Srinagar has long been considered a mystical and captivating place. The Kashmiri capital was initially considered a retreat from the summer heat and haze of the Indian plains. In the late 19th century, British officials of the East India Company got around the Kashmiri Maharajah’s ban on foreigners buying land by renting out hand-crafted houseboats on Dal Lake, setting the stage for what was later to become one of India’s most idyllic vacation escapes.

I stayed on a houseboat back in 1995, sitting on my veranda, staring at the mountains, and watching the world go by. If I needed anything, vendors in shikara rowboats would stop by my deck, paddling around the lake and hawking everything from fresh samosas to toilet paper. The houseboats were filled with vintage British Raj remnants, from poster beds to glitzy chandeliers and teak dressing cabinets, and it was easy for me to settle in and have a most rejuvenating stay.

Yet those were not happy times for Srinagar. Kashmir became a hot spot following the partition of India and Pakistan, and the 1990s saw the rise of a militant insurgency as well as a border war around Kargil. By 2000, with the area deemed unsafe, tourism was completely gone, and Srinagar’s houseboats were left empty.

Several decades later, domestic tourism finally began to revive, with Hindu pilgrims starting to make the journey to the holy Amarnath Cave, an ice cavern set high in the Himalayas, where a stalagmite formation said to be Shiva’s lingam is the focus of now some 300,000 worshippers each summer coming to camp and pray at its base.

Today, while the Indian military still retains an overwhelming presence in Kashmir, life in Srinagar has picked up and is generally normal. There are no more curfews, restaurants are busy, streets are packed with shoppers, and tourists from all over the world are coming back not only for dreamy houseboat stays but to explore some unique sights that make Srinagar one of India’s most captivating cities.

Recovering from a few weeks of hard trekking in Kashmir’s verdant valleys, my wife and I began our stay in Srinagar, of course, on Dal Lake. The houseboats were still as grand as ever, and there were plenty of shikaras not only willing to sell us snacks, but also wanting to take us on tours across the lake. We opted instead for something a bit off the tourist radar, waking up at 4.30 am to make our way across the lake in the dark. We slipped into one of its narrow waterways, where we glided through canopies of water hyacinth, eventually emerging into the neighborhood of Karapura, where farmers who own plots of floating vegetable gardens set amongst the lotus pads gathered at dawn to sell baskets of collard greens, tomatoes, and bitter gourd.

The farmers, who are all men, bring their produce to the floating market on wooden dugouts before it gets hot, earning income to feed their families. It wasn’t a well-known tourist attraction, and the locals went about their business without bother, using the occasion as a social time as well, sitting in their boats chatting amiably with one another, and sharing pipe-loads of fresh tobacco as they watched the morning come to life.

While most visitors to Srinagar center themselves around the comings and goings along Dal Lake, walking around the lovely promenades and gardens that hug its shore, one can get an even better glimpse of Srinagar’s heritage by wandering along the Jhelum River. The waterway, the main artery of the city, flows from the Pir Panjal range down through Srinagar, and eventually through Pakistan. We spent several hours wandering up the Jhelum, where the crumbling yet still picturesque stately mansions lining its banks provide a window into what the city must have looked like at its zenith.

Here, we came across the Khanqah-e-Moula, a mosque also known as Shah-e-Hamadan, that was built in the 1300s, made entirely of wood, and constructed without nails. The pyramidal mosque has double-arcaded balconies and verandas, and its ornate interior features elaborate papier mache relief. We were warmly welcomed here, and after a brief look inside, followed small groups of pilgrims making their way around the building, which was full of dazzling architecture and detailed craftsmanship. The palette of colors used to brighten the facades and its intricate woodworking and artistry were amazing, and we lingered under the shade of large trees just off the river, admiring the artwork and enjoying the serene spot, a far cry from the touts and crowds along busy Dal Lake.

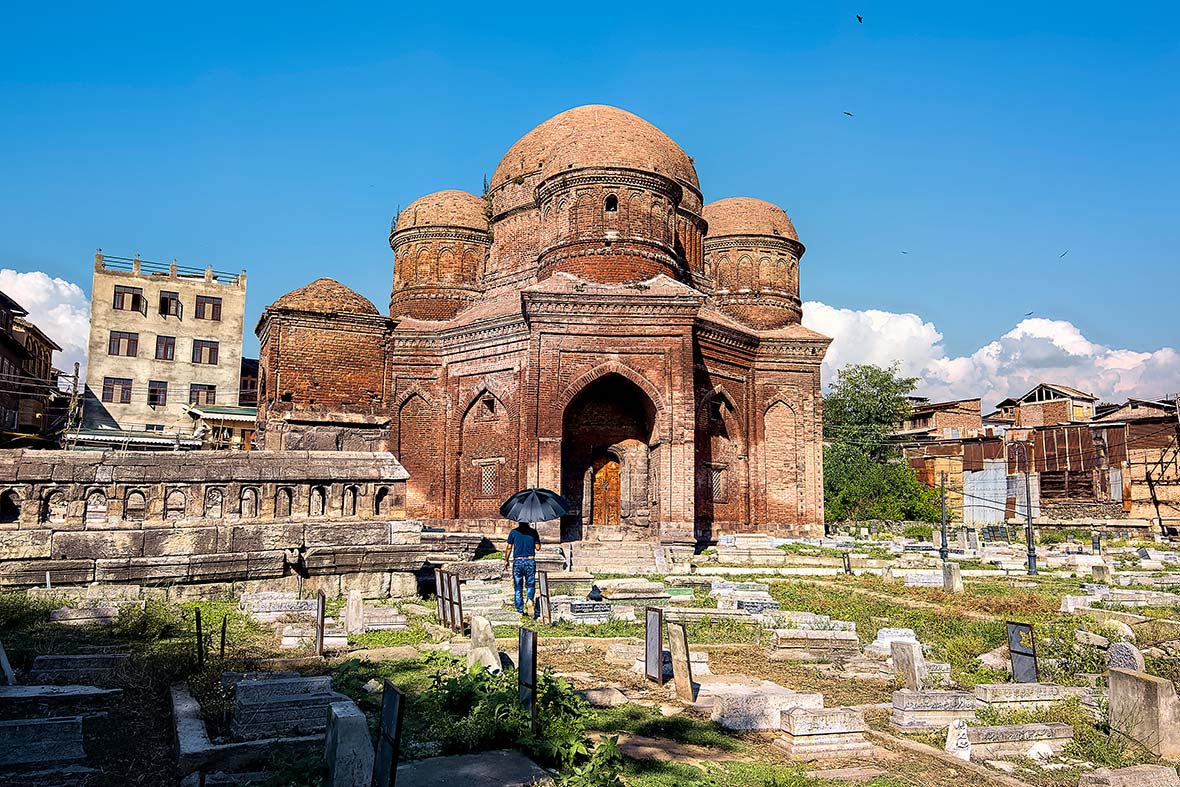

Not far from here, we stumbled upon the Tomb of Zain-ul-Abidin’s mother. Also known as the Badshah Tomb, this beehive-domed building looks more like a church from the Byzantine Empire than anything Islamic. It is the tomb of the mother of Sultan Zain-ul-Abidin, one of the most beloved rulers of Kashmir. Built in 1440, it was made from brick and engraved with glazed tiles and sits surrounded by local gravestones in a small cemetery.

We were the only visitors that afternoon, but a caretaker quickly appeared and invited us in for kahwa, a sweet Kashmiri tea flavored with cinnamon, cardamom, and saffron. He led us inside of the tomb, where the thick brick and tall domes kept the outside heat at bay. Mohammed, the caretaker, said he lived here year-round, and that the temperature inside was always cooler in the summer, and more importantly, warmer in the winter, when Srinagar turns frigid for months on end. Like most Kashmiris, we met in the city, he was hospitable, welcoming, and curious, yet not overbearing nor intrusive, something that we found vastly different from experiences we’d had elsewhere in India.

While Dal Lake might be the magnet of Srinagar, Lal Chowk is its hub and soul. Its name meaning “Red Square,” Lal was given its name by activists who were inspired by Lenin’s Russian Revolution. It was also the site of the first unfurling of the Indian flag after the Indo-Pakistan War of 1947-48, when India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, orated to the masses from here.

Boasting a large clock tower reminiscent of Big Ben, the plaza and surrounding streets leading across the river are home to bustling street markets, restaurants ranging from hip to hole in the wall, and vendors selling virtually every item under the sun. Old women sat on the Amira Kadal Bridge selling buckets of fish, hawkers with carts laden with giant juicy pomegranates and apricots and peaches in late summer cried out for custom, and bakeries with heaping piles of fresh nan, roti, and bagel-lookalikes called telvor catered to the crowds.

Wandering through this neighborhood, we found eateries serving large portions of rogan josh, Kashmir’s famed mutton curry, or the creamy yakhni, where meat gets marinated and cooked in a spicy yogurt sauce. These dishes are part of the elegant Kashmiri cuisine known as wazwan, made with region-specific spices and heavy on the meat and internal organs of sheep and goats. Wazwan cuisine is rich and heavy, so we’d only eat it every few days, opting most of the time for simple tandoori chicken, freshly baked in a clay oven, followed by a few rounds of sweet chai at our local corner stall.

I thought to myself about how perfect I’d seen my 1990s Dal Lake houseboat stay to be, having all the right essentials to make me want to linger longer. Yet with a tea in hand, our friendly chai-wallah smiling at us, and looking around at the Srinagar of today, I realized that it was perhaps now even more inviting for a longer stay.