Sundeep looks surprised. He’s leaning against a handrail outside the Podar Haveli Museum in Nawalgarh, smoking a hand-rolled cigarette. As our taxi pulls up, he fixes his hair and lumbers down the stone steps.

It’s late in the afternoon, and the activity in this city of roughly 60,000 souls has lulled. The fading winter daylight has coated its sand-colored buildings with a further sepia-toned glow.

Despite the hour, my wife and I seem to be Sundeep’s first—and only—clients of the day. Yet something leads us to believe he would be just as content to spend the rest of the day smoking cigarettes on the museum steps instead of showing us Nawalgarh’s top—and, again, only—tourist attraction: the painted havelis.

“Okay, let’s begin,” he says casually and strolls into the museum as we clamber out of the car.

Nawalgarh, like our guide, flaunts a languorous personality. Arid and remote, it sits in an overlooked region known as Shekhawati in northeastern Rajasthan. Unlike the state’s core destinations, it lacks giant palaces or signature hues—Jaipur pink, Jodhpur blue, Udaipur white—to lure visitors.

Even with a bustling central market clogging traffic among the impossibly narrow lanes that fan out from it, the city lacks the chaotic convergence of daily life and tourism so common in the rest of Rajasthan.

What it does offer, however, is a glimpse into an incredibly unique period in Indian history.

When the Silk Road declined, Shekhawati merchants and traders moved to ports like Bombay and Calcutta to find work. As those trading hubs grew in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Shekhawati expats began to amass wealth. Yet whether for religious ceremonies, weddings, or family needs, they kept coming back to their homes in the desert. And they kept adding to them.

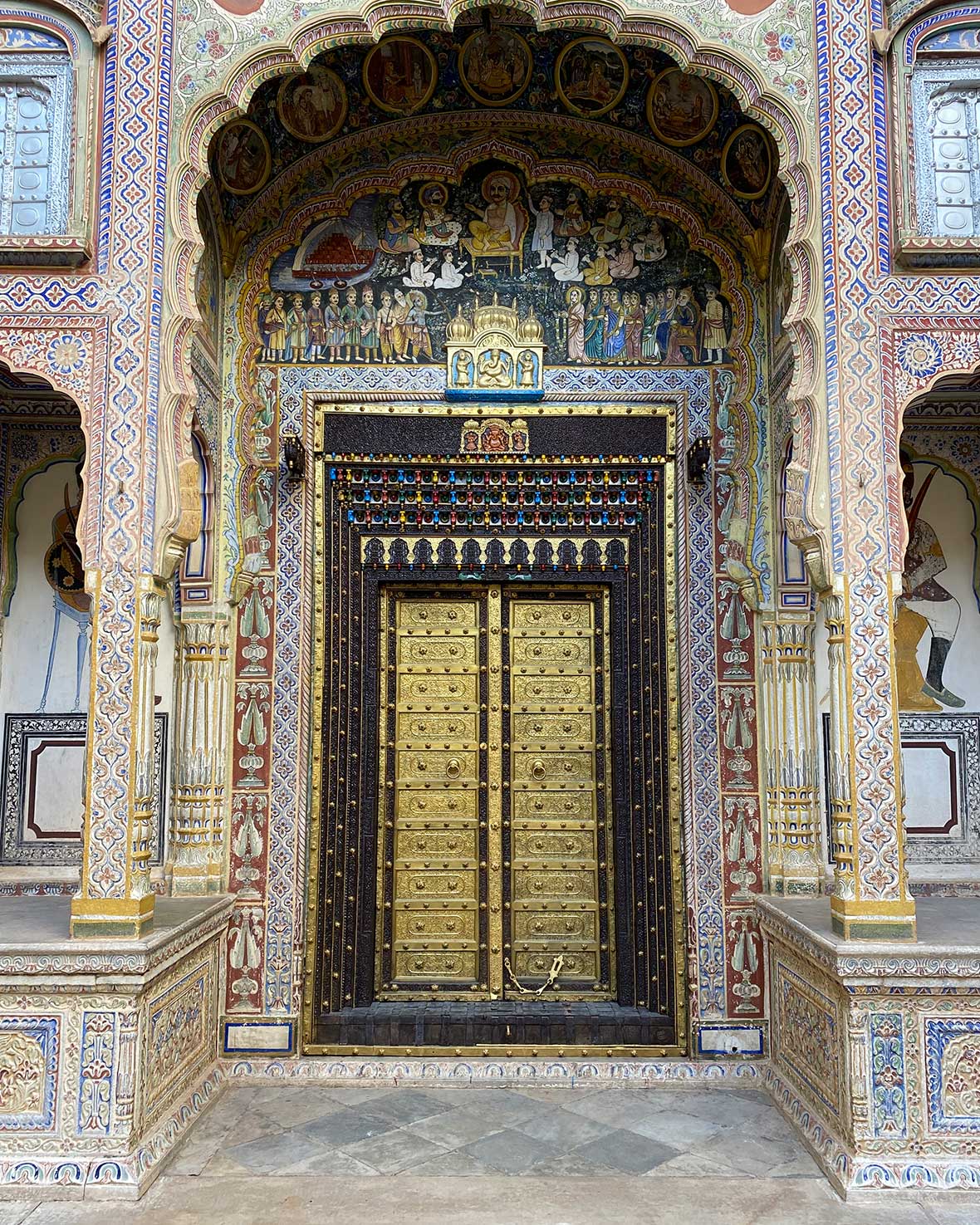

Like peacocks fanning their feathers, they flaunted their newfound riches. The merchants hired painters to cover their family mansions, or havelis, with extravagant and occasionally humorous murals and frescoes. These elaborate paintings depicted everything from Hindu deities to erotic scenes, maps of the world, engineering feats like trains and hot air balloons, and even British colonials.

From the door jambs to the windowsills, often no inch of wall space was left untouched. The exteriors even featured custom, painstakingly produced artwork, turning towns like Mandawa, Dunlod and Nawalgarh into open-air galleries as families competed to show how well-off they were.

“Nawalgarh is the best of them all,” Sundeep assures us as we make our way through the Podar Haveli Museum—the first stop of most, if not all, haveli tours.

Philanthropist Anandilal Podar constructed it in 1902, making it one of the younger havelis in the region. His grandson Kantikumar R. Podar later converted it into one of Nawalgarh’s only museums.

From meeting rooms featuring massive hand-pulled fans used by servants to keep their masters and guests cool in the fiery summer months to ornately decorated courtyards and bedrooms, the haveli offers a vivid look at the way Shekhawati merchants lived and did business in the past.

While rooms filled with dioramas of Rajasthan’s great palaces or dolls dressed up to illustrate India’s castes—“I’m a Brahmin,” says Sundeep, adding that “every Indian today” can identify other people’s castes by their surnames—seem ham-fisted, the space has otherwise been well-preserved.

As Sundeep leads us across the old part of town, we notice that almost every building has frescoes on the walls. The paintings are remarkably detailed: merchants riding elephants or rearing horses, chariots racing across the desert, Shiva, and his divine family. Most, however, are peeling into non-existence.

The buildings themselves have largely fallen into a state of disrepair, too.

“Havelis are privately owned. In most cases, the kids have gone to Delhi to work and don’t care about them, or family members disagree about what to do with them,” Sundeep explains. “So maybe someone in the family will pay for a person to watch over them, but they don’t pay to renovate them.”

In other words, the remnants of Shekhawati’s golden age are for the most part fading into the desert.

While some have been converted into hotels, most have been left to rot. As long as family in-fighting continues and state officials remain disinterested, their future looks uncertain, too.

For now, these unique buildings—and the unique characters who show them to you—still offer a worthwhile diversion within India’s Golden Triangle (Delhi, Agra, and Jaipur).

Pointing out the best angles for photos along the way, Sundeep leads us to Kamal Morarka, a haveli featuring 700 frescoes and 160 sculpted doors and windows. While we admire the renovated structure, he directs our attention to nearby cenotaphs. Here, he explains with a mischievous grin, some of the town’s teetotal Hindu men sneak away at night to smoke marijuana.

When we reach Bansidhar Bhagat Ji Haveli, Sundeep briefly disappears. We stand outside two large wooden doors until he returns with an older man wielding a set of keys. For 100 rupees (roughly $1), we’re allowed to enter one of the more fascinating buildings in the town.

The exterior walls feature oddly shaped depictions of trains and planes. “None of the painters had ever seen a plane or a train before, so they had to make them up from what other people said they looked like,” he explains as he bums a cigarette from the building’s caretaker and signals to us to look around.

The courtyard is in remarkable shape. Stone tile floors meet baby blue pillars and arched doorframes decorated with floral patterns in shades of maroon, indigo and forest green. Within seconds, Sundeep is looking down at us from a second-floor window, beckoning us to come upstairs. He removes his scarf and wraps it into a turban around my head. He asks for my wife’s phone, directs us to two adjacent window frames and snaps a photo I’m sure to regret if it ever sees the light of day.

When he comes back to us, he tells us how the small room we are in was used as a space for puppet shows and performances – entertainment in the days before TV and the Internet. “The children and women would sit in the loft space and watch the performers from above,” he says.

Finally, he leads us up narrow stairs to the rooftop. Dozens of havelis come into view below, revealing the scale of this small dusty town’s ancient wealth. Even Sundeep, who sees this same view every time travelers like us wander into town, seems impressed by Nawalgarh’s still living history.

“It was a great time for us,” he says, and then instructs us to squeeze closer together so he can take one more photo while I’m still wearing his makeshift turban.