The mountainous jungle stretches on and on, spanning the borders of Thailand, Myanmar, and Laos. From my lofty vantage at the hilltop Doi Tung Royal Villa in Chiang Rai Province, I can see across the northern Thai border into Myanmar. I know this only by judging the distance, not because there is any obvious visual marker indicating the line that separates the countries. This is wild, untamed land up here, with nature often more in control than man, a feature that once made this area the perfect venue for one of the biggest drug empires on the planet.

The view across this region is the same one once admired by the late Thai Princess Srinagarindra, the mother of the late Thai King Bhumibol. It was from up here, at her abode the Doi Tung Royal Villa, that Princess Srinagarindra spearheaded an ambitious project to tackle the drug lords of the Golden Triangle.

ABOVE: Doi Tung Royal Villa that hosted Princess Srinagarindra

This was not a military campaign, like the many drug wars tried and failed by governments across the world. Princess Srinagarindra sought to win hearts and minds rather than territory – coffee, fruit, vegetables, and flowers in the face of drug lords and their private armies.

Before delving into just how the Princess did achieved this, first it is necessary to understand how the Golden Triangle was formed. Opium has been cultivated by humans for more than 5,000 years, starting in the Middle East, and was first introduced to East Asia in about 330 BCE by Greek King Alexander the Great. The origins of the Golden Triangle can be traced back to the 1850s when the British, who had just defeated China in the first Opium War, began importing opium from India and created a massive drug operation in Burma. Within decades Burma had become a global hub for the cultivation and trade of opium, with vast fields in Shan State, the region of Myanmar which Princess Srinagarindra could see from her villa.

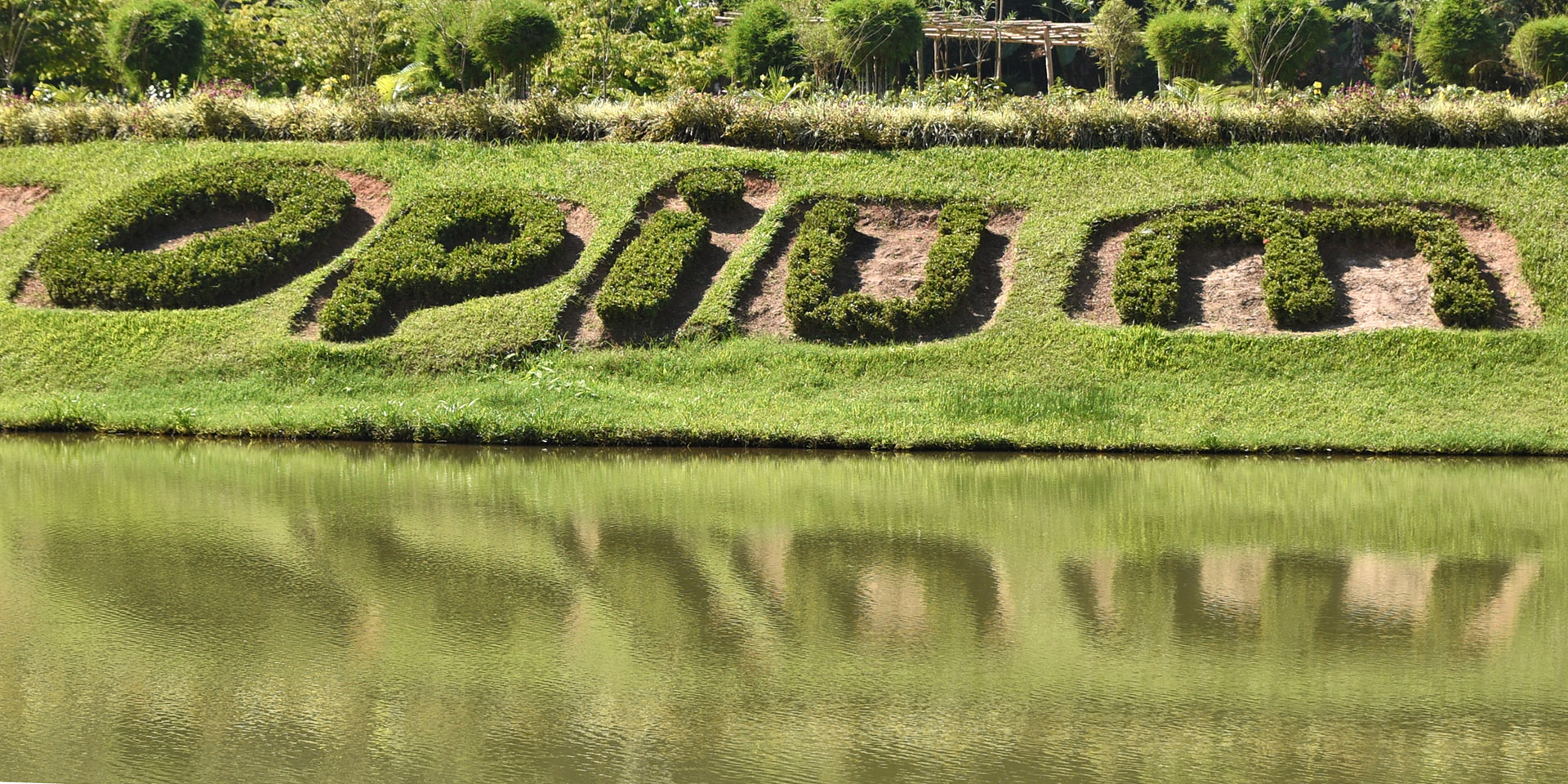

ABOVE: Mae Fah Luang Garden of the Golden Triangle.

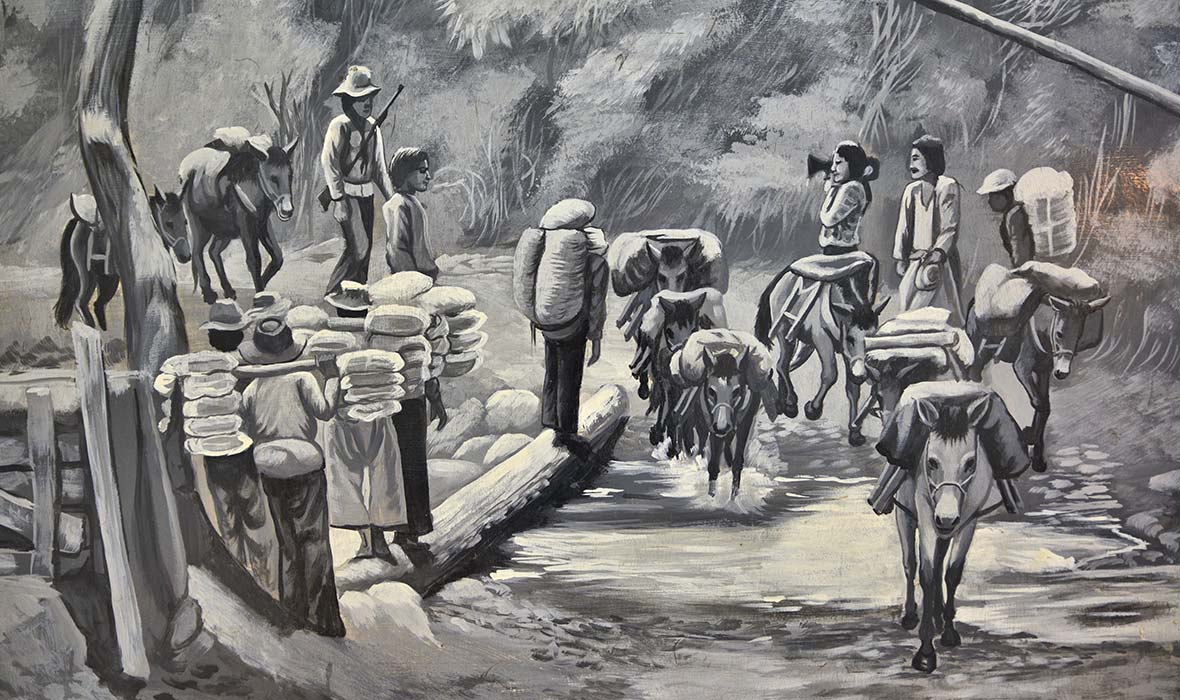

This opium cultivation spread into the northern reaches of Thailand, while a huge amount of Burmese-grown opium was also smuggled across the borders into Thailand and Laos. Involvement in this drug trade, even in a minor capacity, was much more lucrative and far less physically taxing than hard agricultural work, which was the other major form of employment in the Golden Triangle. Not surprisingly, many ordinary Thai people began to make their living by becoming a part of the drug supply chain.

By the time Princess Srinagarindra entered the Thai Royal family by marriage in 1919, the opium trade was dominant in northern Thailand. Later in life the Princess saw the drug problem from close quarters from her villa, which was built in 1988. Open for visits by tourists, this magnificent wooden mansion and the elaborate Mae Fah Luang Garden beneath it together form one of the most spectacular sites in Thailand. Constructed mostly from teak and pine wood, the Princess’ villa is like a Thai version of a Swiss chalet, with its gently sloping roofs, overhanging eaves and wide terraces.

ABOVE: Artist’s rendering of an opium caravan from the Golden Triangle drug trade.

It is from these terraces that tourists can enjoy the view across the mountains into Myanmar. It is hard, though, to take your gaze away from the extraordinary garden directly below the villa. Spread along the hillside, this 10 acre garden boasts intricate landscaping and hundreds of varieties of flora, and kept me beguiled for two hours as I wandered its many paths. Symbolically, this gorgeous garden was built on land which once was an important route for opium caravans.

The decorative flowers which cloak Mae Fah Luang Garden are cultivated by hundreds of local villagers who are trained to work there. This is part of Princess Srinagarindra’s successful campaign to offer locals good employment alternatives to being part of the drug trade. During her tours of remote villages in Northern Thailand in the 1960s, Princess Srinagarindra saw how reliant many villagers were upon the opium trade and so decided to take action.

ABOVE: Tourists mill about the Mae Fah Luang Garden.

The Princess’ campaign started in 1969 when she formed the Thai Hill Crafts Foundation, which encouraged and helped locals to pursue traditional crafts. This project complemented the Royal Project Foundation launched that same year by her son, King Bhumibol, which helped Northern Thai people become self-sufficient by cultivating fruit and vegetables instead of opium. The Princess’ Foundation soon expanded to foster the development of cash crops like tea, coffee and peaches. Both of these Royal foundations were a major success, with opium cultivation plummeting in northern Thailand as locals sought to instead produce legal crops.

Even at the age of 87, Princess Srinagarindra continued to fiercely pursue her campaign, creating the Doi Tung Development Project in 1988. Over the past 31 years this project has not only further encouraged legal agriculture, but has established drug rehabilitation services, centres for vocational training, and myriad other educational programs.

When Princess Srinagarindra passed away at the age of 94, she left behind a proud legacy. Granted, the drug trade has not been eradicated in northern Thailand, which remains a major smuggling route. But poor citizens of this region now have options. No longer are they reliant on becoming involved in this illicit industry to put food on their table. The Princess took on the drug lords and, in many ways, she won.