Beneath a stilted wooden home on the outskirts of Vientiane, a middle-aged Lao woman works a large loom. She smiles and greets me as her hands slide a narrow piece of wood from side to side, in and out of a sheet of silk threads, while rhythmically moving a larger wooden apparatus toward and then away from her, over and over.

Silk has long been one of Laos’ proudest products. Lao silk is especially fine, supposedly due to the worms’ diet of mulberry leaves. Silk makers then dye the threads using natural colors like pink made from sappan wood, red made from beetle shells, and blue from the indigo plant.

Lao people have been weaving these colorful threads for more than 1,000 years, creating not just attractive clothing but also bedding materials, artworks and household decorations. At the Lao Textile Museum, where I saw this skillful woman plying this ancient trade, master loom operators showcase their unique abilities to tourists while creating products that are sold by a community of artisans.

Their work is both difficult and endangered. It takes newcomers many months of being taught before they develop a strong command of the loom. Nowadays there are fewer and fewer experienced artisans available to teach the next generation. Many have retired or passed away.

There are also fewer and fewer young people interested in becoming fabric weavers due to its limited appeal in comparison to more modern occupations. Particularly in cities like Vientiane and Luang Prabang, Lao youths are now far more likely to pursue office work or retail jobs, or earn a university degree with the aim of working in a professional field.

Meanwhile, factories across Laos are pumping out cheap fabrics and silk products en masse, making it hard for traditional artisans to compete. While these factories can create an item of silk clothing in mere minutes, handmade versions can take many hours or even days to make depending upon their size and the complexity of their design.

This is why efforts are being made to preserve the ancient skills possessed by these weavers. That work is being carried out by places like the Lao Textile Museum, and the many silk villages across Laos which are open to the public, allowing visitors to gain an insight into the craft.

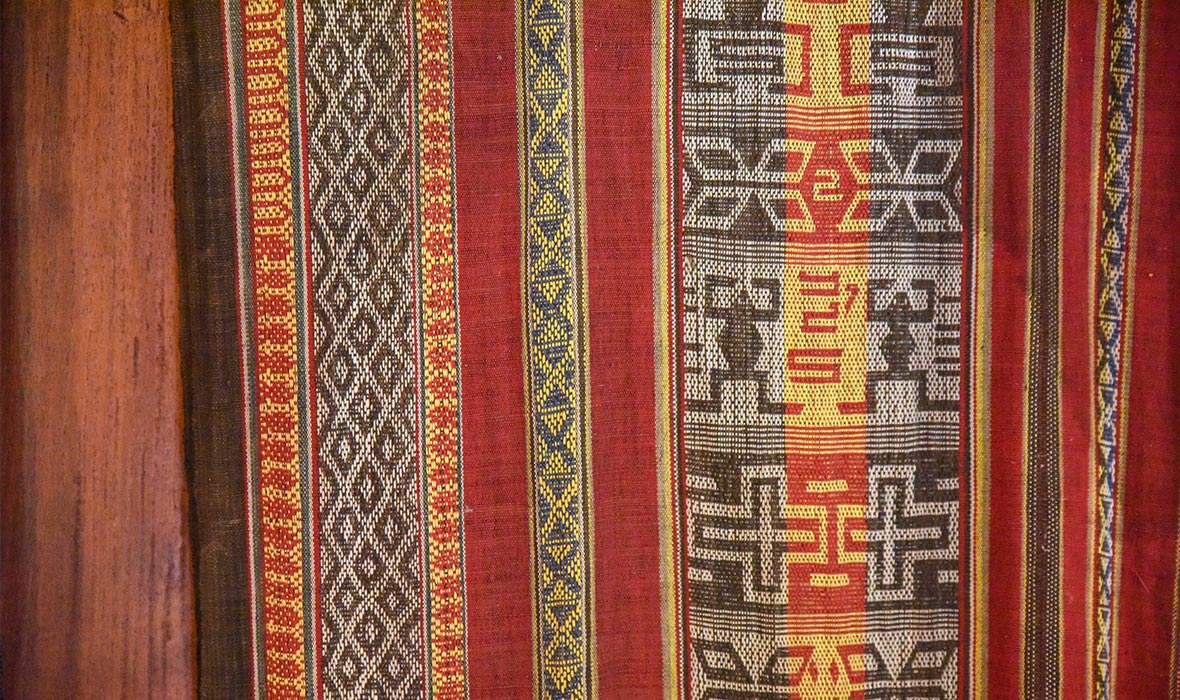

The artisan I observed at the Lao Textile Museum was making a traditional pair of Lao men’s pants, called Pha Hang. These silk cloths – typically around 4m in length – were wrapped around the waist, then passed between the man’s thighs and coiled around each leg before being fastened. Embellished with floral or geometric patterns Pha Hang were traditionally worn both in casual and formal settings, with more decorative versions donned on special occasions.

You can still see some older Lao men wearing these pants, particularly in smaller villages. But the popularity of Western-style clothes like jeans, shorts and t-shirts among young Lao people means that these unique forms of Lao garb of slowly dying out.

The most prominent piece of Lao clothing still commonly worn is the Phra Sarong for men and the Sinh for women. These lengths of fabric, which are similar in appearance, are wrapped around the waist creating a skirt and are more popular with females. Many of these skirts are made from silk, and the ones handcrafted by artisans are still widely seen as the superior versions.

These sarongs boast a huge variety of colours and designs, many of which are centuries old or inspired by ancient patterns. Native flowers and worshipped animals like the elephant are the most common motifs. Sarong designers choose to feature flowers which are viewed as being particularly auspicious in Lao culture.

Regularly featured on sarongs, the lotus flower is revered in Laos and even inspired the architecture of Vientiane’s That Luang stupa, which is the national symbol. The leaves of banyan and palm trees are also popular patterns for Lao silk fabric, with artisans often incorporating several different flowers and animals into one complex design.

The spiritual component to fabric designs is often provided by the presence of a Naga. Like a cross between a snake and a dragon, these mythical creatures are believed to live in the Mekong River, which acts as the border between Laos and Thailand for more than 800km. Donning an item of clothing embellished by a Naga is considered to bring its wearer good luck. That’s why they have adorned Lao fabrics for as long as the country’s artisans have been operating looms. Now these artisans need the help of the Naga to ensure their craft lives on.