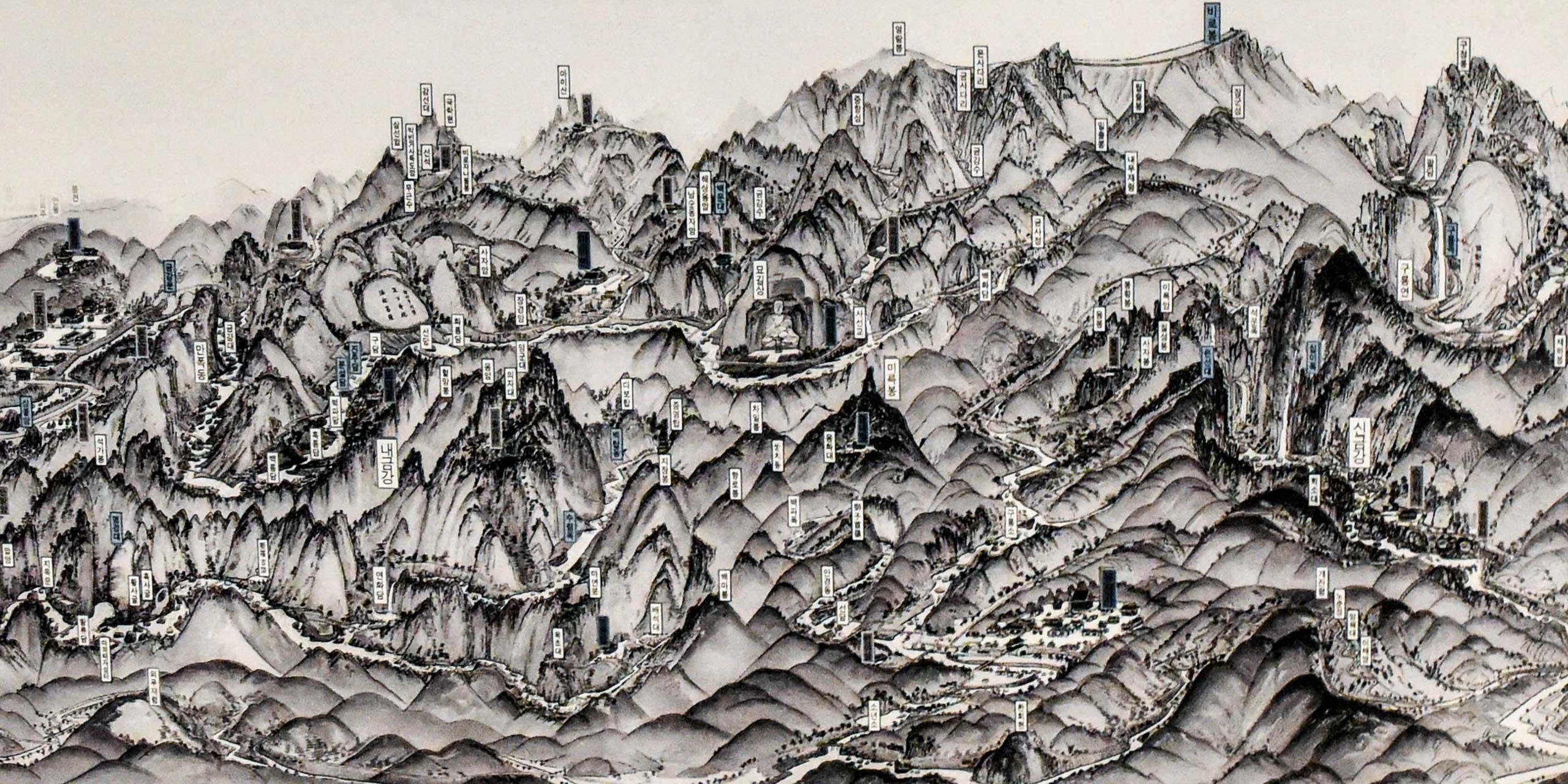

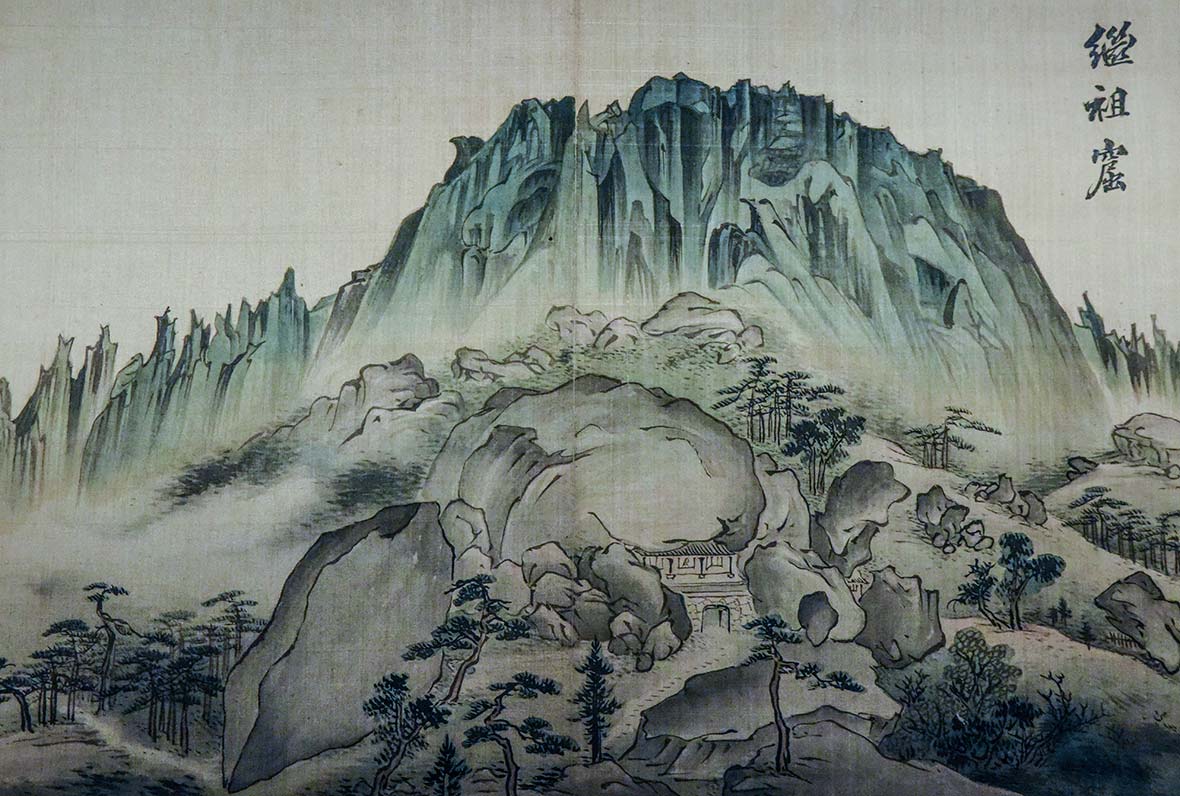

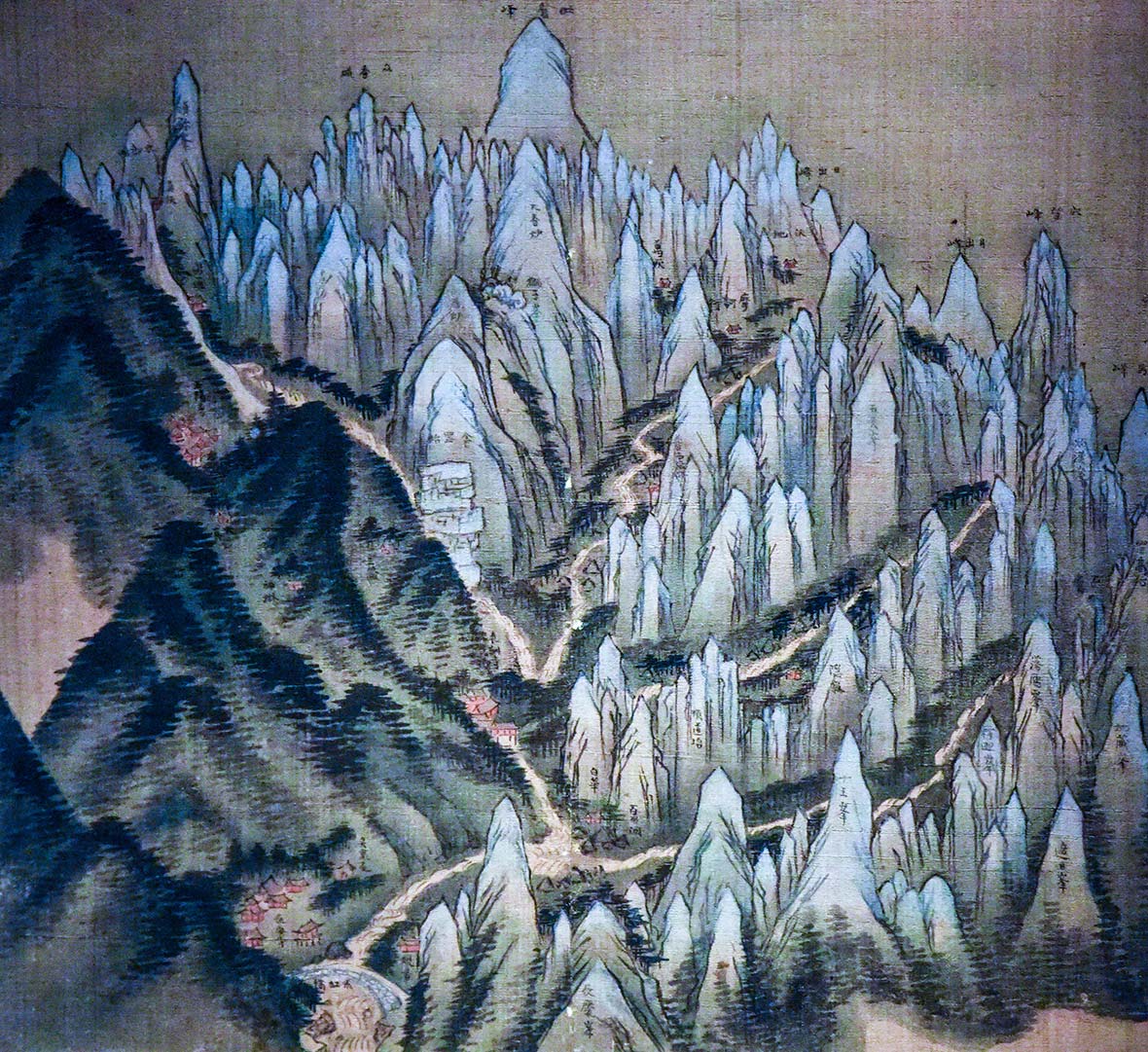

I imagine a warlord would have loved to possess this artwork. The painting before me in Seoul’s National Museum of Korea is majestic, depicting a panoramic alpine setting of forested peaks, curling rivers, and verdant valleys. It also displays, in minute detail, the infrastructure and layout of each settlement in this mountainous region.

I can study the path of roads, memorise the layout of towns, scrutinise the design of temples, and analyse the security of government compounds. Even the topography of these locations can be easily deciphered. This 300-year-old artwork offers the kind of birds-eye view, and blueprint to a region, that armed forces now secure via drone and satellite imagery.

Had it been unfurled in front of an 18th century warlord, he could have gleaned enough information to begin planning an invasion of these communities. Which is what made these Jingyeong Sansuhwa artworks revolutionary. Also known as true-view paintings, they emerged in the 1700s.

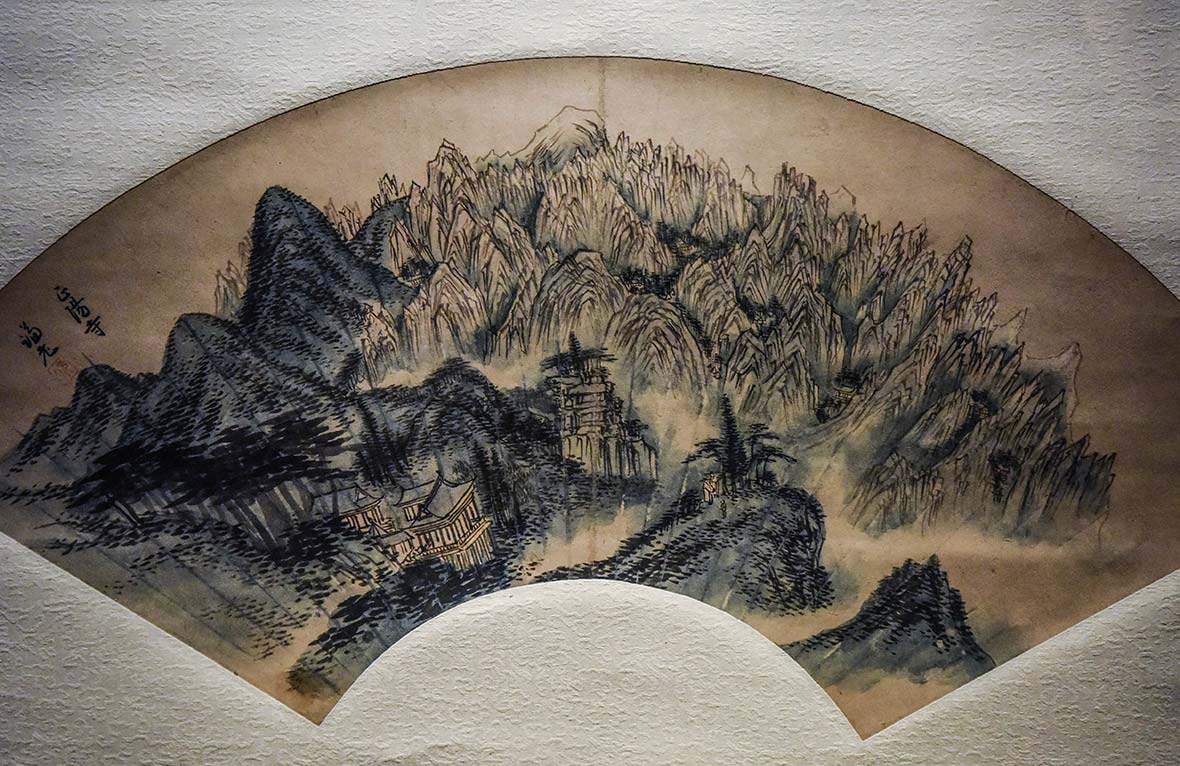

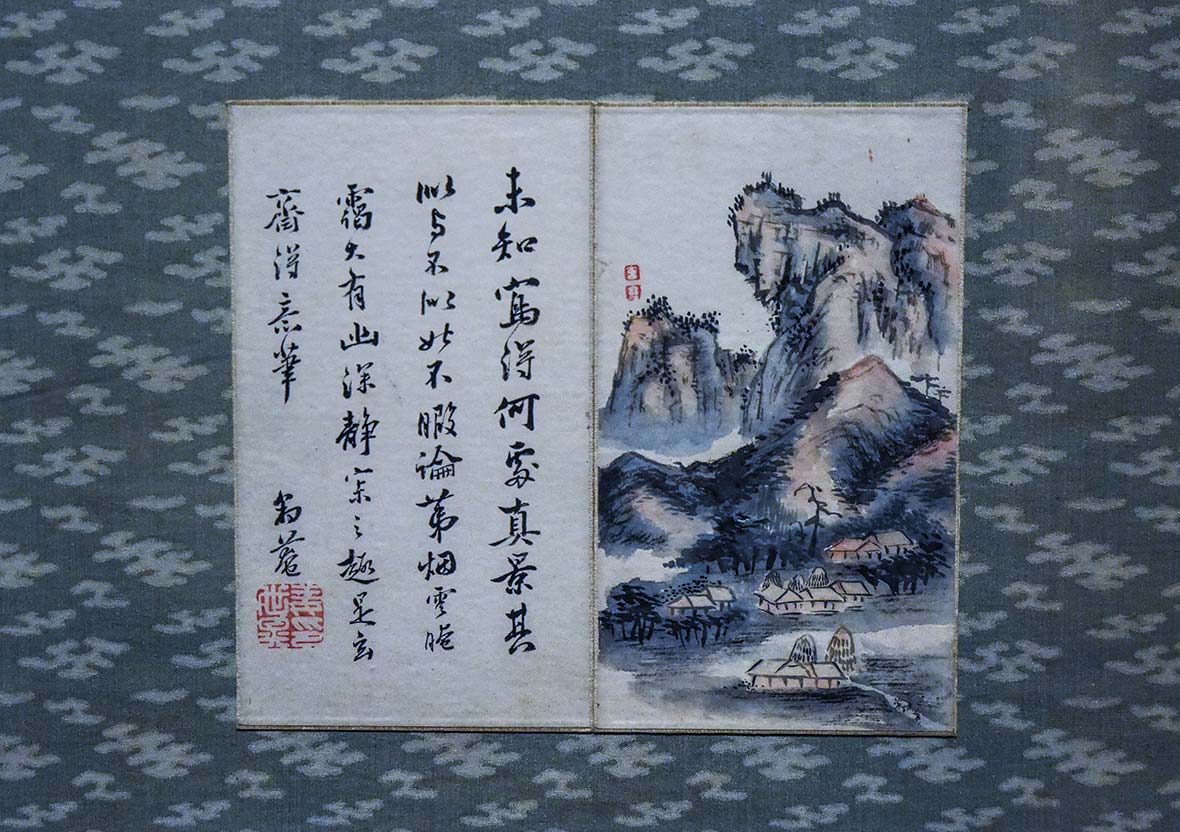

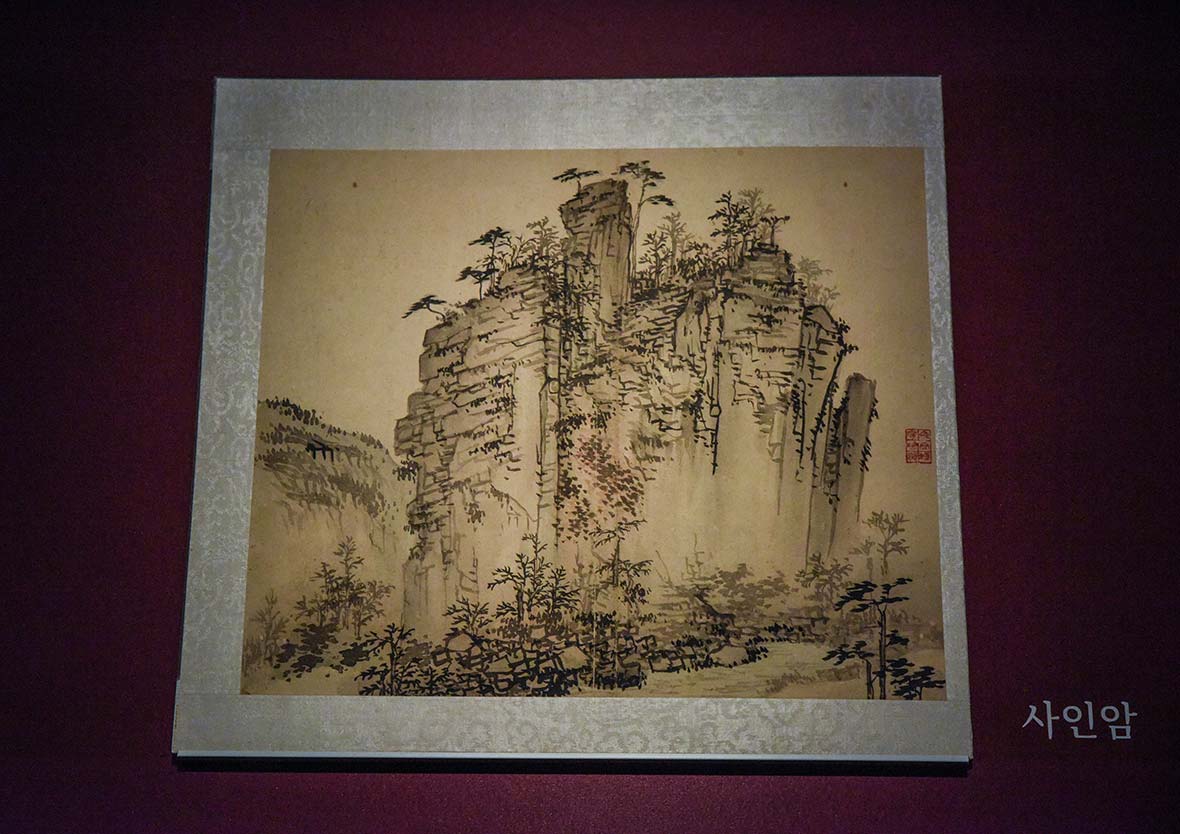

They were the creation of men who were part spy, part journalist, part mapmaker, part artist. These gifted fellows sat outdoors for hours at a time, meticulously drafting a complex interpretation of the locations before them, taking notes of what they witnessed.

Then they would return to their studios to paint the finished article. The art they have left behind is not just beautiful. These paintings are also valuable historical documents, offering insight into political, cultural, and architectural elements of Korea during the Joseon Dynasty period (1392-1910).

Prior to true-view, Korean art was dominated by landscapes. Paintings focused on mesmerising countryside, which often showed no sign of human existence. When people and their constructions were included, typically they were relegated to subtle details within a commanding natural environment.

I was unaware of Jingyeong Sansuhwa before I entered this phenomenal facility in the South Korean capital. A colossal and modern complex, housing more than 400,000 artefacts from prehistoric to modern, it brilliantly explains and showcases this nation’s cultural and artistic history. I absorbed exhibitions on Korean ceramics, calligraphy, lacquerware, woodwork, sculpture, furniture, bronzeware, and religious murals.

Then I found true-view. My vision was drawn to a group of regal men, donning loose Hanbok robes, the iconic form of dress worn in Korea for the past 1,500 years. With peaks and groves looming in the distance, they were gathered in a courtyard, where an Imperial ceremony took place.

To their left, a line of graceful women held flags aloft. To their right, musicians created an aural backdrop. In front of them, tables bulged with food, offerings, and flower arrangements. And inside the hall at the courtyard’s core, a red throne sat empty. Everyone was awaiting the arrival of the man would occupy it – the Emperor.

Thanks to the exquisite detail of this painting, I could sense the pageantry of this occasion. That realism proved widely appealing when true-view art first spread. In the 18th and 19th century, travel became popular among wealthy Koreans, who sought to see more of their beautiful lands.

This passion was indulged not just by taking vacations, but also by exploring with their minds. Travel literature began to sell strongly, as readers lapped up non-fiction accounts of journeys near and far. True-view also had a place within this burgeoning market.

Rather than giving an impression of famous Korean landscapes, it catalogued them. Jingyeong Sansuhwa artworks were like an artistic atlas, with some measuring up to 3m in length and portraying great acreage. Owners of such paintings could stare at them for hours, if they pleased. Each time they returned to this activity, they were liable to spot a fresh detail, to learn something new.

I was similarly captivated. Although I greatly appreciate paintings, few secure my attention for more than a minute or so, even the coveted works of the Old Masters I’ve been lucky enough to see in museums across Europe. Not so with true-view.

I found myself, for example, trying to decode the layout of an ancient Korean fort, aiming to understand how it was designed to repel different forms of attack. Then for a while, I got lost on a path that curved through intricately depicted forest behind the fort.

Unless time travel becomes reality, these paintings are perhaps as close as I can get to immersing myself, visually, in Korea of the 1700s. In fact, next time I return to Seoul I must buy a reproduction of one of these artworks. I may not be a warlord, but I’d love to possess a true-view painting.