Covers with lipstick on suitcases, creeping spies up dingy night-blue alleyways, some cloying New York Times Bestseller from an actor — holiday beach reads can be a bit light. But, Southeast Asia is steeped in historical accounts from early explorers, and those in the Victorian era were at once vulgar and fascinating, the spirit of an explorer with ideas we today consider barbaric, a time of adventure botanists and globe-trotting imperial missions.

The history of Western 19th century explorers in Asia is brutal, unfair, and bloody. It is also, however, a chance to understand strange lands through worryingly familiar eyes. A warning to new readers of personal historical journals: Some of the language can be disturbing, some explicitly racist, some espousing political views that are thankfully quite dead, and some can just be tedious.

The origins of the Mekong, the theory of Darwinism, even the advent of tea farming — all had their origins in arrogant colonialists traipsing through land that was not theirs in search of riches and fame. Their motives and methods were abysmal. Their stories were still fascinating.

Travels in the Central Parts of Indo-China, Henri Mouhot

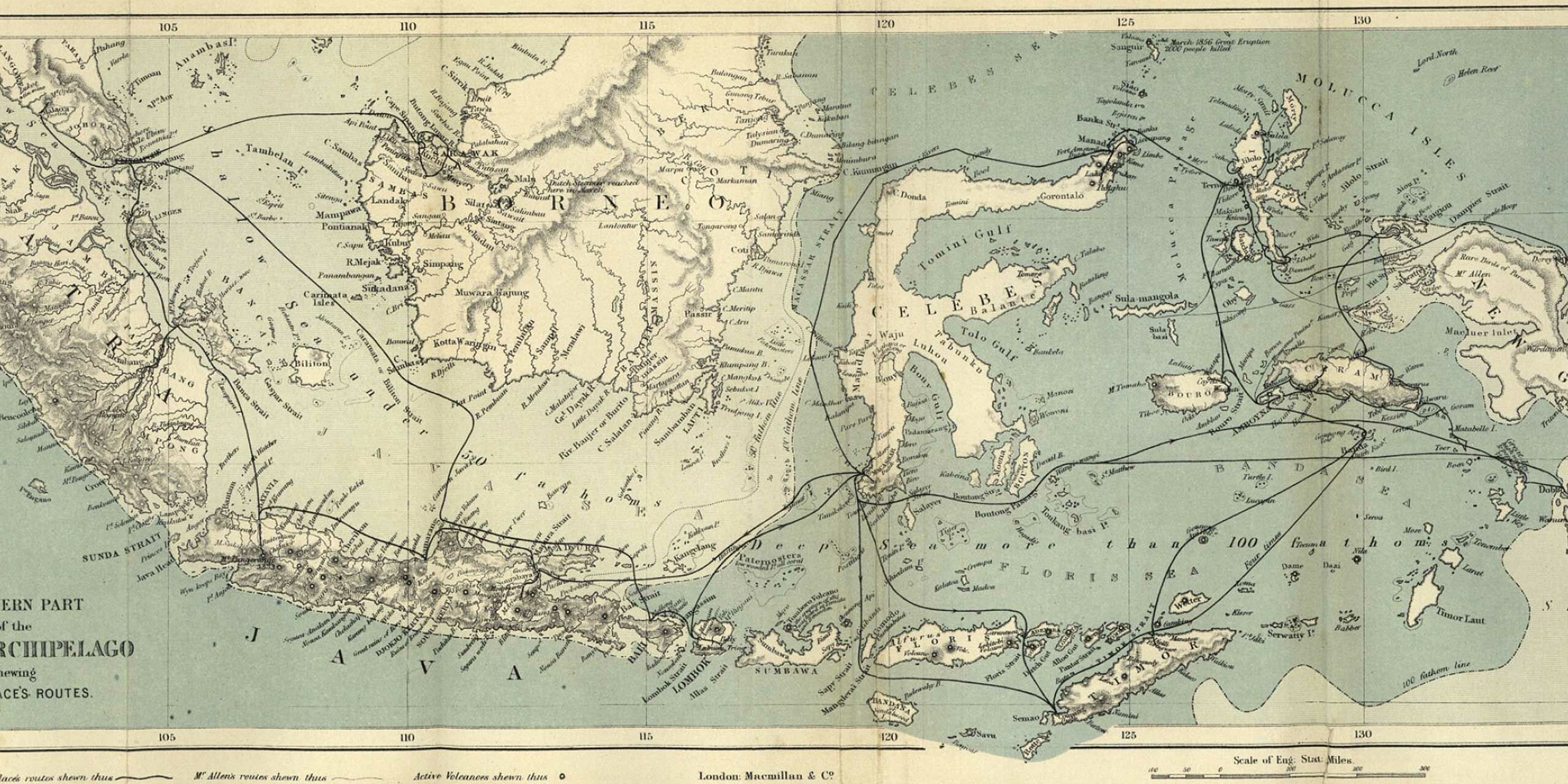

For decades, the name Henri Mouhot was synonymous with Angkor Wat. He didn’t “discover” it, though he is often credited with doing so. His drawings, descriptions, and first person accounts of Angkor Wat remain evocative.

“Sad fragility of human things! How many centuries and thousands of generations have passed away, of which history, probably, will never tell us anything: what riches and treasures of art will remain forever buried beneath these ruins; how many distinguished men—artists, sovereigns, and warriors—whose names were worthy of immortality, are now forgotten, laid to rest under the thick dust which covers these tombs!”

His work, Travels in the Central Parts of Indo-China: Siam, Cambodia, and Laos, During the Years 1858, 1859, and 1860 is often sold in two volumes, and readers will find his work on Angkor Wat in the latter half of the first volume, known there as Ongkor. The first volume also makes for great reading in Bangkok.

He is not the most compelling of writers. His tale, though, is more in line with a travelogue than most state-sponsored journeys through Southeast Asia, filled with hunting, conversation, and trials of the spirit. To the modern reader, like so many other colonial travelers, his descriptions of locals are unenlightened in the extreme, but he had a strange abiding love for Indochina.

Henri Mouhot’s travels would kill him in Luang Prabang, where a temple still stands commemorating the traveler. For an expedition that followed, try The River Road to China by Milton Osborne, mentioned down below. An all-time favorite Southeast Asia explorer story, this tracks the French expedition from Cambodia for a viable route via the Mekong to the riches of China.

The History of Malay Archipelago, Alfred Russel Wallace

“They were headhunters like the Dyaks of Borneo, and were said to be sometimes cannibals. When a chief died, his tomb was adorned with two fresh human heads; and if those of enemies could not be obtained, slaves were killed for the occasion. Human skulls were the great ornaments of the chiefs’ houses.” This, believe it or not, was part of a journey that brought us the Theory of Evolution.

Anyone who knows the history of Natural Selection — or has seen the recent BBC special from Bill Bailey — knows Alfred Russel Wallace. Charles Darwin and Wallace were searching for the same thing at the same time and had identified the same mechanism by which it occurs. They took very different routes.

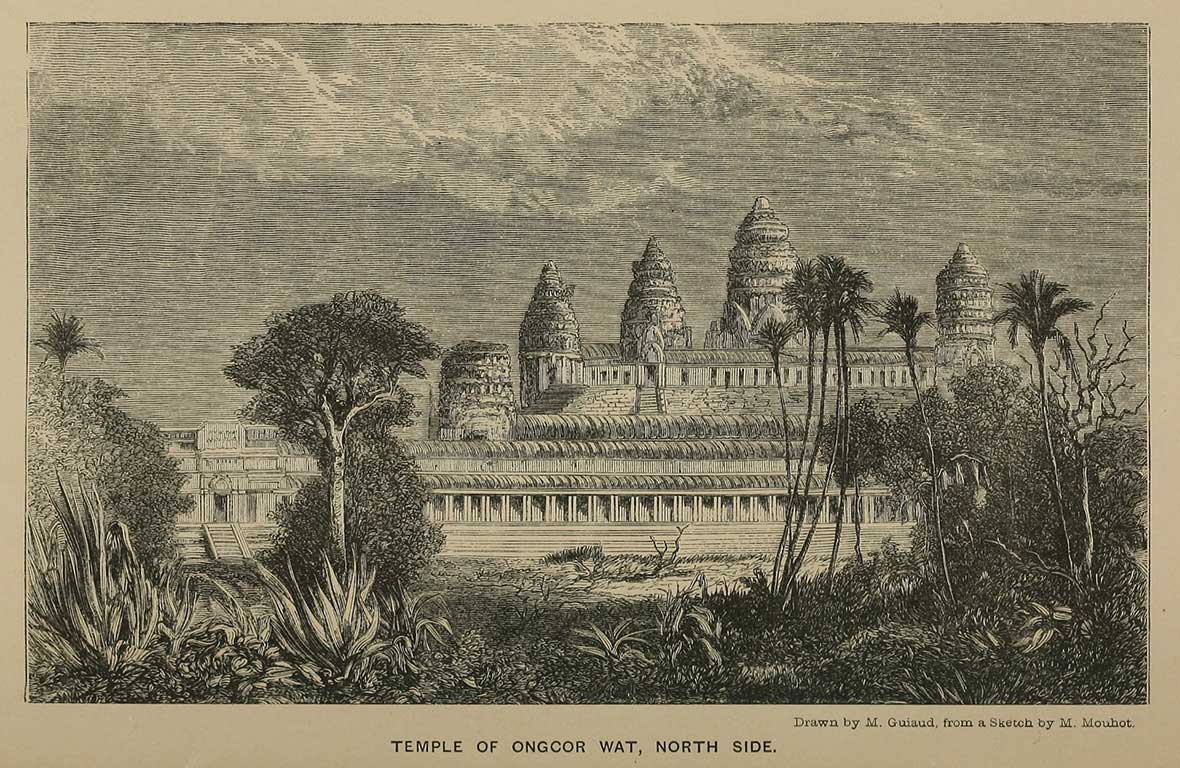

Where Darwin had the five years aboard the Beagle and the Galapagos, Alfred Russell Wallace took a longer path through the Amazon and Malay Archipelago. Wallace was a naturalist, yes, but also an explorer, a collector of rare birds, and an anthropologist.

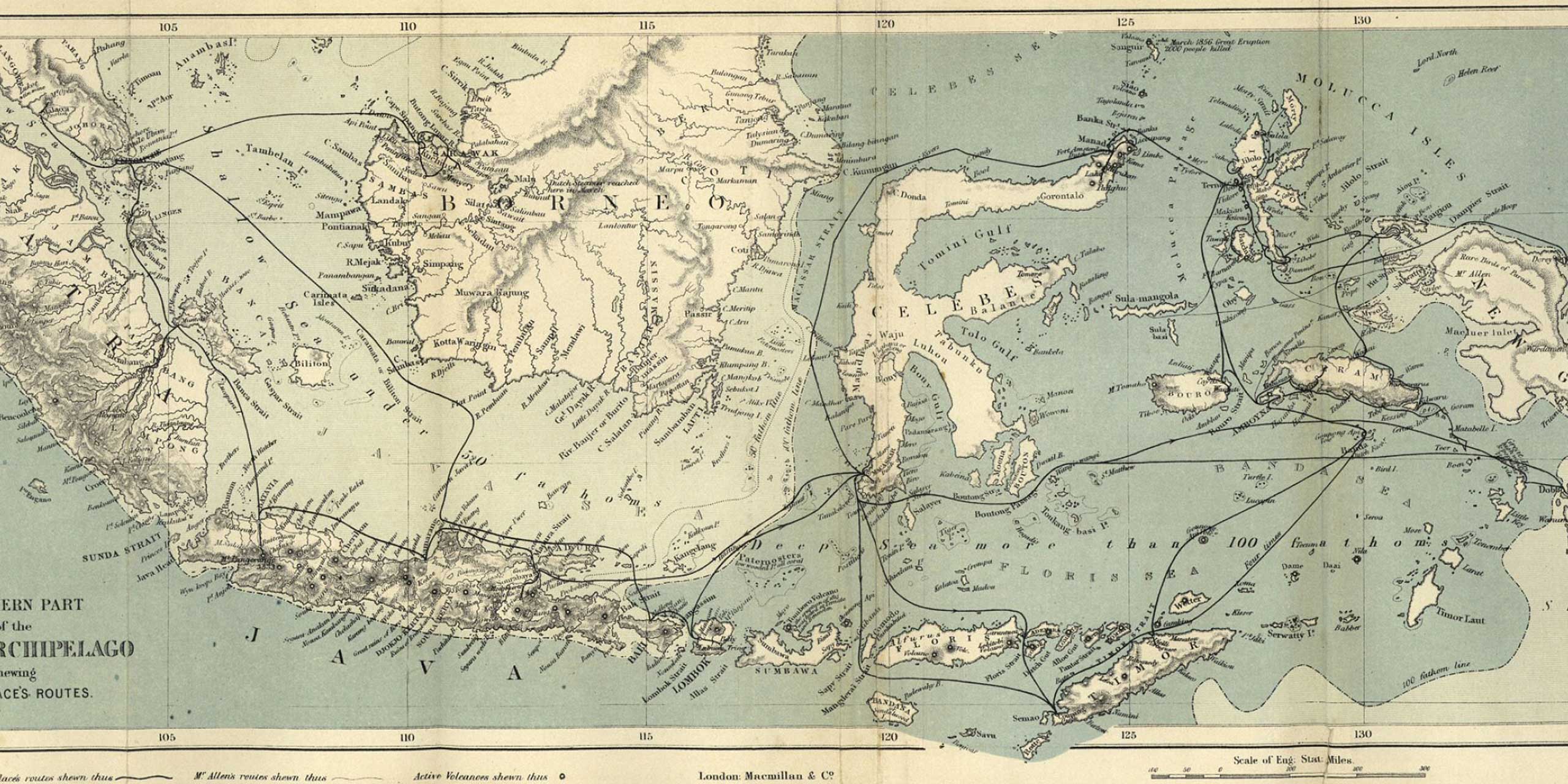

As Darwin poured over his beaks and beetles in England, Wallace searched for rare birds to send back home for money from Lombok, Papua, and beyond. His most important work came from the Maylay Archipelago, where he famously came up with the Wallace Line, the concept by which animals evolved from two distinct geographical regions.

However, beyond his contribution to science, this is considered one of the greatest Victorian travelogues ever written — the story of a man traipsing through Singapore, Borneo, and Bali in search of orangutans and birds of paradise is absolutely fascinating. And, unlike many other similar explorers, he’s fun to read.

“Hardly any of the people appeared to have seen a European before. One most disagreeable result of this was that I excited terror alike in man and beast. Wherever I went, dogs barked, children screamed, women ran away, and men stared as though I were some strange and terrible cannibal or monster. Even the pack-horses on the roads and paths would start aside when I appeared and rush into the jungle.”

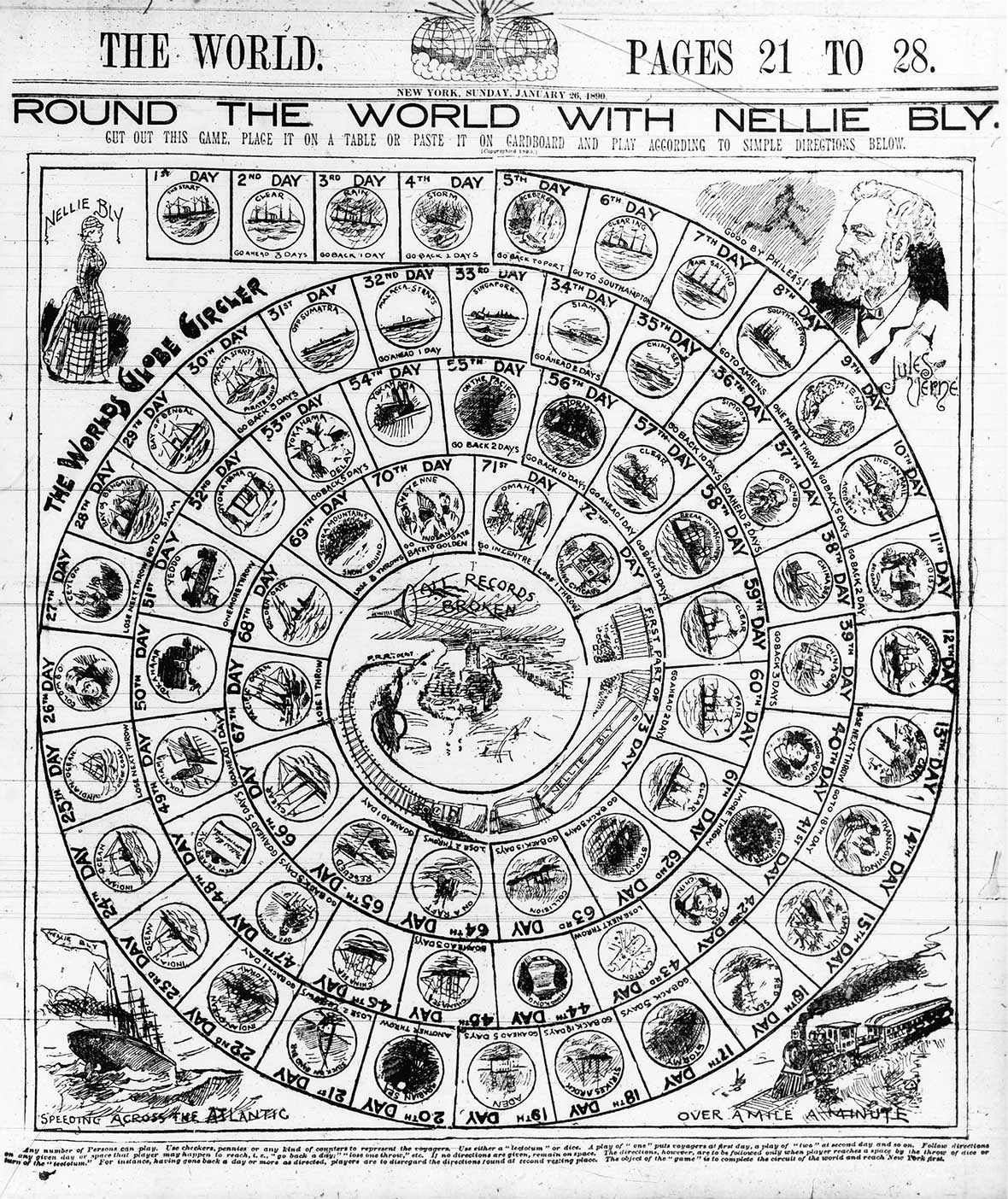

Around the World in Seventy-Two Days, Nellie Bly

Nellie Bly, simply put, the coolest person who ever existed. World’s first investigative journalist? Inventor? Millionaire? Novelist? If you’ve never heard of Nellie Bly, born Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman, be prepared for the Wikipedia clickhole of your life.

Her journey was not one of exploration, or naturalism, or colonialism — just good old fashioned ambition. Nellie Bly walked into her editor’s office in 1888 at New York World and said she wanted to beat the sci-fi novel, Around the World in 80 Days. A year later, she was off.

Now, obviously, this involves (mostly) non-Asia areas, but it’s a classic read that will see readers to Sri Lanka, Penang, Singapore, and Hong Kong. The above books can be informative but dry. This isn’t. It is fast, interesting, and quirky. Alfred Russel Wallace found 700 species of beetle in Singapore. Nelly Bly bought a monkey.

“We found the monkey-cage, of course. There was besides a number of small monkeys one enormous orang-outang. It was as large as a man and was covered with long red hair. While seeming to be very clever he had a way of gazing off in the distance with wide, unseeing eyes, meanwhile pulling his long red hair up over his head in an aimless, insane way that was very fetching.”

The River Road to China, Milton Osborne

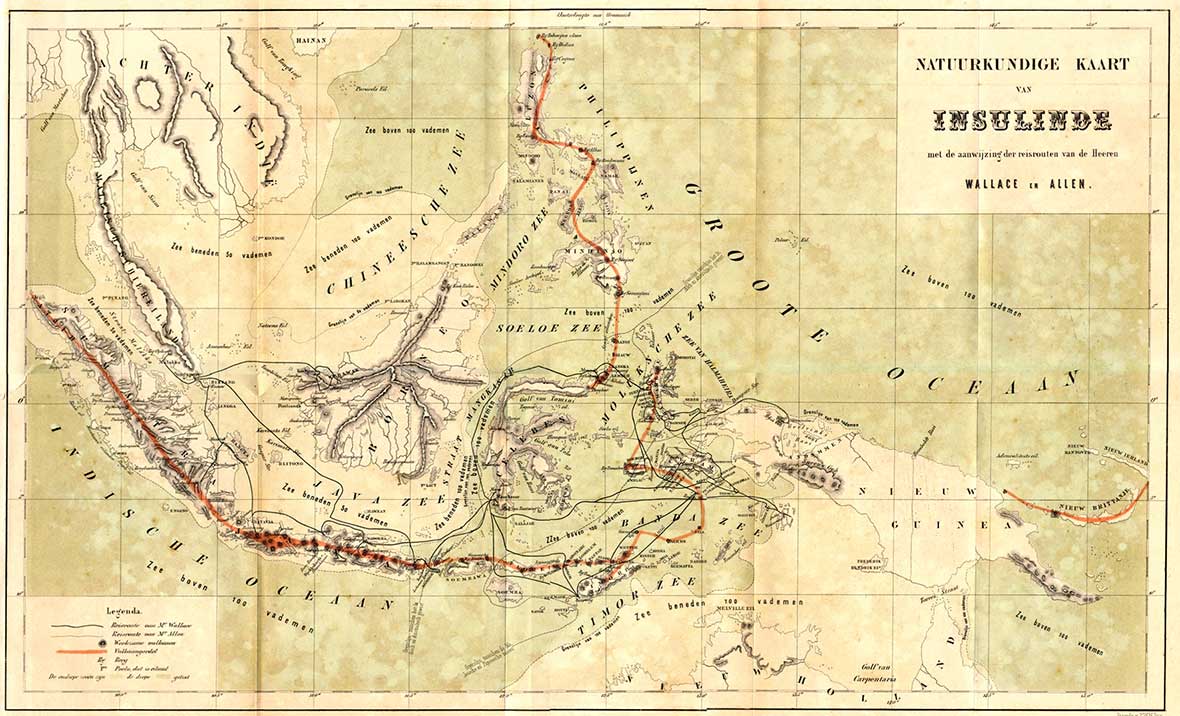

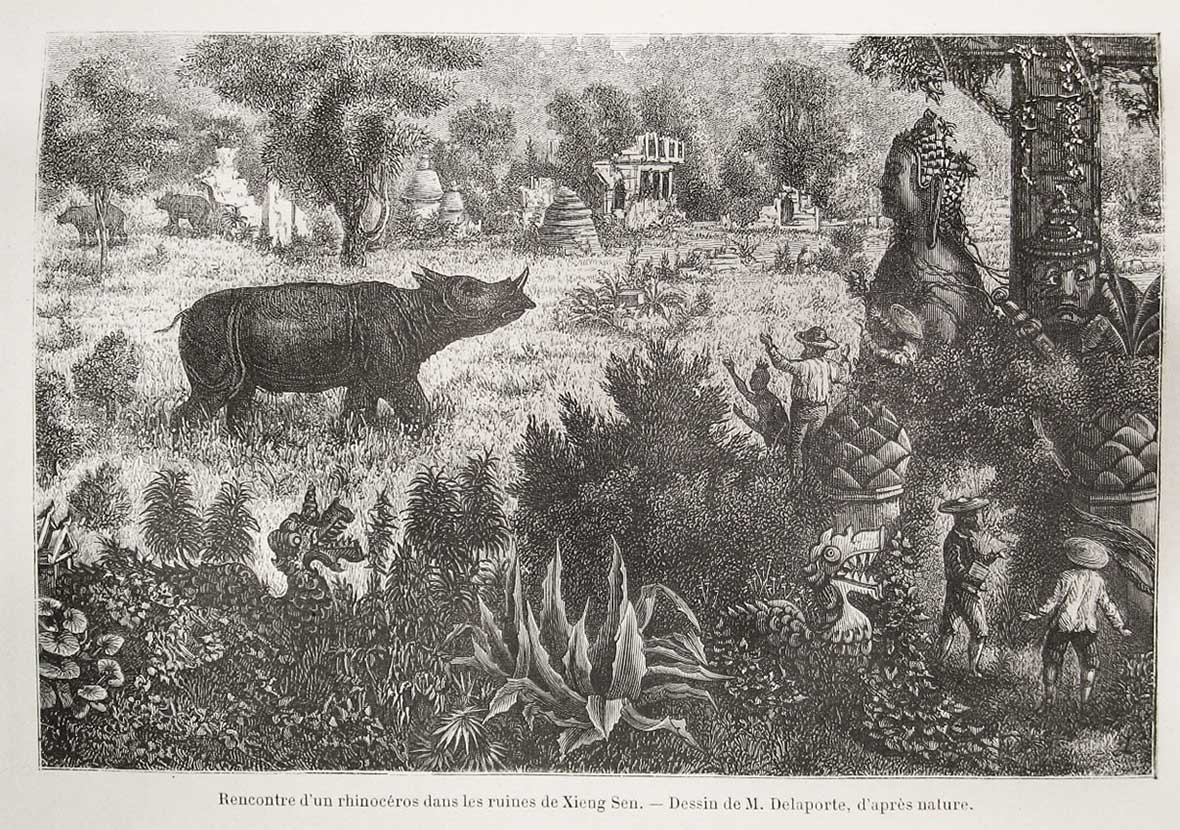

An all-time favorite Southeast Asia explorer story, this tracks the French expedition from Cambodia with Francis Garnier for a viable route via the Mekong to the riches of China. Unlike the other books on this list, this is a historical account, not a personal account. The story is just too big to waste it on one explorer’s opinions. Travels in Cambodia and Part of Laos: the Mekong Exploration Commission from Garnier is difficult to find in English and, well, Milton Osborne knocks it out of the park.

Spoiler alert, you can’t make your way from Cambodia to China on the Mekong (much to China’s modern dismay), but the story is a journey with excellent illustrations and tidbits and scope that’s left out of the personal accounts. On their way to the Middle Kingdom, the book provides genuine charm, adventure, and drama, mixing the power politics of the French expedition with the mysterious parts of Asia unknown to Westerners at the time.

This 19th century tale journeys through Cambodia and Laos, the group itself walking in the footsteps of the few great travelers who fought their way north. The explorers find themselves tracing the steps of Henri Mouhot himself after his death, and they, in an odd reunion, even find his dog.

The Golden Chersonese and the Way Thither, Isabella Bird

This would be the final expedition of Isabella Bird. Hers was not the path of a scientist or an adventurer, but that of a travel writer, the Golden Chersonese referring to the Malay Peninsula. Like so many, she starts out from Singapore and goes on a journey to the heart of the peninsula.

“Malacca fascinates me more and more daily. There is, among other things, a medievalism about it. The noise of the modern world reaches it only in the faintest echoes; its sleep is almost dreamless, its sensations seem to come out of books read in childhood,” she writes.

Perhaps one of the 19th century’s greatest female travel writers, Isabella Bird wandered the globe, well known for her works in Japan, America, and China, becoming a pioneer in the field of photography.

This, however, would be her final journey and one in which she’d honed her craft. In fact, upon reading, it seems strangely modern. The overuse of exclamation points and terse sentences might as well be on Twitter. Indeed, it’s not really a book at all, but a collection of letters written by Bird to her sister back in England, who would die of typhoid.

It’s also, well, happy and relaxed. Yes, there are bugs and disappointments, but Isabella Bird isn’t trying to impress a newspaper or find a flying frog. She just loves traveling.