For 1000 years across the Kathmandu Valley, water has been delivered by a fearsome creature. Part-elephant, part-snake, the makara is carved into stone at countless historic sites and has long fascinated tourists.

Now this Hindu deity is being asked to transfer its powers from the spiritual realm to the physical world to address chronic water supply problems plaguing Nepal.

The Makara decorate many of the old hiti fountains in the Kathmandu Valley. These ornate structures, which once provided huge volumes of water before most fell into disrepair, are being restored as key infrastructure, valuable cultural heritage, and unique tourist attractions.

Almost 20% of Kathmandu Valley residents don’t have water access in their homes, according to NGO, the World Monuments Fund. And even those who do are regularly affected by long interruptions to piped water supply. Into this breach could slither the makara and its hitis.

The WMF, which protects cultural heritage around the world, is spearheading the restoration of these unique fountains. It included them on its latest World Monuments Watch List. On its website, the organization explains that this list “spotlights 25 heritage sites of extraordinary significance, facing pressing challenges, and where World Monuments Fund’s partnership with local communities has the potential to make a meaningful difference.”

It has pledged to financially support Kathmandu authorities in revitalizing hitis. “Estimates from 2008 stated that they provided nearly three million liters of water per day,” the WMF says. “Today, only a fraction of extant hitis still provide water, and continuing development threatens their existence.”

Tourists can look into the intense eyes of a makara at many prominent hitis across the Kathmandu Valley. Among the finest specimens are in Kathmandu’s Durbar Square, the old town area of Patan, and the historic heart of Bhaktapur.

Meanwhile, a similar tale is unfolding in neighboring India. Authorities across that country have ordered the reconstruction of dozens of ancient stepwells as part of its own efforts to improve access to fresh water and restore cultural heritage.

Called baoli, these stepwells are not just effective but also magnificent. In Delhi and Hyderabad, I found myself transfixed by the ingenuity, craftsmanship, and photogenic properties of these subterranean structures. Baoli originated more than 1,500 years ago in India, where they once numbered in their thousands.

They had staircases which allowed people to easily access the water which pooled at their base. Many baoli were dug so deep into the ground that they were functional all year round. Worshippers could commonly be seen using the wells to wash their hands and feet in preparation for prayers at adjoining temples or mosques.

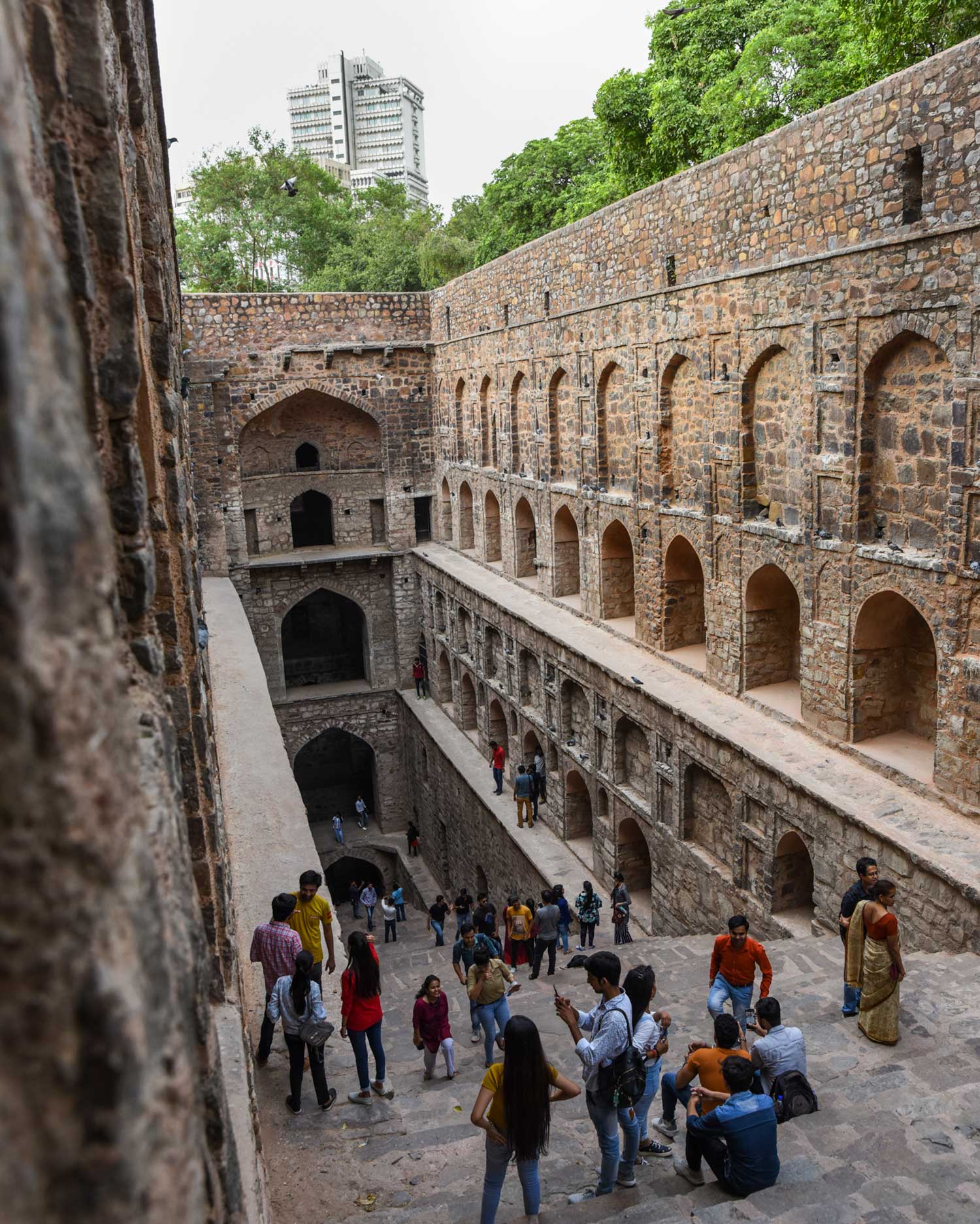

I imagined such rituals unfurling around me as I walked down 100 steps into Delhi’s colossal Agrasen ki Baoli. This 700-year-old stepwell is in the center of the Indian capital, near busy shopping precinct, Connaught Place. While that site is lined by Starbucks, McDonalds, Samsung, and Puma stores, a historic wonder of Indian architecture is a couple of hundred feet away.

This three-level baoli is lined by rows of stately arches, each one handcarved in red stone. I pondered just how many men, and how many hours, were required to meticulously shape this structure. Then I marveled at the artistry involved. Ancient Indian communities could have quickly dug working wells, but instead slowly and precisely created things of functional beauty.

So beautiful, in fact, that some have become social media stars. Such as Chand Bawri, in the arid state of Rajasthan. This stepwell displays such complexity, with 3,500 steps etched into its 13 floors, that it’s featured in endless Instagram and TikTok posts, and sits near the top of my India bucket list.

Partly due to their tourism value, Agrasen ki Baoli and Chand Bawri have been relatively well maintained. Far better than most of India’s stepwells, the decline of which can be traced to India’s British era. The occupying Brits viewed baolis as antiquated pits laden with germs, so they either razed or decommissioned most of them from the late 19th century onwards.

Many surviving baolis were left to degrade over the 20th century. Then, in recent years, the Indian Government began to look for ways to ease the country’s widespread water shortages. They recognized that reactivating ancient baolis could play a small role in addressing this problem, while also safeguarding a distinctive element of Indian culture.

Some States, like Telengana in central India, are so bullish about this project they’ve vowed to restore most of its more than 100 baolis. While that goal is distant, they’ve made fine headway. In March I admired the revived Badi Baoli.

The water from this majestic stepwell has aided the restoration of its sprawling necropolis in Hyderabad. It’s also helped attract tourists to this site, the Qutb Shahi Heritage Park. In both India and Nepal, then, neglected architectural treasures are being reborn to quench their populations, safeguard cultural heritage, and bewitch tourists.