Muay Thai is everywhere in Thailand. From Chiang Mai to Phuket, it is one of the most popular sports in Southeast Asia. A favorite for visitors, be it from a luxury air conditioned box or a sweaty ringside seat, a Muay Thai match or lesson is a must for fight fans in the Kingdom.

It is also a relatively traditional practice — the rubbing of the nakmuay, the delicate wai ku dance around the stadium, the wai to the audience. Many first-timers are surprised to find Thai boxing to be so utterly different.

In Thailand’s long and storied Muay Thai history, one curious event sticks out in dry accounts of the early days of Rama I, a humorous fight that, in retrospect, seems to make so much sense.

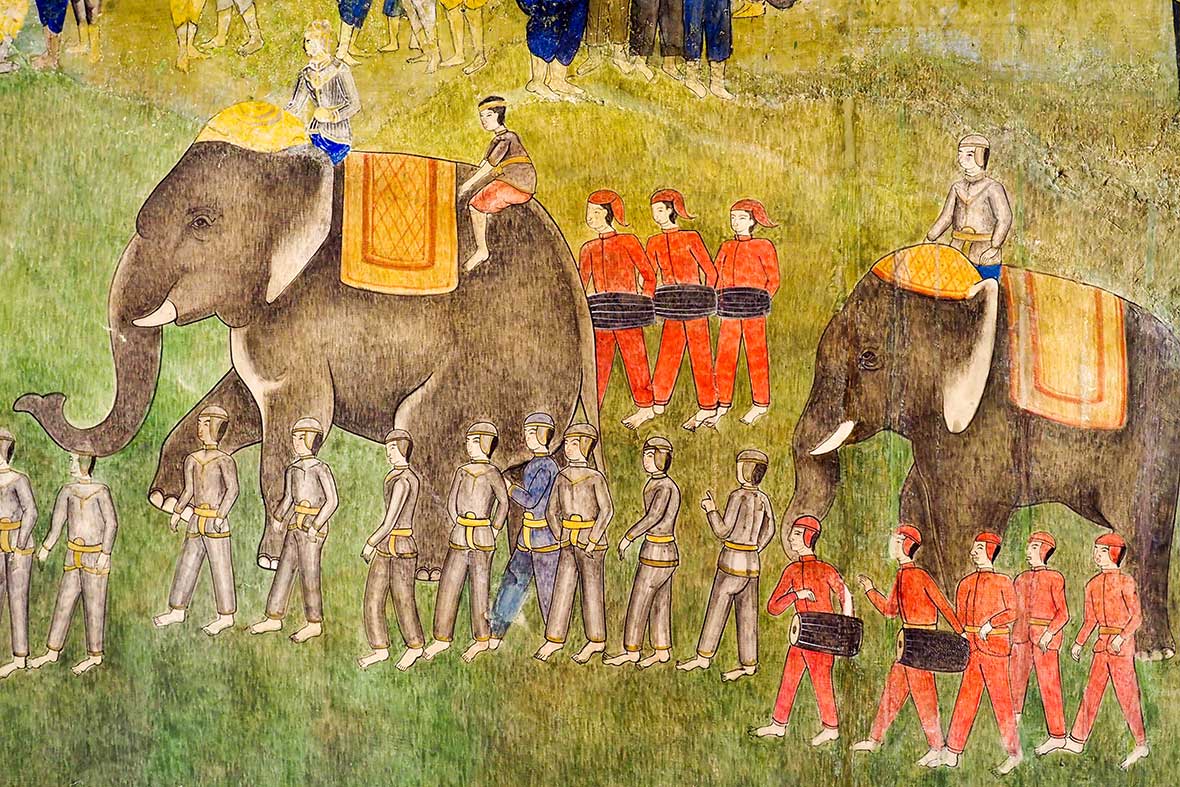

In the 1790s, Thailand was recovering from the sacking of Ayutthaya. After 417 years, the Burmese fell on the seat of Thai power in a battle that lives large in Thai history, and it wasn’t until 1782 that Bangkok became the capital.

The city found itself at the front of foreign trade with Americans, Dutch, French, and every other ship that happened to sail up the Chaophraya. Hard as it may be to believe, some of the structures that are tourist attractions today were standing back then, such as the case of Wat Arun, the Temple of Dawn, built in the 17th century. The Grand Palace, too, was standing as early as 1782. The Wat Traimit Temple in Chinatown had already been around for hundreds of years.

Bangkok was ascendant, with the Chinese emperor recently recognizing Rama I as the true king of Siam. Into this waded one particular French ship chronicled in The Dynastic Chronicles Bangkok Era, The First Reign and by German Klaus Wenk’s The Restoration of Thailand Under Rama I, 1782-1809.

In summation in BJ Terwiel’s Thailand’s Political History, an excellent read, an excerpt reads, “The captain’s younger brother was a pugilist of some renown and sent to challenge the Siamese by way of the Krom Phraklang (a government minister).”

Wenk’s account claims that this request was relayed to His Majesty King Rama himself, who would then go on to discuss it with his ministers.

“The King consented, on the advice of the Maha Uparat, as it was thought that otherwise one would be exposed to the charge of cowardice,” Wenk wrote more than 200 years ago. “Fifty chang of silver were set aside as the prize for the winner.”

The sum of 50 chang was 4,000 baht, a rather large amount at the time. The revered Maha Uparat, according to Wenk’s account, “personally supervised” the details of the match.

Prior to the match, the Thai fighter was rubbed down with oil and herbs. This is quite common to see at a Muay Thai match, before, after, and between rounds.

As accounted by BJ Terwiel, “In the fight, the Frenchman apparently tried to close in on the Siamese boxer, but the latter, in accordance with the Siamese rules, kept out of his reach, occasionally darting forward to deliver a blow and jumping back whenever the Frenchman moved forwards.”

To fans of Muay Thai, this is all-too obvious. The rules can vary and have over the years, but even today it’s not uncommon for an entire round to go by where boxers simply ride each other around the ring, calmly checking reflexes while barely making contact, perhaps a little taunting from the unsportsmanlike. The fighting style is said to have originated in the 16th century with the use of short weapons in the Thai military.

Less is known about French boxing style of the 18th century, and savate, also called chausson, wouldn’t exist for a few more decades. Bare-knuckle fights were all the rage in Britain, even gracing the Royal Theatre; accounts, however, seem to agree that it was hardly a graceful affair.

Accounts differ on the cause of the Europeans’ dissatisfaction. Wenk relates that it was the slipperiness of the oil used on the Thai fighter that caused the frustration, but this is not mentioned in the Dynastic Chronicles.

“The Europeans were not familiar with this light-footed technique, and impatiently the captain leapt into the ring and seized the Siamese in order to force him to ‘give battle’,” Terwiel relates.

At this, the uparat could not let this offense stand; Maha Uparat mentioned herein was the highest office in the land, second only to the king himself. The “Grand Viceroy” himself entered the royal rumble and brought the French captain down with a kick.

In the words of Terwiel, “General pandemonium broke out.”

The brothers were so terribly beaten that it necessitated carrying them back to their ship on the Chaophraya. Mercifully, King Rama sent them medical aid, but the ship decided it had had enough Muay Thai and after the brothers recovered they left Bangkok for good.

Gambling, violence, a grand minister kicking an arrogant European in the face, and the mercy of a mighty king — what more could a story need.

Much has changed in the last few hundred years. In the shops of Bangkok today, visitors find brightly-colored Muay Thai shorts for sale. Tattoos and knick-knacks abound. After matches, bleeding athletes – male and female – pose for photos.

There are many classes — some at fine hotels — at which one might be instructed in the delicate art of Muay Thai today, and many hopeful fighters come from around the world to train in Bangkok. But YouTube abounds with drunken tourists in Thailand who fancy their chances with a Muay Thai boxer; it never, ever ends well.