WRITTEN BY

Nazima and Earl Kowall

PUBLISHED ON

November 9, 2017

LOCATION

Bhutan

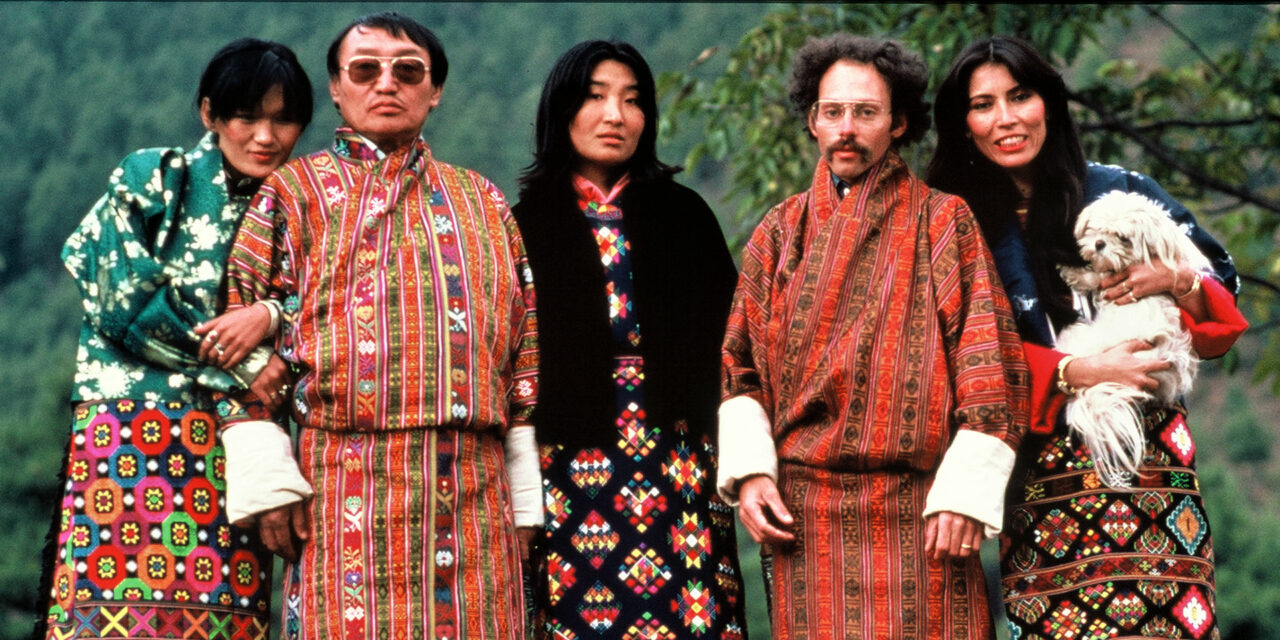

On a beautiful day in Thimphu, Bhutan’s capital city, my family friends Lyonpo Sangey Pinjore, Chief Justice of Bhutan and father-in-law of eldest princess Sonam Wangchuck, and his daughter and niece, both called Chimmi, requested that Earl and I don traditional Bhutanese dress and take a group portrait in the garden of his house.

Longpo Sangey arranged special permission so that Earl and I could experience aspects of Bhutanese life not available to the average tourist. We were able to see Bhutan in a way few others ever do.

ABOVE: Nazima and Earl Kowall in Bhutan.

Earl and Lyonpo both wore a gho with a white shirt inside with sleeves folded into a cuff and embroidered Tibetan boots. If Lyonpo had gone to his office he would have put on a kabney to denote his rank, a long, raw silk orange scarf running from his left shoulder to his right hip. The two Chimmis and I, holding a cute Lhasa apso dog, had on kiras topped by silk brocade toegos, or jackets, worn over long-sleeved silk wonjus (blouses). The fabric of each gho and kira, made of cotton, had different geometric designs handwoven on a back strap loom, a time-consuming craft where two inches of fabric can take 10 to 12 hours a day to complete.

ABOVE: Traditional weaving is difficult and time consuming, but the results are fascinating.

Among the lesser known pleasures of Bhutan, Earl was invited by the Kagyudpa monks of Phajoding Monastery to bathe with them in a primitive jacuzzi tub. After heating large stones in a charcoal fire, the monks plunged them into the large wooden tub with a pair of giant tongs. When the chest-high water had absorbed the stones’ heat, Earl and the monks jumped in, but the tub, exposed to the chilly elements, quickly cooled.

ABOVE: Young monks walk together in Bhutan.

Nevertheless, as Earl told me later, the jolly monks, who rarely bathed, were like animated children and their contagious joy made up for any discomfort.

In the capital Thimpu, we took to the golf links at the Royal Thimphu Golf Club surrounding the monastic fortress of Tashichho Dzong, the seat of Bhutan’s government and the king’s throne room. The greens were made of black tar, the grass was mowed by grazing goats, chortens ( stupas), and cows and stray dogs were some of the hazards.

The barefoot caddy in local dress told us that if we hit a goat, we would score a hole-in-one. In Bumthang, Limpo Sangey’s hometown, we fly-fished for trout in the Chamkhar Chhu. Many of our nights were spent at house parties, with Earl bashing away at the only drum set in Bhutan while I danced with my high-ranking Bhutanese friends.

One of the highlights of our Bhutan travels was our two-week horse and yak-packing, high-altitude alpine trek to the base of sacred Mount Jhomolhari, a region blissfully untouched through the centuries. We traveled over rocky trails through deep forests of rhododendrons, bamboo, and ferns; we visited remote villages and dzongs and braved snow squalls and brutal winds as we traversed passes of nearly 5000 meters. We were lucky to spy blue sheep, barking deer, sambar, and Bhutan’s unique national animal, the tarkin, the size of a moose that looks like a cross between a gnu, a musk ox, and a goat.

ABOVE: The Tiger’s Nest Monastery.

On route, we visited Takstang or Tiger’s Nest Monastery, the iconic, cliff-hanging, gravity-defying structure where Guru Padmasambhava, who introduced Buddhism into Bhutan, meditated for three years, three months, three days and three hours as he battled the demons inhabiting Paro Valley.

ABOVE: Excited children watch the annual Buddhist festival.

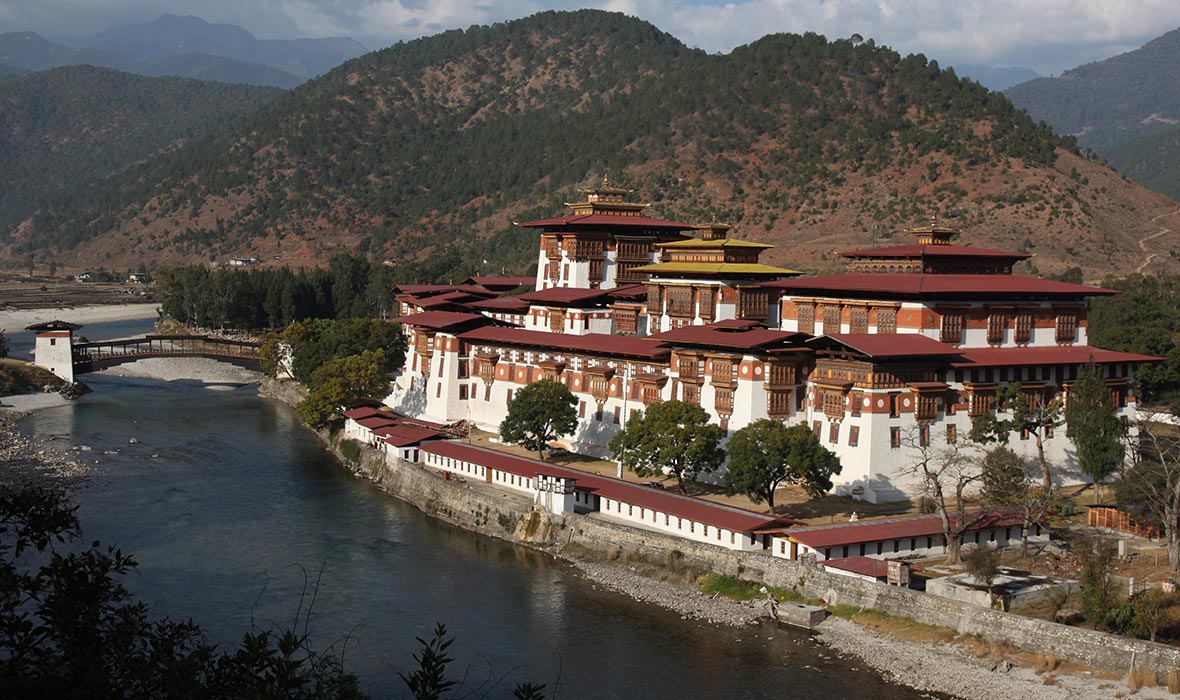

After a two-day drive from Thimphu, Earl and I attended the annual Buddhist Tshechus, held in Wangdue Phodrang Dzong, and Trongsa Dzong, colorful dance-dramas over a 4-day festival that take place yearly in Bhutan’s various dzongs.

The courtyards, crowded with local people dressed in their most colorful brocade clothing, watched in fascination as the rambunctious cham dancers, wearing dazzling silks and papier mache masks of demons and animals, banished evil and cleansed the visitors of sin while silly clowns alleviated the tension. A thongdrol (a giant thangka painted scroll) was unfurled and hung from the monastery walls.

ABOVE: A cham dancer performing in full regalia.

Three hundred or so rare black-necked swans, known as the “birds of heaven,” come to Phobjikha Valley in winter. Earl and I watched their fall arrival, when the flock flew three-times clockwise over the highly revered Gangtey Monastery, a Buddhist practice known as kora (circumambulation) to rid the body of negative energy. The birds repeat this feat during their Spring return to Tibet.

ABOVE: During the festival, performers banish evil and cleanse visitors of sin.

Unlike much of the Himalayan region, my own birthplace of Sikkim included, Bhutan has restricted the number of Western tourists who can visit and influence its fragile culture, which has allowed the country to ward off most of the challenges and excesses of modern life.

ABOVE: Punakha Dzong, the second oldest and largest dzong in Bhutan.

Bhutan’s unique ancient culture, traditions, arts and crafts, Buddhist religious heritage, and majestic architecture remains intact. Earl and I have visited Bhutan a number of times – Earl one of the first foreigners allowed to visit – and we always discover something new.