More than 1,700 years ago, skin disease helped inspire a kingdom. In Nepal’s Kathmandu Valley, beneath the Himalayan peaks, a young farmer skulked through verdant fields. He tended to crops in isolation, keen to hide his disfigured face from intrigued gazes.

One steamy day, this tired worker reached the Bagmati River, which flows from the hills north of Kathmandu, south through the valley and on into India. Bending down, he wiped his brow with water. The farmer was unaware this is a sacred river which hosts Hindu temples and ritual cremations to this day due to its mythical powers to cleanse the spirit.

This simple act of refreshment triggered a miracle. Yet the farmer did not realise until he finally encountered other people. Rather than recoiling at the sight of him, as he expected, they smiled and complemented his appearance. The Bagmati water had cured his condition.

News of this magical makeover soon reached Nepalese King Biradeva, who named the farmer Lalit, which meant “handsome”. The king then had a divine dream that he should build a grand new city on the banks of this powerful river. He did just that, at the end of the 3rd century, and called it Lalitpur. It soon became the hub of a powerful Nepalese state.

This unique origin tale absorbed me when I arrived at the entrance to Lalitpur, more commonly known as Patan, and read it on an official brochure handed to tourists. I’m glad I took that booklet, as I’ve not been able to find a detailed account of this legend online. It is little known outside of Nepal, just like the place to which it pertains.

From a tourism perspective, Patan is greatly overlooked. It is among Nepal’s oldest cities, and is believed to have acted as the capital of the country’s Licchavi, Thakuri, and Malla dynasties. Before Bhaktapur or Kathmandu made their mark, Patan was already a commanding city that helped establish cultural and artistic traditions which shape Nepal to this day.

Yet now Patan is obscured by the long shadows of its renowned neighbours within the Kathmandu Valley: Kathmandu and Bhaktapur. The former is the national capital, by far Nepal’s largest city, and the gateway to this majestic country, as the location for its main international airport. Once tourists have explored the temples, heritage architecture, and markets of Kathmandu, most make for the mountains.

Those who seek further urban delights tend to pick Bhaktapur. Situated at the eastern end of the valley, this was once a capital of the Malla Kingdom. Now Bhaktapur is renowned for the array of beautiful timber-framed buildings that line its historic heart. Tourists flow through this warren of timeworn streets to admire its artisan museums and distinctive Palace of 55 Windows.

By comparison, I encountered few foreigners in Patan, despite its generous appeal. There, in the valley’s south, dozens of temples, monasteries and a unique palace are arranged in the shape of a Buddhist symbol with cosmic powers. That aforementioned booklet taught me the city’s layout is modelled on the Dharmachakra, or Buddhist Wheel of Law.

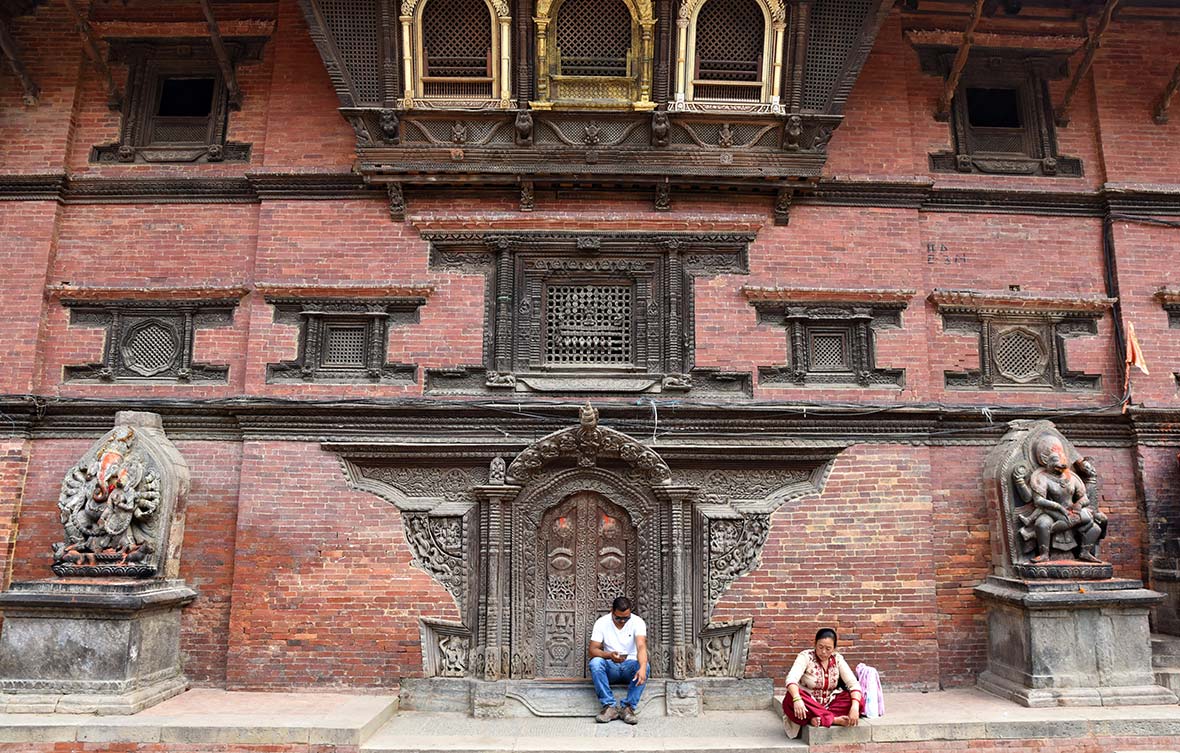

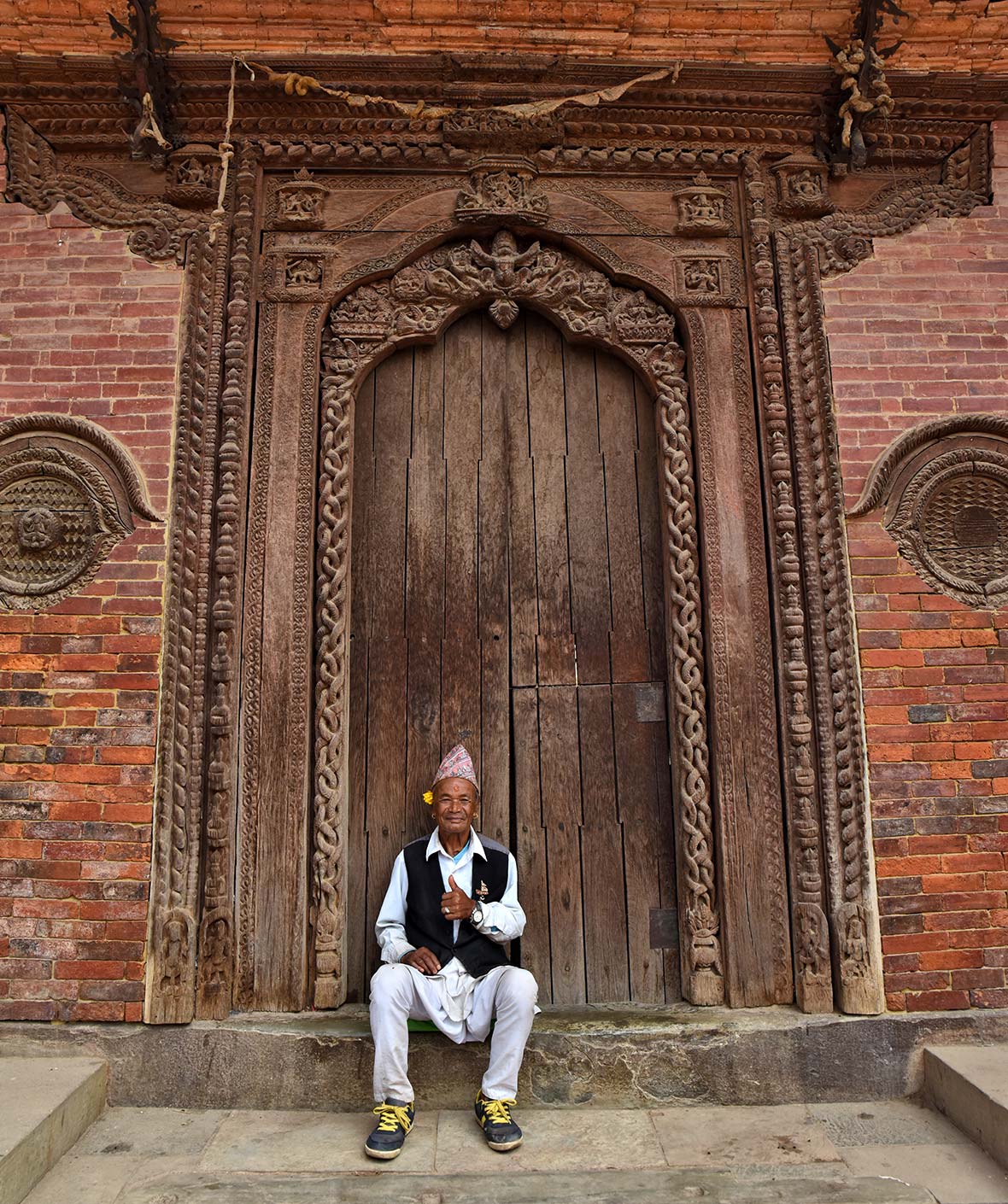

Patan’s appearance has barely changed in centuries in its Old Town area, which surrounds the hub of Patan Durbar Square, a UNESCO World Heritage site. This area brims with religious complexes, historic monuments and artisan workshops. Patan is known for its abundance of gifted traditional craftspeople, who specialise in the woodwork, stonemasonry and mural painting that beautifies its heritage structures.

Durbar Square was once the core of Patan’s Royal palace. I found I was free to wander through many of its finest remains. Tourists gathered to photograph the 21 golden spires of Krishna Temple, a sublime Hindu complex made of stone that dates back almost 400 years.

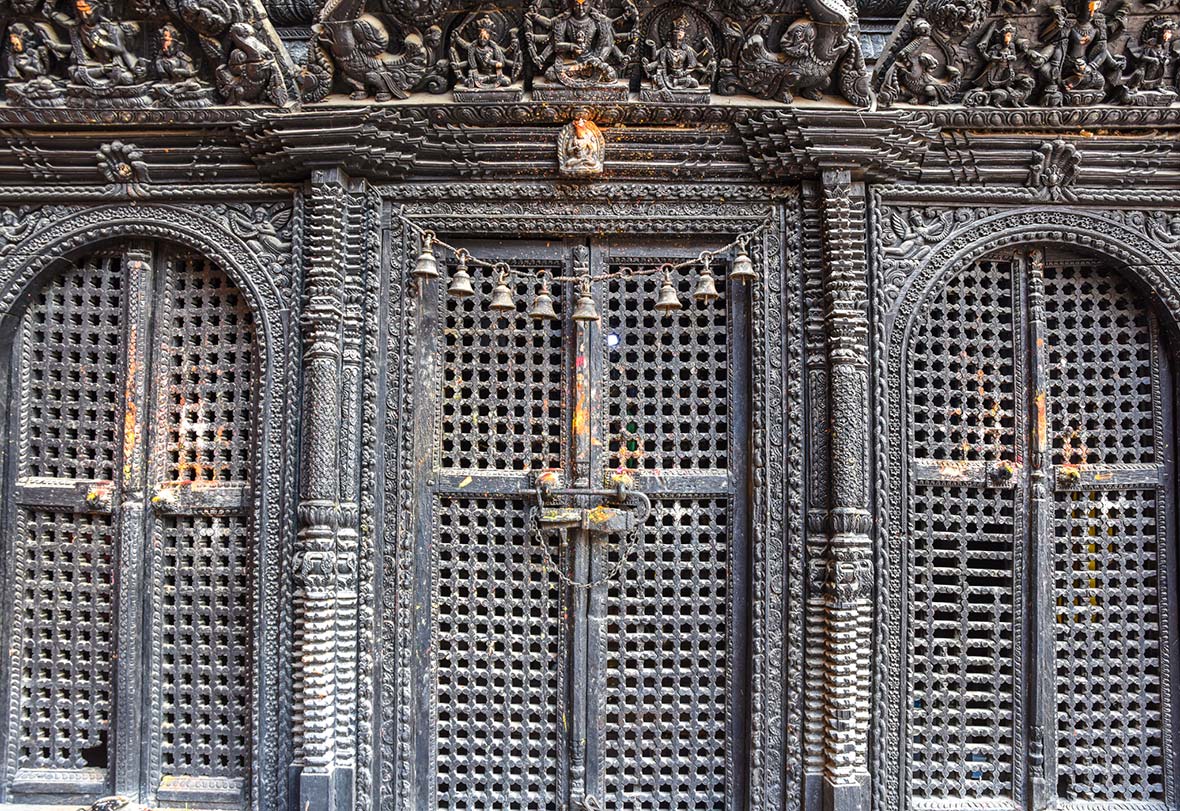

About twice as old, the nearby Golden Temple is a tall shrine with intricate wood carvings, delicate repoussé metalwork, and focused around an image of Buddha in its central courtyard. Kumbheshwar Temple, meanwhile, is the tallest pagoda in the city. It rises five stories, and hosts a sacred natural spring where worshippers bath during annual festivals.

Then there’s the sublime Mahabouddha. This temple is embellished by magnificent terracotta tiles, which collectively boast thousands of depictions of Buddha. That holy lord is honoured by a quartet of stupas believed to be more than 2,200 years old, which mark the east, west, north and south borders of Patan’s Old Town.

Visitors can also see the impressive home of Patan’s Kumari, one of Nepal’s living child goddesses. These young girls are worshipped as part of a millennia-old aspect of local Hindu and Buddhist culture. The Kumari is paraded through Patan each September, during the Indra Jatra festival, a huge, photogenic event that unfolds across the valley.

Most tourists who attend that festival do so in Kathmandu or Bhaktapur. Those who instead choose Patan, at any time of year in fact, are rewarded with the fascinating remains of a kingdom that once ruled this region and continues to sparkle, albeit in relative anonymity.