crowd. Don’t. On the pier, in the streets, at the market, and in my car, the locals don’t make a secret of their curiosity. Once, tying my shoe, I noticed about nine people watching. Among other problems, it made filming a bit difficult.

Large ferries linger and wait for passengers to chug down the river, and hawkers try to sell their wares. Indeed, the entire Sadarghat region is swarmed with people in a not dissimilar way to the streets: all needing to make their way, all knowing the hidden and unwritten rules of the waterways and boardwalk.

Commerce has brought travelers to the shores of Dhaka for centuries. Once upon a time, this crowded, loud, fascinating port was the reason Dhaka was dubbed the “City of Channels,” drawing money and minds from around Europe and Asia. The commerce that comes through here eventually makes its way to the city’s famous bazaars.

On the pier, in the streets, at the market, and in my car, the sight of tourists is a rare one, and the locals don’t make a secret of their curiosity.

The bazaars of Central and Western Asia are often tourist traps. Overpriced, handmade goods are thrust forward by overeager stall keepers and marketers. At Kawran Bazar, this is not the case. Kawran Bazar refers to a place rather than a market – indeed a business district that is quite posh in some places. But, it was the Kawran Bazar marketplace I sought.

I should connote that my visit to the Kawran Bazar had the perhaps destabilizing presence of a police officer, the “tourist police.” I was never quite able to find out why he was with me. But, just six months previous, ISIS/Jamaat-ul-Mujahideen affiliated attackers used bombs, machetes, and guns to take foreign and local hostages. Twenty-nine were killed. I heartily accepted the friendly police presence on my strolls through the Kawran Bazar.

ABOVE: Marketers sell their wares in giant mounds. This single bazaar hosts more than a thousand stalls.

As for what I was strolling on, it was a bit of everything. Produce and other detritus are dropped during the day, stomped by the near constant foot traffic into thin, paper-like strips that can be easily swept up.

Looking up, the full grandeur of the market is seen through bobbing heads of patrons and the full arms of delivery men. Mounds of produce lay on the floor as excited marketers smile and wave. This is the largest wholesale market in Dhaka and there are more than a thousand stalls – a thousand eager entrepreneurs, a thousand shops full of goods, and thousands upon thousands of shoppers.

ABOVE: The Kawran Bazar leads all the way to the train tracks and beyond. As locomotives chug by with passengers clinging to the surface, women sit by scaling fish, and delivery men carry their goods on their heads.

One brave enough walk to the east end of the Kawran Bazar will find that the bustle and trade of the market couldn’t be stopped with a train – literally. At the railway, trains roll by and people calmly scaling fish and peeling produce pull down their covers to let the trains – vintage-looking behemoths covered inside and out in human bodies – trundle through. This, for me, was the culmination of the Dhaka chaos; come what may, Dhaka does as it wills.

There is, of course, much more to compliment the city of Dhaka than its beautiful chaos: the food, the people, the language. But it was that special brand of bedlam that I found so intriguing – a city that’s desperately trying to move.

In the 17th century, this dingy capital was the heart of the Mughal dynasty, the Venice of the East, it was called – one of the richest and most prosperous cities on earth. Some of that history remains today: the tomb of Bibi Pari, the Bara Katra caravansary, the Hindu Dhakeshwari. That world status seems gone now. The great cities of Bangladesh’s neighbors have moved on to bigger things, better streets, and brighter hopes for the future. But, anyone who has sat motionless in the Dhaka traffic as dozens of rickshaws pass can tell you: Dhaka will find its way.