The Mongol armies weren’t exactly considerate guests during frequent invasions of Korea: creating piles of corpses as a calling card. But they did leave behind one positive thing in particular, which continues to enliven society.

It can be cloudy or clear, robust or gentle, pungent, or mild, is drunk according to ancient protocols, and even helped South Korea tackle COVID-19. This is firewater (sool), South Korea’s mother alcoholic spirit.

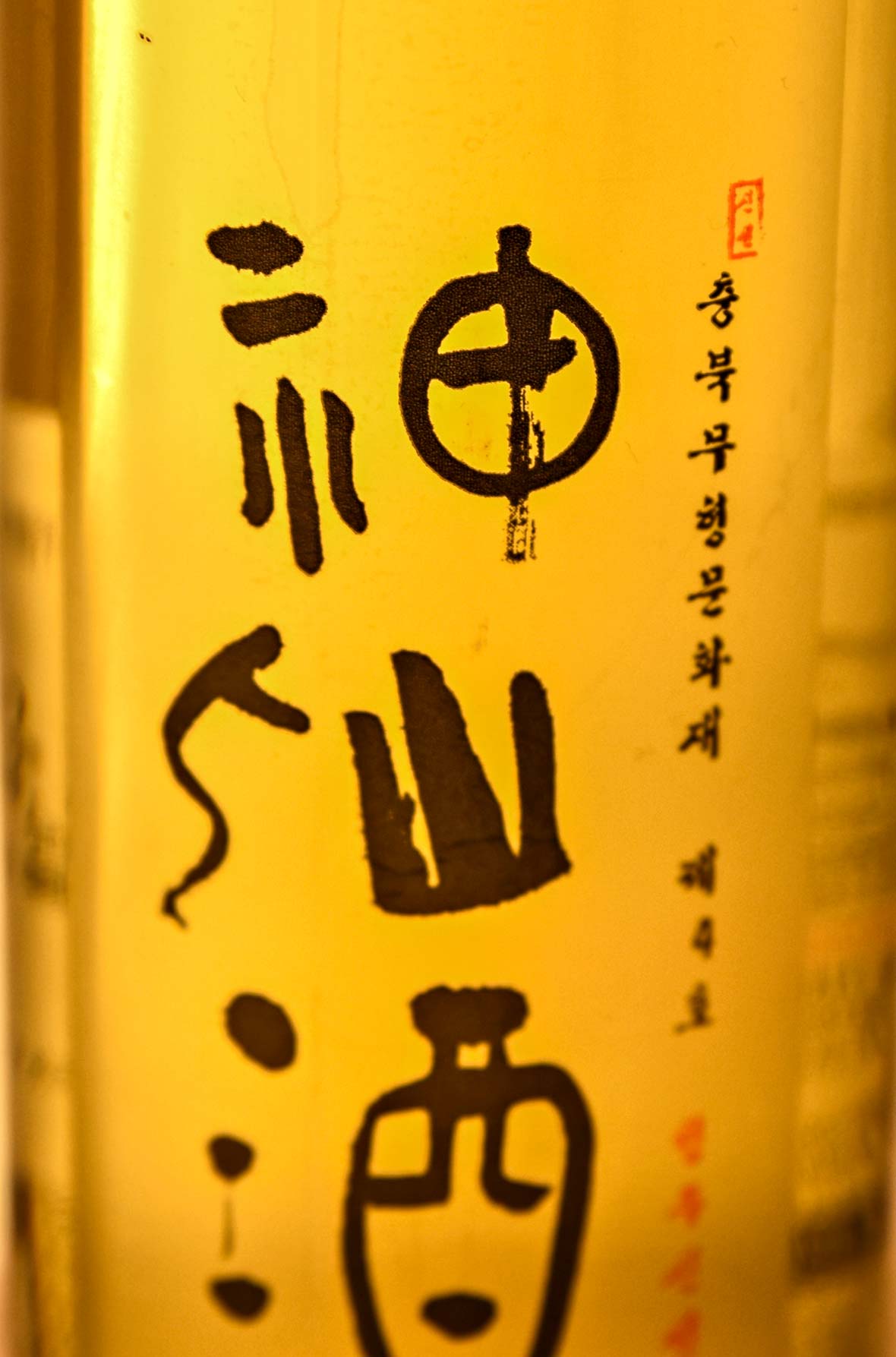

Just before the pandemic began, I found myself in Seoul staring at shelves lined with more than 100 Korean liquors, which mostly shared a lineage. Yet you wouldn’t have thought so. Some were clear as vodka. Others looked like milk, brandy, whiskey, white wine, or cloudy apple juice. Collectively they’re known as sool, which in Korea refers to liquor but historically was the term specific to fermented rice alcohols.

I was in the Sool Gallery, a part museum, part shop, and part tourist attraction run by the South Korea Government to promote the country’s traditional liquors. This facility in Gangnam district closed during the pandemic. Recently, however, it’s reopened in a more tourist-friendly location, near the entrance to Seoul’s biggest attraction, the giant 14th-century Gyeongbokgung Palace. There, it offers a range of experiences.

Visitors to Sool Gallery can peruse one of the city’s largest collections of rice alcohols, all of which are available for purchase. If they’re unsure which of these drinks best suits them, Sool Gallery staff can explain the attributes of different varieties. This facility also provides taste tests. By contacting the Sool Gallery website (www.thesool.com/eng), tourists can organize an English language taste test or a workshop on the distillation of these liquors. Those latter sessions, normally conducted in the Korean language, also delve into the history of sool.

The Sool Gallery has a particular focus on the king of Korean rice drinks, Soju. This type of alcohol is so popular it even helped tackle COVID-19, with many Soju distillers pivoting to making hand sanitizer in 2020. Soju is one of the world’s most popular liquors, in terms of volume drunk and the number of countries in which it is sold (more than 100).

While not globally renowned as big drinkers, a 2019 study by Euromonitor International found that South Koreans were among the world’s heaviest consumers of spirits, per capita. Soju was drunk twice a week by about 30% of adult South Koreans, they reported. That’s without even considering the consumption of soju’s sibling drinks Makgeolli, Takju, and Yakju.

Soju was the original sool. The variety of rice alcohol now produced in South Korea is, to a large extent, the result of prohibition. To try to protect its limited rice stocks in the 1960s, the South Korea Government banned soju. This law remained until the 1990s. As you can imagine, the demand for sool created a brisk black market in illegal liquors, which some outlaws distilled using different ingredients, like barley, wheat, and tapioca.

This helped sool to evolve. Then when the ban ended, it ushered in an era of innovation, with distillers using numerous ingredients and flavors. Yet sool remains strongly linked to its earliest versions, which landed in Korea in the 13th century via the invading Mongols. This is explained in Soju: A Global History, the definitive account of this liquor written by Hyunhee Park, a history professor from the City University of New York.

Professor Park wrote that in the 13th century the Mongols popularized the distillation of alcohol in Korea, which was a domain of the Mongolian empire at that stage. Sool developed out of arak, a variety of Mongolian spirits. Gradually, it became South Korea’s chief party starter.

Soju, Takju, Yakju, and Makgeolli can be distilled side by side. The initial, cloudy strain of liquid is Takju, which can then be diluted with water to create Makgeolli. The follow-up strain provides clearer and more potent Yakju and further distillation results in Soju.

While sool distillers now experiment with flavors – from strawberry to cinnamon and pineapple – some things have remained the same. Sool etiquette is old school. Tourists are not expected to understand these ancient customs. But for South Koreans it is a faux pas not to dispense and drink rice alcohol appropriately. Here’s how to do sool correctly.

Firstly, in a social situation – sool is commonly consumed in communal settings – the oldest person should dole out the first drink. You should not pour sool into your glass, unless you’re alone. Let others serve as you do for them. And be sure to hold the glass in both hands as they pour.

That’s it. These are basic rules which will please and impress your South Korean hosts. After all, you’re not just downing alcohol. You’re drinking eight centuries of history, tradition, and innovation, all infused with the murderous influence of the Mongols.