Most Thais think of the town of Ubon Ratchathani in northeast Thailand as a base for touring outside the city rather than in the city itself. They head straight for prehistoric cliff paintings overlooking the Mekong River at Pha Taem, enchanting rock formations at Sam Phan Bok, the Moon River rapids at Kaeng Saphu, and dry-season beaches and ‘dancing shrimp’ at Sirindhorn Reservoir.

If they spend any time in the town itself, it’s usually for a pilgrimage stop at Wat Thung Si Muang, a Buddhist temple that boasts a historic ordination hall painted with 150-year-old Jataka murals, along with a wooden scripture hall standing on rickety stilts over a lotus pond. There’s also a huge annual candle festival, held in July to celebrate both Asanha Puja (commemorating the Buddha’s first sermon) and the beginning of the traditional three-month Buddhist Rains Retreat. Although originally intended as a way to supply local monks with candles to illuminate their living quarters in pre-electricity days, the focus today is a three-day parade of gigantic, elaborately carved beeswax sculptures around the town center.

While rock formations, temples, and festivals project a rather staid image of Ubon to outsiders, on a recent trip I discovered changes to the cultural landscape that are creating a new face for the city. Behind the changes is a young generation of Ubon residents who have returned to the city after working in Bangkok or abroad, some because of the economic pressures brought on by the pandemic, others simply because they realized they may have left behind a better lifestyle in Ubon.

These returnees bring perspectives from the outside world while still holding on to their Isan roots. One prime example, Eve Nutthida Palasak, operates Found Isan, a non-profit project that promotes local crafts re-interpreted for modern markets. With a master’s degree in fashion promotion from the UK’s Birmingham City University and a full-time position as a lecturer at Srinakharinwirot University in Bangkok, Eve thought she had left Ubon behind for good until her mother asked her to move back.

Upon her initial return, Eve sold harvesters and tractors in Ubon to the city’s sizeable agribusiness community.

I decided I wanted to do something more meaningful, something that used my skills to support locals at a grassroots level.

Eve Nutthida Palasak

“I made a lot of money, which I mostly spent on traveling and partying in Bangkok or overseas,” Eve told me. “But it left me feeling unfulfilled. I decided I wanted to do something more meaningful, something that used my skills to support locals at a grassroots level.”

Eve left her job to work with One Tambon One Product (OTOP), the government-sponsored local entrepreneurship stimulus program, to encourage village communities to improve the quality and marketing of local products. The project required that she drive from village to village in lower Isan for two months to survey OTOP potential.

“It was my first time to explore Isan [northeastern Thailand],” she says. “Even though I’m from here. I started to see how amazing the region was, especially in textiles and weaving. Before, when I wanted to see new textiles, I would fly to Paris or Tokyo.”

“Once I discovered the talent here,” she says, “I decided to use my background in promotion to support the weavers’ skills in textile production.”

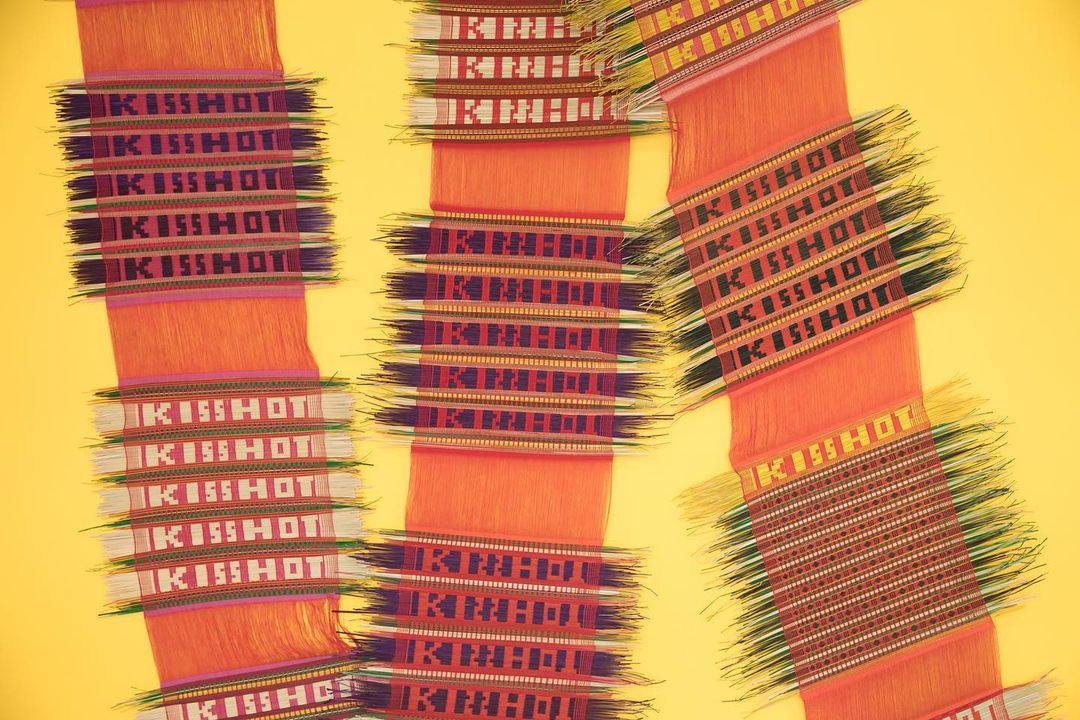

In Amnat Charoen, she came across a piece of fabric that she says changed her life.

“A village woman showed me a 40-year-old weaving into which she had woven the phrase ‘I’m Always Waiting for You’,” Eve says. The weaver explained that when she was 18 years old, her boyfriend decided to move to another city for work. She wove the fabric as a going-away gift for him, but in the end, he never came back.

“When I saw the fabric, I was so inspired that I decided to help her textiles reach many people around the world.”

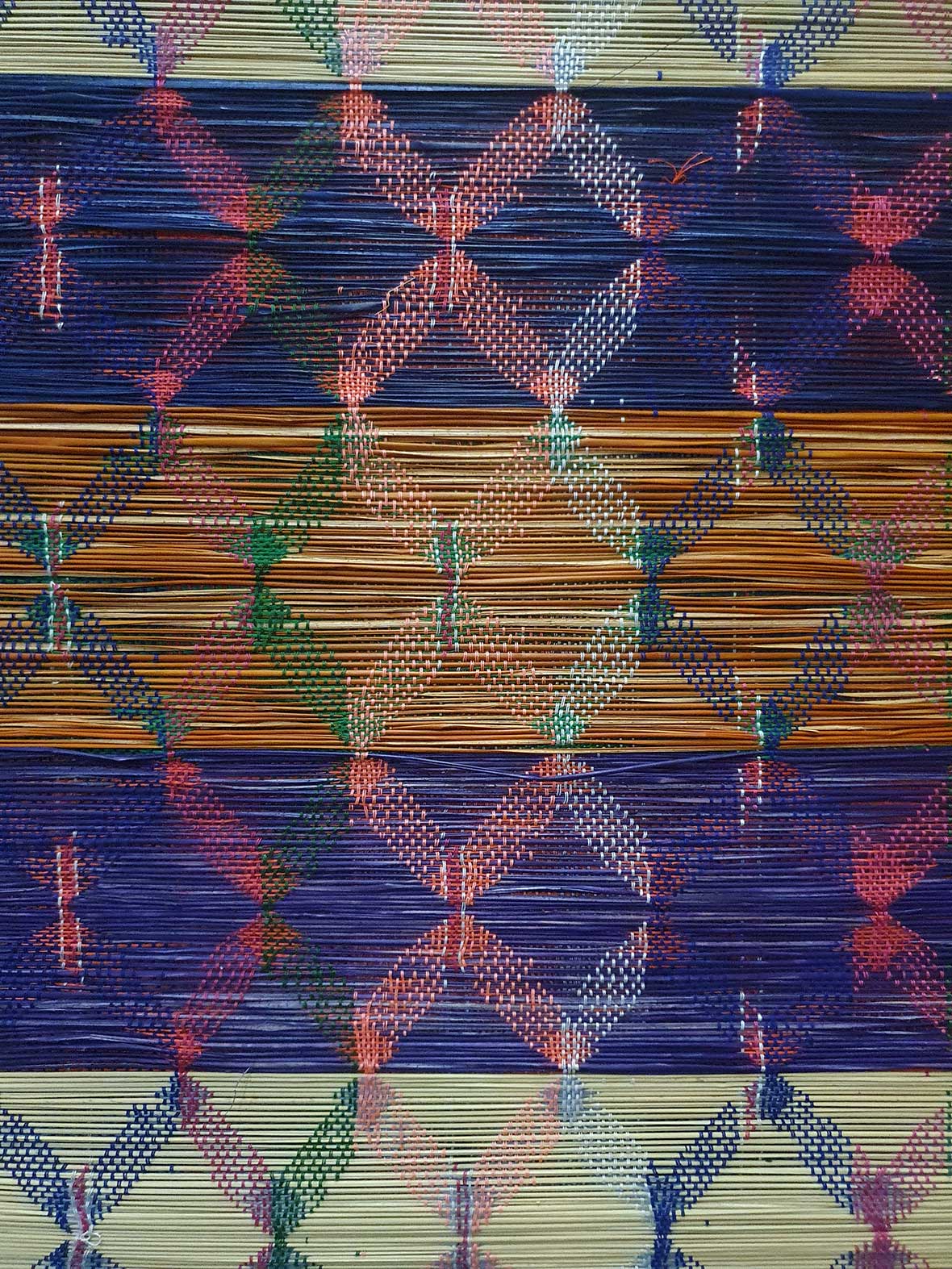

Today Eve’s foundation markets a variety of fabrics, mats, and wall hangings that include the slogan as well as related romance-oriented slogans such as “Don’t Lie to Me” and “I Love You Strongly” in the local Lao dialect.

Eve has since branched off into local cuisine, founding Zao Ubon, a restaurant focused on authentic, uncompromised Ubon cooking. Many of the recipes come from Aunt Jui, the nanny who raised her. You won’t find central Thai-style naam plaa (pasteurized fish sauce made with saltwater fish) at Zao, only real local plaa raa (non-pasteurized fish sauce made from river fish and sticky rice). Even snooty Bangkokians who claim to find plaa raa disgusting are usually won over by the rich flavors at Zao.

Lately, Ubon returnees are moving into the old city center between Thung Si Muang, the town square, and the banks of the Moon River. Years ago, municipal markets, gold shops, tailors, and sundries shops flourished in this area, but as Ubon expanded and supermarkets and shopping plazas moved to the city periphery, the 50- to 100-year-old shophouses downtown began to empty and decay. The old center further suffered after the municipal government relocated Ubon’s main inter-provincial bus station from downtown to a highway location.

Abandonment and decay turned into an opportunity after a new generation of Ubon residents found the lower rents and aging patinas of the buildings perfect for the creation of cafes, restaurants, and art studios.

One of the most inspired and successful developments is Impression Sunrise on Phalochai Road, where an abandoned four-story building with an empty lot out front has been renovated to become a vivid cultural hub anchored by a café, two restaurants, a cocktail bar and a studio/gallery hosting exhibitions and art workshops.

Three friends, Pakornpot ‘Jo’ Khananurak, Kingkanut ‘Mint’ Rongthong, and Watcharaporn ‘Ouan’ Somboon, share managerial responsibilities. The Chinese-themed Gu Huo Zai, named after the 1990s Hong Kong movie of the same name (English title: Young and Dangerous), tends to fill up with the eager young every night and provides the main revenue sustaining Impression Sunrise. A spacious garden downstairs, meanwhile, sees a variety of events, including live molam (northeastern Thai folk dance music) performances, readings, and creative markets.

The most dynamic scene in town revolves around coffee shops occupying the town’s oldest buildings, many of which exhibit a distinctive Sino-French architecture typical of Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. One café owner I spoke to says the old town has seen at least one or two new café openings every month for the last two years.

The coffee scene has become a major draw for visitors to Ubon, not unlike in Chiang Mai, where coffee and coffee shops rule daytime social life. Many of the coffee shop startups here employ at least one barista trained in Chiang Mai.

Most old-town Ubon coffee shops share a similar aesthetic based on mismatched second-hand furniture, old photos, watercolor paintings, simple antiques, and exposed brick-and-plaster walls. Songsarn, in a narrow alley flanked by walls vividly painted with street art, is one of the most popular new cafés, with a daily crowd spilling out of the relatively capacious two-shophouse front to small tables in the alley. Apart from serving coffee and pastries, the owners offer the space for art exhibitions, music events, and talks.

One of my favorite cafés in old Ubon is Secondary, the only place in town where the baristas use manual espresso pumps. This brewing method allows greater control over just about every variable in the brewing process, from water temperature to pump pressure, when compared with automatic espresso machines. The rich, all-Arabica house coffee here blends beans from the Bolaven Plateau in Laos with beans from Chiang Rai and from Doi Mae Daet Noi in Chiang Mai.

A little outside the town center, Nap’s Coffee was one of Ubon’s house-roasted coffee pioneers. Their simple indoor-outdoor shed wouldn’t be out of place on a Berkeley, California, side street, with its walk-up window counters and patio tables. Recently the owners added a sandwich shop, Bun Away, next door so that one can enjoy coffee together with bespoke wraps and sandwiches with whimsical names like Wilbur and Ferdinand. Also of note is the more upscale Tree Cafe Rim Moon, where nearly every table affords a view of the wide, placid Moon River. Along with espresso drinks, the menu offers pastries, sandwiches, and one-plate Thai dishes such as phat ka-phrao. Unlike most of the other cafes in town, which tend to close in the late afternoon, this one stays open till midnight.

But long before the hipster cafes came along, Ubon had its own traditional coffee culture. Market vendors offer old-fashioned kaafae boraan, thick dark coffee made by pouring hot water through a long cloth filter filled with ground robusta beans from southern Thailand. The resulting brew is poured into small, tapered glasses, to which sweetened condensed milk is typically added before serving. This style of coffee can also be found in local coffee shops established by Hokkien immigrants decades ago. The owner of Ubon’s oldest Hokkien-style cafe, Ha Hong, brews perhaps the highest-quality kaafae boraan in town. A traditional morning repast here consists of a coddled egg served in a coffee glass with a small plate of pathongko, a southern Chinese-style crisp-fried pastry known as khanom khuu in the local Lao dialect.

One morning while having coffee at Songsarn, I bumped into local vlogger Pakorn Kaewwongsa, who has produced several high-quality videos covering the Ubon coffeeshop scene for his popular YouTube channel Prathet Ubon, promoted in English as Ubonland. Other video topics on his channel include profiles of Isan designers, the local meatball (luuk chin) culture, skateboarding in Thung Si Muang, and the impact of Covid-19 on the lives of local people.

“I want to tell ordinary stories that are so close to us that we often overlook them,” Pakorn told me. “We travel around admiring things outside Ubon, yet completely neglect what is special right here in our own city.”

An Ubonland episode about third- and fourth-generation Thais descended from Indians who immigrated to Ubon a century or more ago features the young Thai Sikh owner of the only Indian restaurant in town, Baan Khao Hom. The Bombay Biryani at Baan Khao Hom rivals any I’ve found in Bangkok, or even in Mumbai, and the masala chicken, tikka kebabs, and tandoor-baked nan flatbreads are also highly recommended. Thai Sikhs run a number of other businesses in the old town, including fabric shops and pharmacies. Gurdwara Sri Guru Singh Sabha, the gleaming Sikh Temple on Ubonkit Road in the old town, opens its doors to non-Sikhs every Friday, offering free vegetarian food to all.

Ubon is famed throughout Thailand for laap pet, a spicy minced-duck salad that originated in Laos. Locals argue about which local spots serve the best, but many give the nod to Laap Pet Khon Leu, which operates two large branches, one on the Moon River southwest of the town center, and another in the north end of town.

Vietnamese dishes are standard fare in town, particularly kuay jap yuan, (tripe noodle soup) and paak mo yuan (bánh cuốn in Vietnamese, consisting of lightly steamed rice-flour paper wrapped around sliced pork sausage, ground meat, and bean sprouts), which can be found at any fresh market in Ubon and at small shops in the downtown area. A popular Isan-Vietnamese breakfast is khai katha, fried eggs in a hot pan alongside sliced Vietnamese moo yaw and Chinese khun siang sausages, and served with a small baguette stuffed with ground or shredded pork. In Vietnam it’s known as bánh mì chảo. Just about every local I met agreed that the best eatery for Vietnamese pan eggs is Ubon Ocha, a decades-old shop that’s packed from the moment it opens at 6.15 am until it closes its doors at 3 pm every day.

An interest in updating and promoting local cuisine has also steadily transformed the city into a dining destination. The most influential is the aforementioned Zao Ubon, where authentic Ubon delicacies are re-created in painstaking detail using 100-percent local ingredients. One of the standouts here is a sort of somtam made with chunks of fresh watermelon instead of papaya, and unpasteurized plaa raa instead of regular Thai fish sauce. The city also boasts Mok, where Fai Sirorat Thawto, an experienced chef who has worked at several hotel restaurants in Bangkok, prepares a fine dining menu that mixes both central and northeastern plates.

New-gen entrepreneurship takes on a fresh twist at BrandKnew Shop, which sells custom-made skateboards and skateboard components, including decks, wheels, and hardware, along with skating apparel. The staff also trains customers interested in learning how to skateboard.

Philadelphia Bookstore in Warin Chamrap District, 15km from Ubon town center, carries both new and second-hand titles, from children’s picture books to incomprehensible philosophy texts in Thai and English. Owner Jeab Wittayakorn Sowat, himself a writer, says “People who dare to buy books these days must have a strong love for reading. It’s a bold purchase. It’s not like buying candy or beer — you have to spend time with a book.”

A new wave in Ubon hotels compliments ongoing trends in coffee and cuisine. Vela Warin, a boutique heritage hotel in Warin Chamrap District, started life as a three-story warehouse built by a Chinese merchant family in 1937 to store goods shipped along the Moon River to and from Ubon. At one point the family converted the building into Hotel Sakon, which operated for over 20 years before reverting to storage. Around five years ago, Apiwat Suparkon, from the family’s third generation, took over the building and made it into a hotel once again.

Together with architect Woraphan Klampaiboon of SuperGreen Studio in Bangkok, Apiwat spent a year retrofitting the building to achieve modern standards without sacrificing architectural character. When admiring the original floor-to-roof wooden beams, for example, I noticed they receive additional support from parallel steel I-beams. The hotel offers 11 rooms, which include two spacious ground-floor rooms facing a garden courtyard and nine upstairs rooms. All are decorated with Isan fabrics and handicrafts in subtle, updated ways rather than the more tourist-trap Isan-styled hotels seen elsewhere. An Isan-inspired breakfast, with artisanal-quality coffee, is included for all guests. All-day dining, as well as espresso drinks and cocktails, are available in the hotel’s Velabar bistro.

North of the Moon River in Ubon Town, De Lit Hotel presents a completely different image, with a modernist Moroccan-meets-Mediterranean look, replete with arabesque arches, hand-plastered walls, and rustic wooden furniture. The hotel boasts a swimming pool, which is especially welcome during Isan’s fierce hot season.

There are regular flights between Bangkok and Ubon, but I opted for the overnight train. Chugging out of the sprawling capital at night, and then waking to farms and villages outside the windows, before arriving at Ubon’s 1930-vintage railway station, turned out to be the perfect city-to-countryside transition.