A few months ago, Mexican film artist Luis Palomino invited me to sit down and watch the 1974 erotic blockbuster Emmanuelle on his laptop.

Luis was thinking of producing a documentary that draws parallels between the loss of innocence of the French film’s main character and that of the city of Bangkok itself in the plus 40 years that have passed.

We fast-forwarded through the sex scenes—which are tame compared to what you can see in today’s mainstream cinema—so that I could comment on the Bangkok locations scattered throughout the picture.

Although I’d seen it once long ago, the fresh viewing left me with a new appreciation for the production that launched 70s soft-core with its gauzy dresses, wicker chairs and Vaseline-smeared lenses.

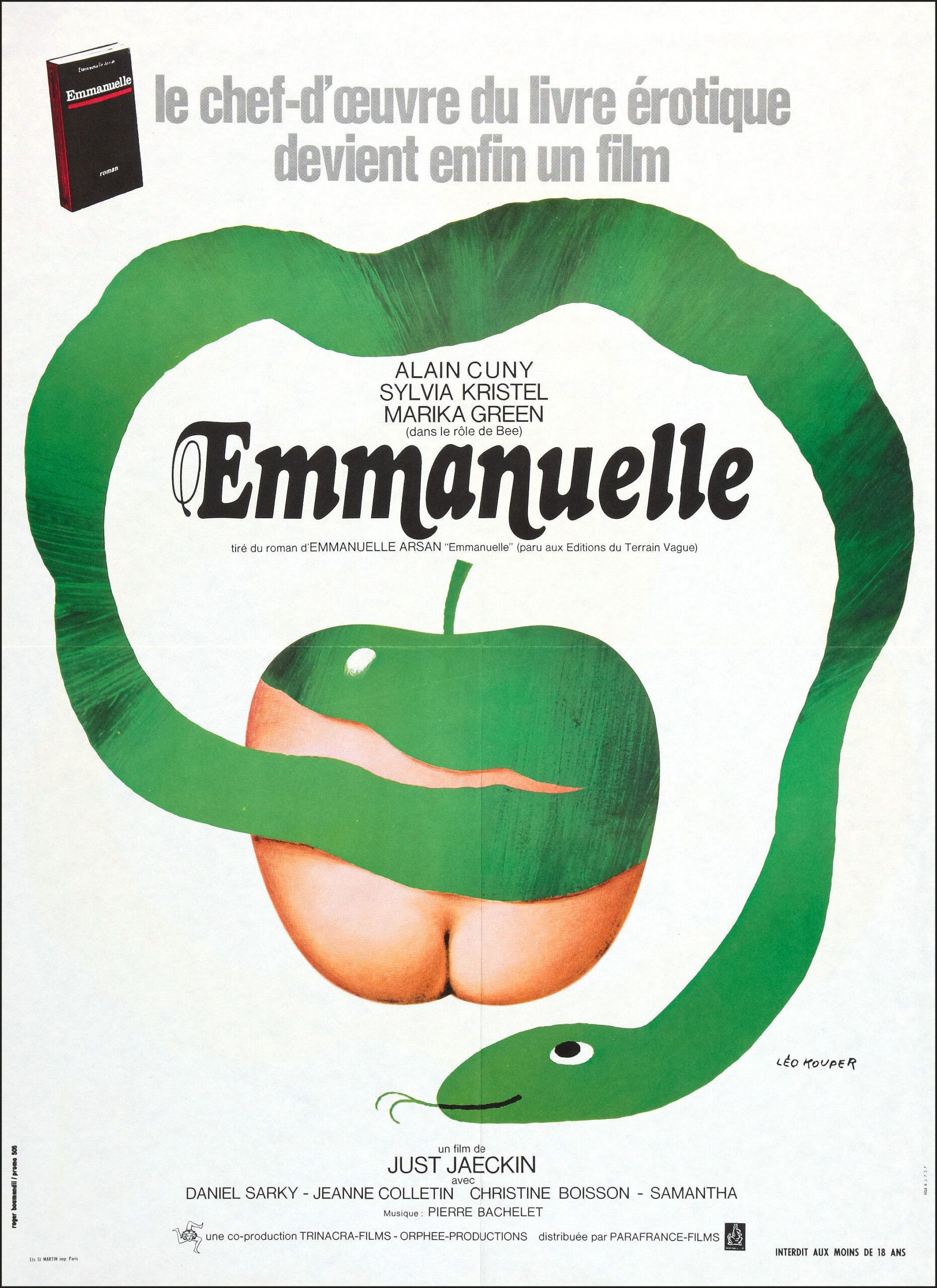

Based on a 1966 novel that was attributed to Thai author Emmanuelle Arsan, Emmanuelle enjoyed such success after opening in Paris that it ran for 13 consecutive years at Le Triomphe cinema on the Champs-Elysées. In the USA, where Columbia Pictures released the film, it became one of few X-rated movies to enjoy commercial success there.

Growing out of the late 60s/early 70s sexual revolution, the film signalled an era during which birth control was universally available, AIDS was non-existent, and pleasure without responsibility seemed like a dream come true. All you had to do was board a plane to Bangkok.

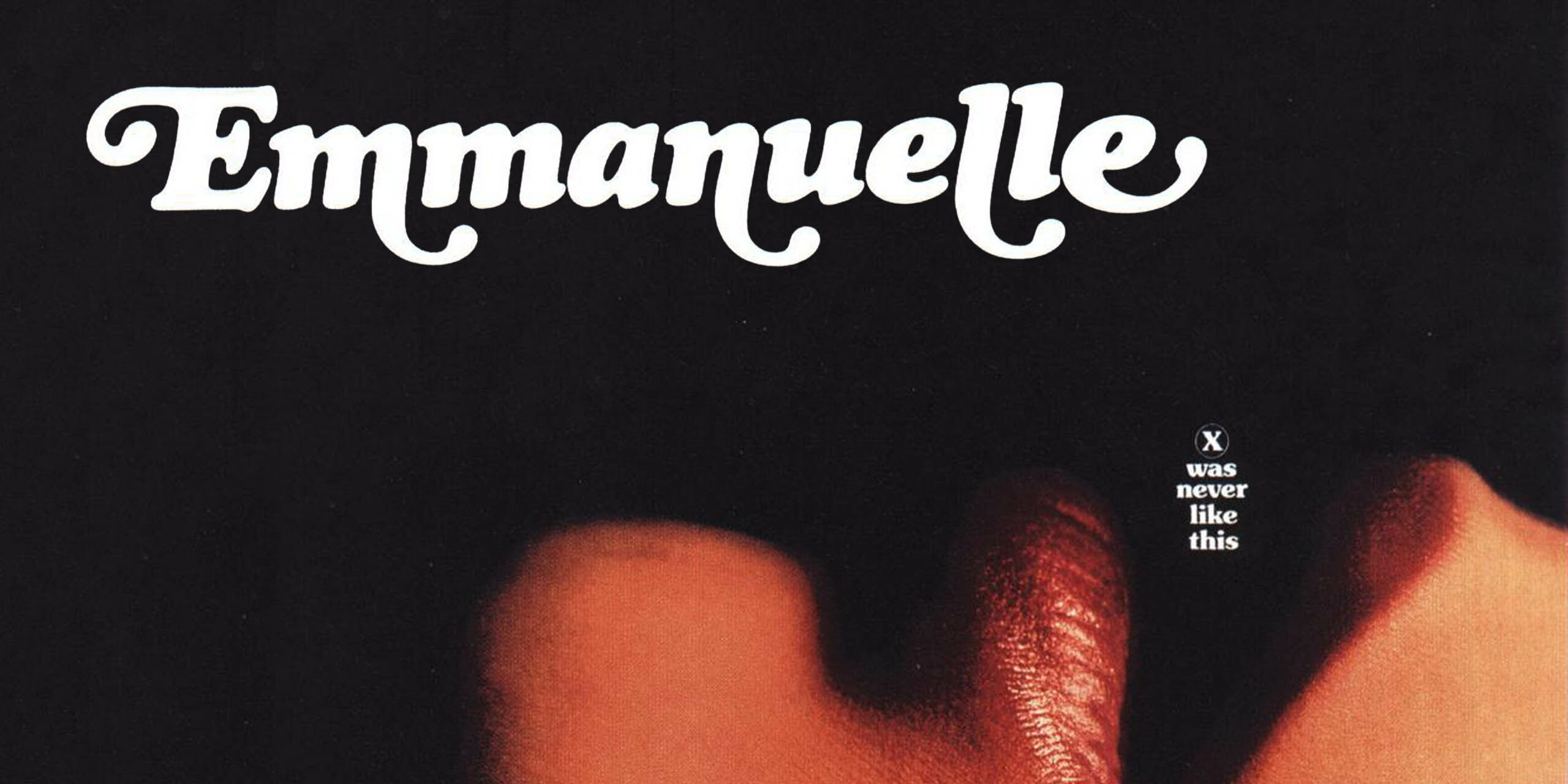

The 1974 film follows young and beautiful Emmanuelle (the producers originally wanted an Asian actress, but in the end chose Netherlands native Sylvia Kristel for her “ingenuity, and purity”) as she joins her diplomat husband Jean in Bangkok. Her erotic voyage of self-discovery, amongst a jaded, hedonistic group of European expats and locals, takes place entirely in the capital and environs.

Through the lens of first-time director Just Jaeckin, who had studied interior design and architecture in Paris, where he produced fashion layouts for Vogue, Elle, and Harper’s Bazaar, Bangkok is transformed into a lush, bold character of its own.

Locations are almost entirely drawn from Bangkok and Chiang Mai, although a few scenes were later shot in the Seychelles.

The cameraman is Robert Fraise, who was subsequently nominated for an Oscar for his cinematography in Jean-Jacques Annaud’s The Lover. Jean-Louis Richard, who adapted the novel for screen, had also co-written screenplays for François Truffaut’s The Soft Skin, Day for Night, and Fahrenheit 451.

The first Bangkok scene arrives five minutes into the film, as a yellow Jaguar convertible weaves past a Thai cinema house in Wang Burapha. Jean is at the wheel, and he says to Emmanuelle, “It’s always the same faces. Ex-adventurers, diplomats. They’re dying to see you.”

The Jag continues through Chinatown and over a bridge spanning Khlong Phadung Krung Kasem. The canal is seen at several other points in the film, along with other canals extending deep into Thonburi, and the Wat Sai floating market (now an infamous tourist trap). The partially ruined temple of Thonburi’s Wat Daowadeung also makes an appearance, along with a bit of the Makkasan neighborhood.

The frequent lovemaking takes place behind mosquito nets, and amid a Muay Thai brawl as well as other stereotypical ‘Thai’ contexts that include local participation.

On my recent viewing, it struck me that sex was little more than a time-killer for the characters. We’re reminded of this when Jean says: “Here we have only one enemy, boredom.” Emmanuelle eventually absorbs the program, and comes up with “Here, idleness is an art form.”

While shooting in Bangkok, the actors and crew stayed at The Siam Intercontinental, which stood on 26 acres of Thai royal property in the heart of Bangkok. A few film scenes – none of them sexual in nature — were shot among the ponds and gardens of the vast hotel, which was demolished in 2002 to make way for Siam Paragon and Siam Kempinski.

“Here, idleness is an art form.”

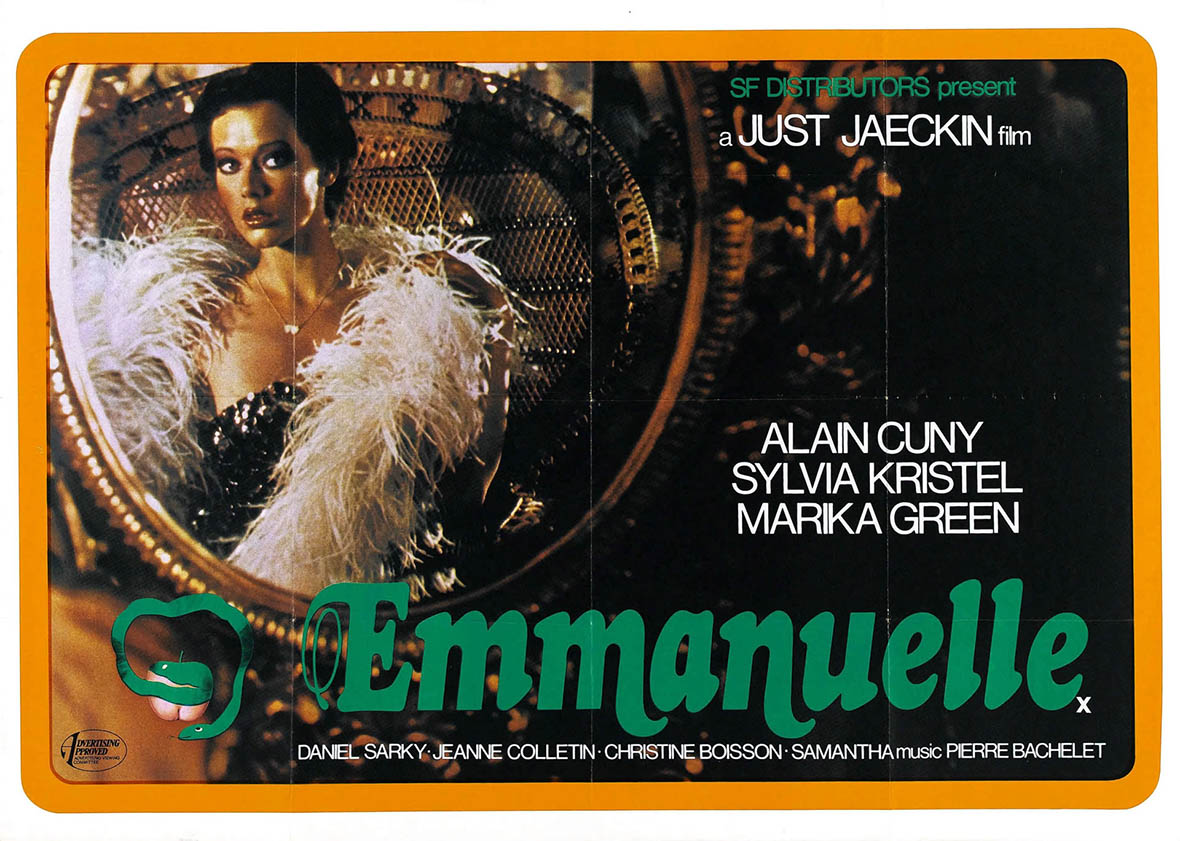

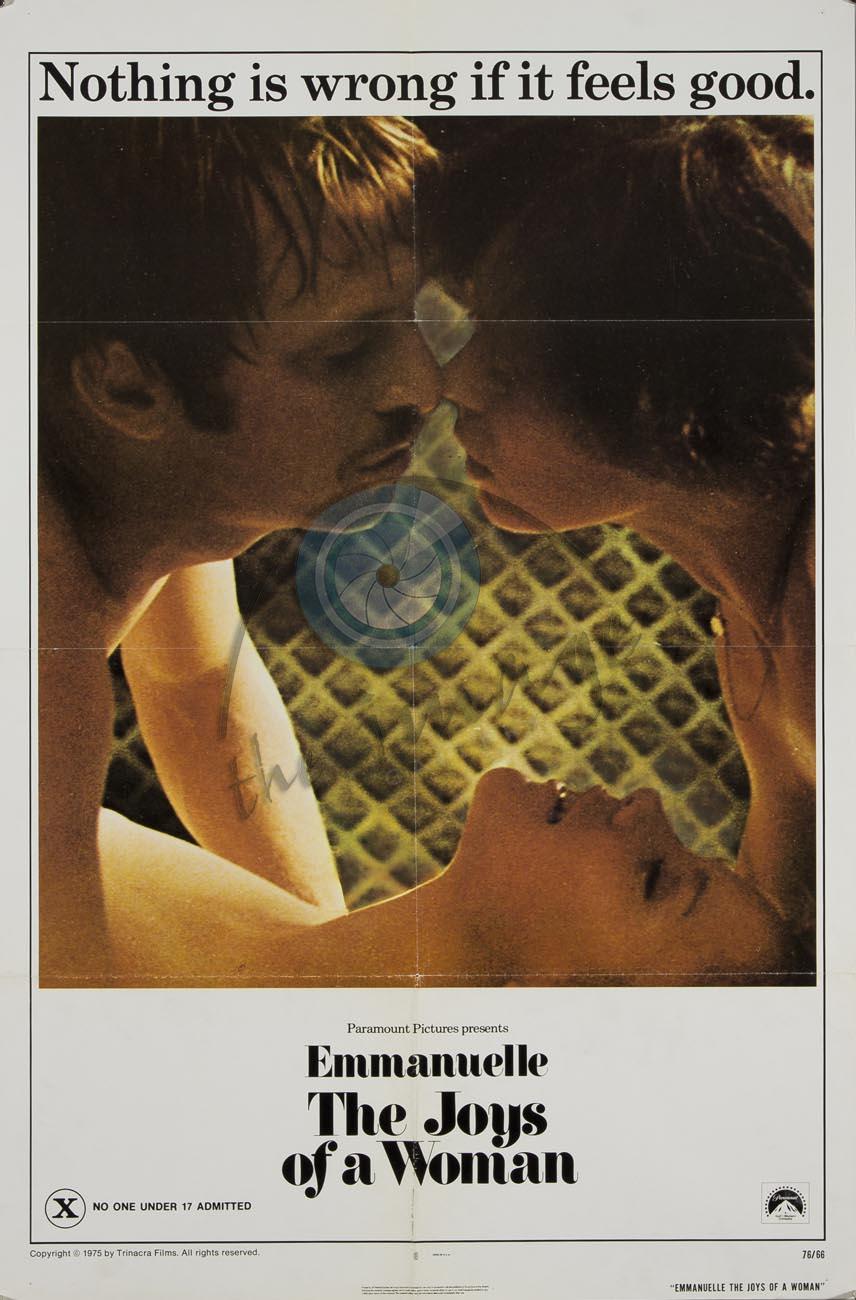

An estimated 500 million people have viewed the film around the world, spawning global brands for both Emmanuelle and Bangkok. Over a hundred sequels—more than any other film in history—have been released, starting with Emmanuelle 2 in 1975 and continuing most recently with Emmanuelle in Wonderland in 2012.

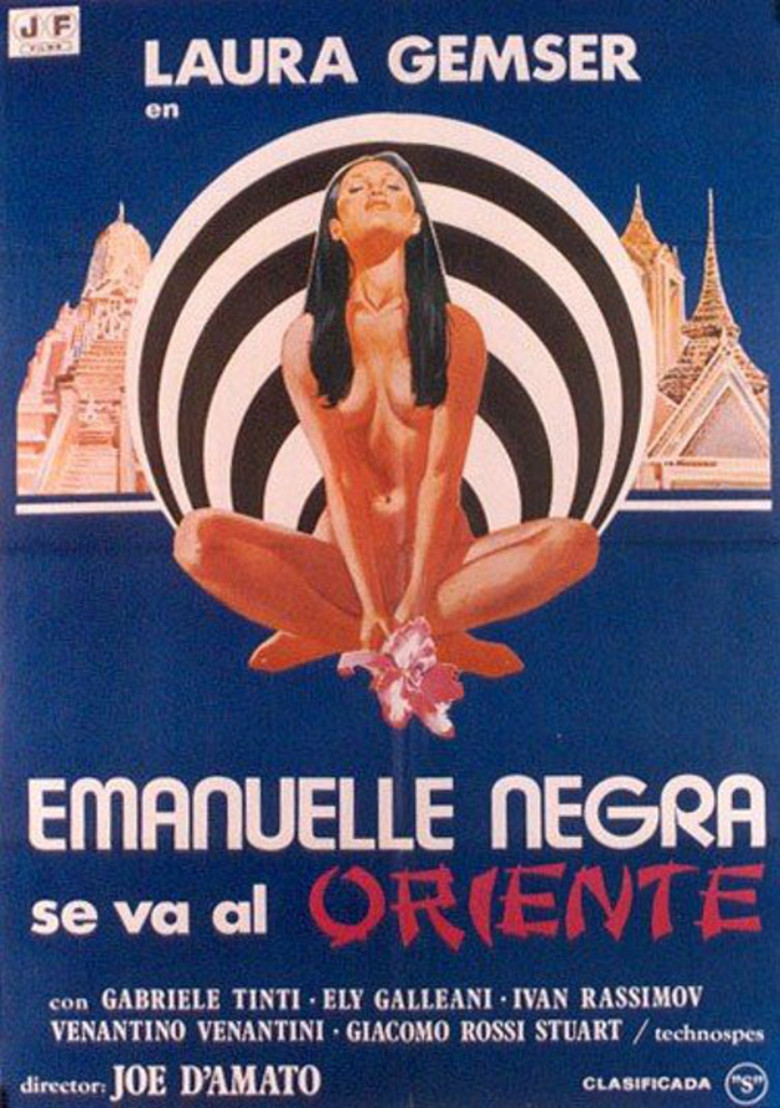

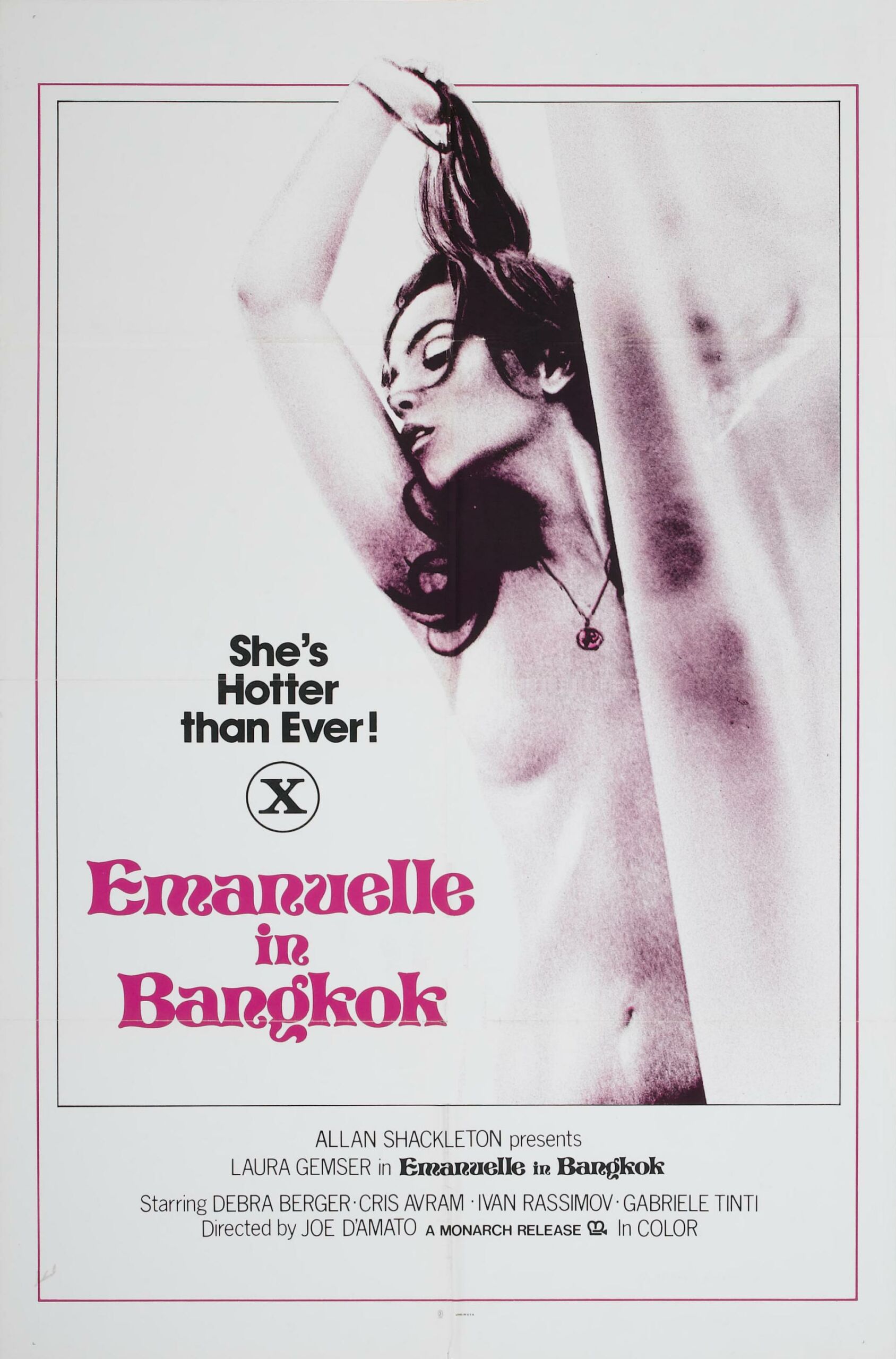

Many derivatives drop an ‘m’ in their titles (in an apparent attempt to avoid lawsuits from the original producers), as in the successful Black Emanuelle series starring Java-born Laura Gemser. Some of the more outlandish titles include Emanuelle and the Last Cannibals (1977), Kung Fu Emanuelle (1992), and an entire series of Emanuelle in Space episodes.

The original story’s jet-setting characters, philosophical amorality, and glamorous settings created a new softcore chic, while the world at large forgot that Emmanuelle was based on a novel.

Although officially published in 1966, the book was first distributed clandestinely and anonymously in France in 1957 as Joys of a Woman. Later editions bore the nom-de-plume Emmanuelle Arsan, who was later revealed to be Marayat Bhibhit (born Marayat Krasaesin), a woman of aristocratic Thai descent.

Born in Bangkok in 1932, the year of the Siamese Revolution, Marayat was sent by her parents to complete her studies at Switzerland’s prestigious Institut Le Rosey boarding school. There the 16-year-old Marayat met her future husband, French diplomat Louis-Jacques Rollet-Andriane, who was 30 at the time. After marrying in 1956, the couple settled in Bangkok. Years later it came out that the novel Joys of a Woman was a collaboration between Marayat and her husband.

Emmanuelle’s international crew would not have been permitted to shoot the erotic tale in Thailand without the assistance of Thai filmmaker Prince Bhanubandhu Yugala. A grandson of King Rama V, the influential prince provided a palace which serves as Emmanuelle and Jean’s rental home in the movie. After Thai police arrested Sylvia Kristel and crew for shooting a nude bathing scene at Khao Yai waterfall, the prince helped obtain their release and invited the producers to complete filming at his Assawin Pictures studios in Bangkok.

During post-production, editor, and Truffaut disciple Claudine Bouché dumped much of the pseudo-philosophical dialog originally intended for the ending. Instead, she shows Emmanuelle gazing into a mirror alone, suggesting the whole thing might have been a dream. The gauzy feel of vintage cinema adds credence to that notion. But Thailand’s involvement in one of the movie world’s most enduring love stories was very real.