He was the size of a Sumo and had the skills of a warrior and the influence of a senior politician. In the 1860s, he helped overhaul Japan’s fractured political system, founded its modern nation, and set it on course to become a united, global powerhouse. His name was Saigo Takamori, the “Last Samurai”.

He inspired not just change, but also the 2003 Hollywood blockbuster, The Last Samurai, starring Tom Cruise. That movie borrowed liberally from the tale of how Saigo’s lethal prowess in battle saw him rise through the samurai ranks to become perhaps the most influential warrior in Japan.

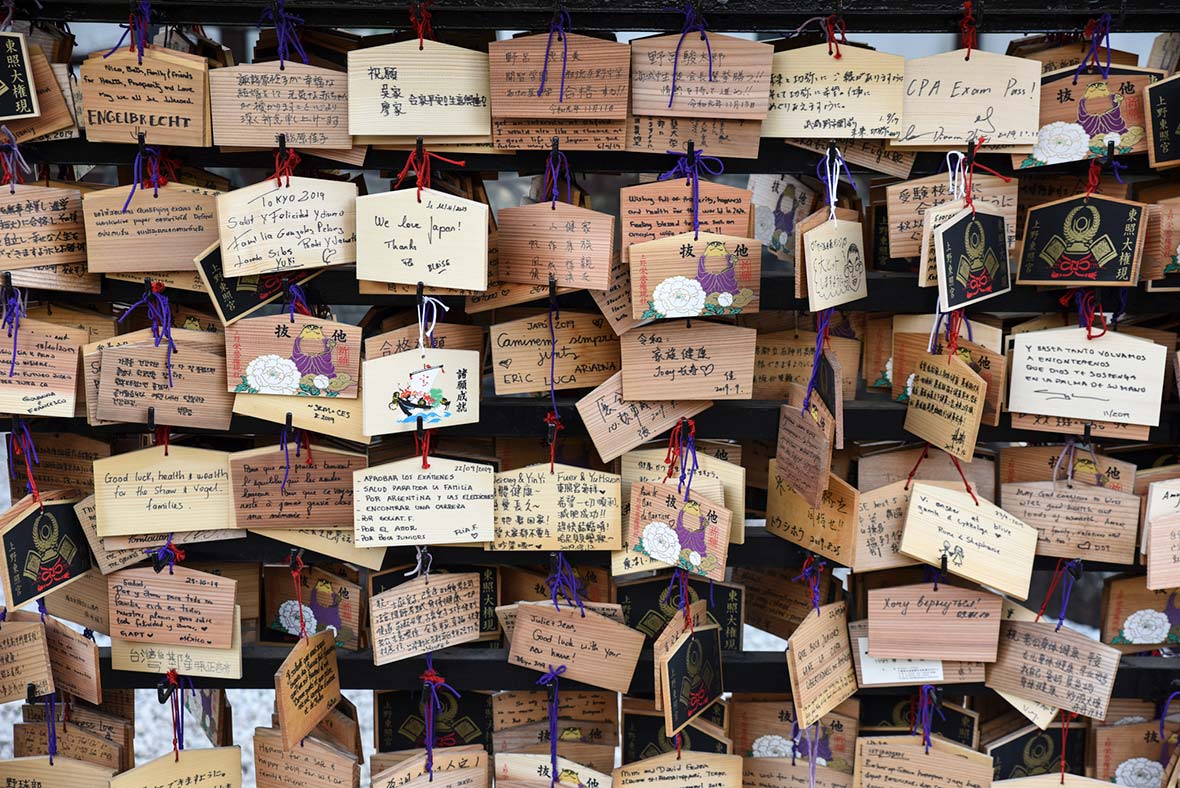

If you’ve ever visited this country, you may well have passed locations he shaped, or even sighted this extraordinary figure. Because there are monuments and museums to Saigo across the country. Most prominently, he looms large over one of Tokyo’s finest attractions, Ueno Park, a large green space with a 12-foot-tall bronze statue of the samurai at its southern entrance.

As much as his imposing size, what snared my attention as I wandered this serene park was the dog by his side. Saigo is depicted in a kimono walking with Tsun, his beloved pet, with whom he is also shown in numerous other artworks. This is one of many sites across Japan where tourists can encounter this samurai. The Saigo Takamori Residential Site Museum, in the small city of Nobeoka in southern Japan, displays military artifacts connected to him.

Some 400 miles south of there, the Saigo Takamori Southern Islands Museum explains the samurai’s three years in exile here. The larger Saigo Nanshu Memorial Museum, meanwhile, offers the most comprehensive insight into Saigo’s personal life, accomplishments, and legacy. That modern facility is located near a 25-foot-tall statue of Saigo in downtown Kagoshima. This southern city is where the samurai was born in 1828 and met his demise five decades later.

But before we delve into the end of his story, let’s head back to its beginning. Despite being from a relatively humble family—his male relatives were low-level samurai—Saigo stood out due to his uncommon height and heft. He was six feet tall and 200 lbs in weight.

That was enormous during an era when many Japanese men measured less than 5’4 and 140 lbs. His size and strength made him an enticing prospect as a warrior. This potential was not lost on his family, who pushed him to train diligently as a samurai. He progressed swiftly.

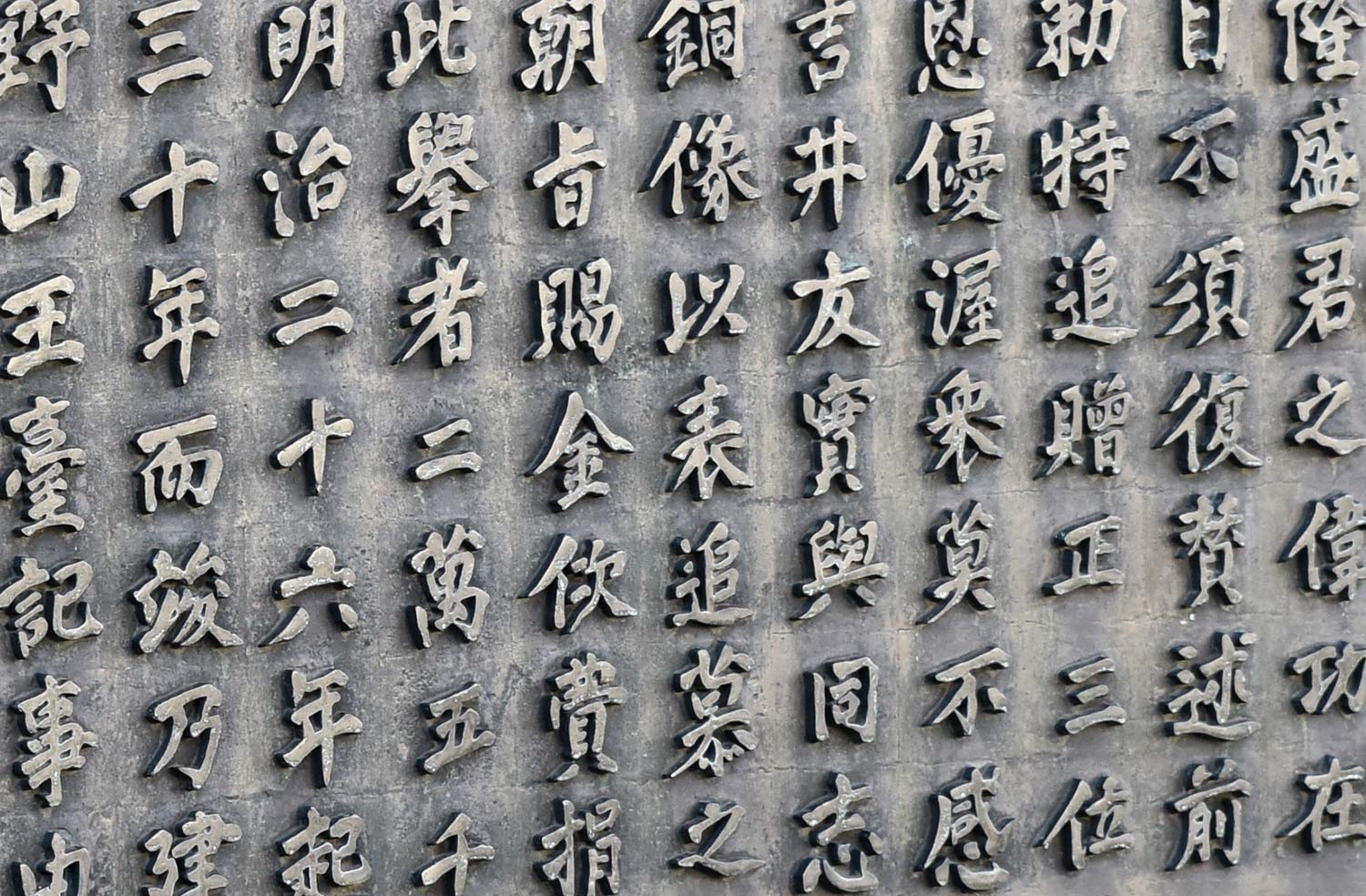

Being a samurai was a noble pursuit. These warriors had been powerful in Japan since the 1100s when the country moved from being controlled by an aristocracy to having Governments influenced by wealthy feudal lords and elite samurai.

Those warriors were not just fierce but also cultured. They introduced lasting elements of Japanese culture like Ikebana flower art and tea ceremonies. When necessary, though, a samurai like Saigo could slice through foes at will. This intimidation factor, combined with his tactical prowess and natural leadership attributes, helped him become the commander of an elite Samurai force in Kyoto, the Imperial capital, by his mid-30s.

As he reached 40, Saigo’s years of preparation met opportunity. Japan was about to experience a seismic shift, and he was standing astride the fault line. In January of 1868, Saigo led a unit of warriors that invaded the Edo Palace in Tokyo, a stronghold of the country’s Shogunate military Government.

This was one of the most symbolic acts of a famous coup, now called the Meiji Restoration. It marked the shift from Shogunate to Imperial rule and saw Japan fuse its ancient traditions with Western military and industrialization strategies to become a global heavyweight.

In recognition of his key role, Saigo was awarded the highest honor by Japan’s new monarch, Emperor Meiji. He then briefly retired. Before in 1871, he was coaxed back into the fray with the responsibility of commanding 10,000 troops as the head of the new Imperial Guard. This unit helped quell political dissent and vanish the emperor’s military foes.

Yet Saigo’s legacy is more complicated than that of a warrior hero. He later fell out with his Imperial superiors and returned to his home city, Kagoshima. There he opened a school that gave samurais advanced military and physical training.

This academy grew so huge, guiding thousands of warriors, that it became viewed as a threat by the Government, which had been plagued by samurai insurgencies in other parts of the country. In 1877, Saigo’s men fought and lost to Imperial forces.

His final act on earth was one forever associated with Samurai pride. In defeat, they would choose an honorable death of seppuku, the ritual suicide of plunging a sword into their torso. Saigo was not without flaws or failures. Nonetheless, he died a legend. His fingerprints remain all over Japan, where tourists can view his monuments, peruse his museums, and visit the sites where his daring and skill altered the country.