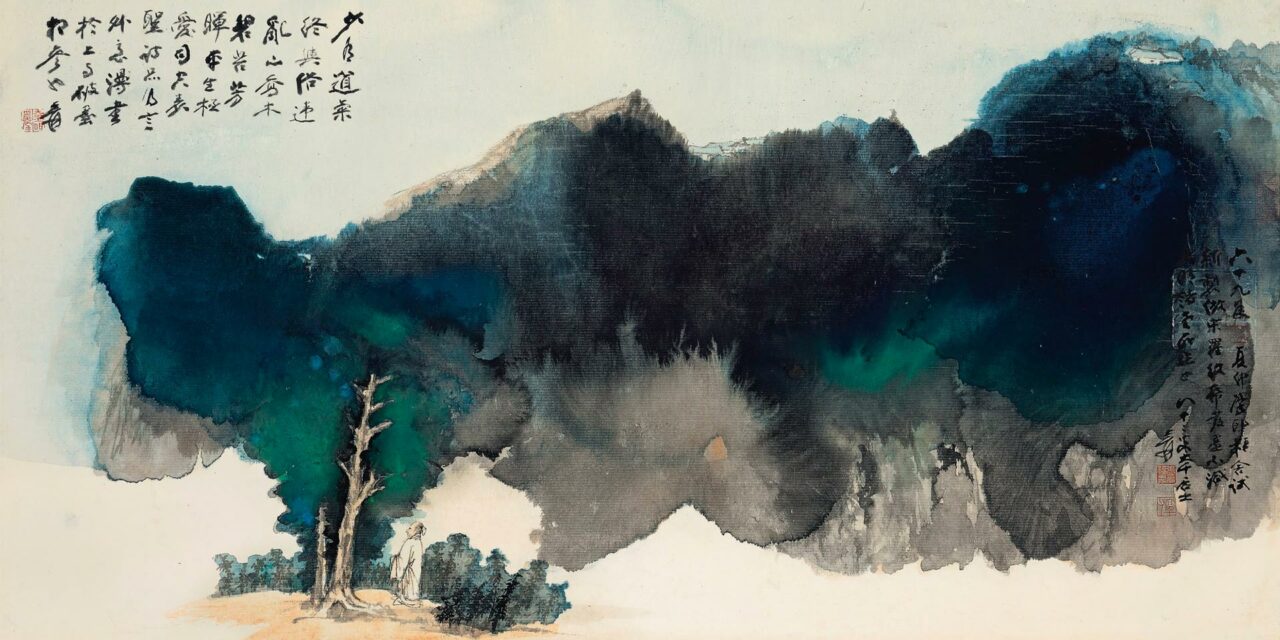

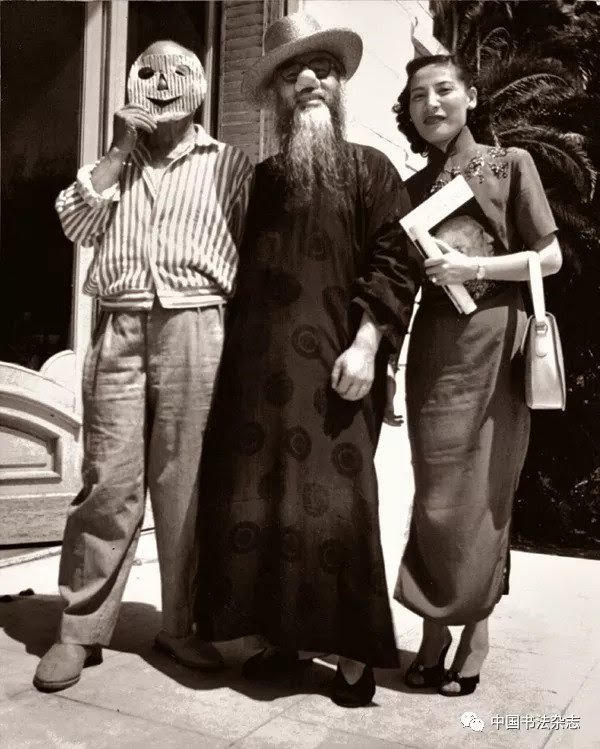

In the spacious sitting room of this landmark house at the outskirts of Taipei hangs a photo from 1956 of two painters posed in the garden of the Masse d’art Moderne in France; newspapers worldwide heralded this as a meeting of genius from the East and West. Pablo Picasso, the western genius was perhaps the most famous living artist in the world and at the top of his powers as both creator and personality but his accomplishments would never match Chang Dai-chien, or Zhang Daqian to the mainland.

“He was a kind of prophet, a prophet and seer. There was something otherworldly about the way he worked,” says Ken, a former student who volunteers at the residence. Chang Dai-chien was all of these and his house belies his complicated personality. The wisdom of ancient China captured in his work under the same roof as his modern self indulgences, best epitomized by his emerald green Lincoln Continental on view in the house’s tiny garage.

ABOVE: Unassuming Residence of Chang Dai-chien.

Chang Dai-chien lived a life of scholarship and hard work but also of adventure, guided by patriotism and fortune. Recognized as a protege at a young age due to the quality of his calligraphy, by the age of twenty Chang had served as a monk and traveled from China to India and Japan to study different painting and dying techniques. During his youth he was kidnapped and held for ransom by a bandit warlord who then kept him on as secretary because he loved the quality of his brush work.

As a nationalist he was Chiang Kai-shek’s art advisor during China’s Civil War and was instrumental in moving much of what makes up Taiwan’s National Palace museum collection off the mainland and out of harm’s way. It was during that period that he took his family on a world wide exploration funded by the sale of his own works (and even more so from forgeries of the great masters of Chinese painting) to major museums in the west.

Chang built a palatial estate outside of Sao Palo in Brazil where he lived for fifteen years before setting up in Carmel, California. In 1978, at the age of 78 he told a friend “This should be the time for the old leaf to fall at the root of the mother tree.” Thus he returned to Taiwan and began the three year construction of Mo Yieh Ching Shih, his garden home retreat built along the babbling Waishung brook on the outskirts of the capital city.

ABOVE: Chang’s green Lincoln Continental.

Chang designed each part the two story quadrangle home and gardens that would occupy 500 ping or 18,000 sq ft of property he purchased personally to support his two main occupations; painting and entertaining. After his death family members donated the property to the National Palace Museum which manages it as Chang Dai-chien Memorial Hall and allows weekend visits by special request.

Entering through the modest entrance gates which lead into the homes garden visitors are greeted by a meticulously landscaped carp pool where a contingent of fat, old fish splash around in flashes of gold and white.

“The pond is a place the artist visited everyday, seeking one fish in particular which he called his old bearded fellow, and he would spend some time talking to the fish, this is part of Chang’s belief that he himself was close to the animal world and would in fact be reincarnated as a black ape,” Wendy Mao tells me during my tour of the home.

Chang spent as much time in his garden as he did in the studio, constantly reorganizing its elements. whether it was the pots of tiny bonsai trees that line the terrace or the huge boulders that make up the “plum Hillock” where his remains are buried.

ABOVE: Entrance to the Chang residence.

The house sits just as it was when the master still occupied it, down to a clock which is stopped forever at 8:15, the minute of his final breath. Each room is a balance of utility and the artist’s eclectic tastes. The living room is lined with high french windows looking out onto the gardens and decorated with medals and honors from governments around the world. The walls are hung with paintings by Chang’s brother and mother, both accomplished artists, as well as photos with friends and colleagues, including that famous snap of he and Picasso shaking hands in 1956.

Entering the high ceilinged, spacious studio is a shock. For among the almost comically oversized brushes, sitting at the long worktable is the man himself, frozen forever in mid stroke and overseen by his favorite gibbon which seems to approve the work in it’s taxidermied state. The wax figure, almost too realistic, is protected from guests by a velvet rope but the rest of the room invites interaction as the artists tools are scattered about the table and hung in racks open to fondling fingers and curious gazes.

Through the houses guest rooms a hall leads to the dining room where a table for eight was laid twice a day. Chang was an ardent gourmand who kept and trained chefs to serve his favorite Schezwan style foods to friends and visitors daily. “The master had a wide circle of acquaintances, hoodlums, gangsters, businessmen, politicians – a retinue of courtesans and always poor art students were here for long meals and discussion every day” Comments Mao as she shows off some of his hand lettered menus.

A stairway from the work room leads to a second floor studio where Chang would retire when he needed to fully concentrate away from the constant traffic that came and went. It was also here that Chang oversaw the mounting and framing of his work, something he took very seriously. The windows of this more intimate studio look over the expanse of the houses gardens where from that vantage the designs taken from the pantheon of Chinese painting can be appreciated. It’s also where he himself would wander and pose for photos in his sages robes with walking stick, stroking his flowing beard like some ancient holy man reborn into the modern world.

Chang died of what his daughter calls an exhausted heart in 1983. His body was cremated and his ashes entombed beneath the largest boulder in his garden, a rock that resembles the outline of Taiwan which is named Mei Chiu meaning plum hillock, written here in the master’s own hand. My guide has pointed out though that there is a single but important brush stroke left out. This she says was an intentional exception to show respect as the translation plum hillock can be a reference to Confucius, but it was also an honorary name his students gave him, a last little joke by the great scholar to remind us he was a prankster as well.

This is the legacy of the great Chang Dai-chien: prophet and populist, jester and scholar, dilettante and possible ape.