The millennial vibes are strong as I take a stroll down Dang Thai Mai street in Hanoi’s leafy Tay Ho area. An emerging star in one of the hippest hoods in Vietnam’s ancient capital, the street balances age-old tradition with an understated — but clearly detectable — current of youthful energy.

With the early-evening twilight casting a romantic glow on proceedings, young couples ride pillion on their Vespas to nearby Tay Ho (West Lake) – the largest of the city’s many lakes – whispering sweet nothings to each other as they participate in the time-honoured Vietnamese tradition of di choi, roughly translated as “hanging out”.

The spate of new businesses that line the street, too, have a dynamism in keeping with Hanoi’s status as the country’s capital of understated cool. At the Bottle Shop, Vietnam’s booming craft beer scene is showcased via the city’s strongest selection of local and international craft brews, ciders and spirits.

Close by, Turtle Lake Brewing Company doubles down on the craft booze theme – serving a wide variety of bottles. Just along the street at Bao Wow, meanwhile, chef Phan Nhu Long and his partner Katie Taylor are attending to a packed house of diners, hooked on their delicious Taiwanese baos.

The couple have only been operating their venture at the current premises since earlier in 2018, having piloted the concept successfully in pop-up form at music festivals and flea markets around Hanoi. And it is this “can-do” sense of possibility that is helping transform the once-conservative grand dame of Indochina into such a lively old lady.

Hanoi feels like on the most creative cities in southeast Asia. I love it.

Ian Paynton, the founder of Hanoi-based creative agency.

“Hanoi feels like on the most creative cities in southeast Asia. I love it,” agrees Ian Paynton, the English founder of Hanoi-based creative agency We Create Content, as we work our way through a Fun Guy (teriyaki mushroom, Asian slaw, house pickles, coriander and radish) and a fried chicken bao. “It’s so soulful and there’s inspiration to be found everywhere; in the way people tackle daily problems, the retro Vietnamese typography, the colours of the crumbling buildings and among the city’s creatives.

“Living costs are still relatively low, which gives artists, writers, photographers and designers the space they need to work on personal projects. I think that’s when some of the best work can happen. It seemed to me like the perfect environment to set up a creative agency that services the region.”

I see plenty of evidence to back up Paynton’s fervour during my time in Hanoi. Breakneck development has only partially diluted Hanoi’s intrinsic charm, and it’s hard not to be won over by the city’s charismatic tapestry of lakes, temples and street scenes.

As well as gleaning inspiration from the past, I immerse in Hanoi’s modern vitality – a stew brought to bubbling point by creatives and entrepreneurs from Vietnam and overseas. Over the course of the weekend, I browse contemporary art galleries such as Manzi, sip cold-brew coffees and kick back with a book at Tranquil Books and Café and see the nights out with live shows and DJ sets at venues such as Hanoi Rock City and Savage.

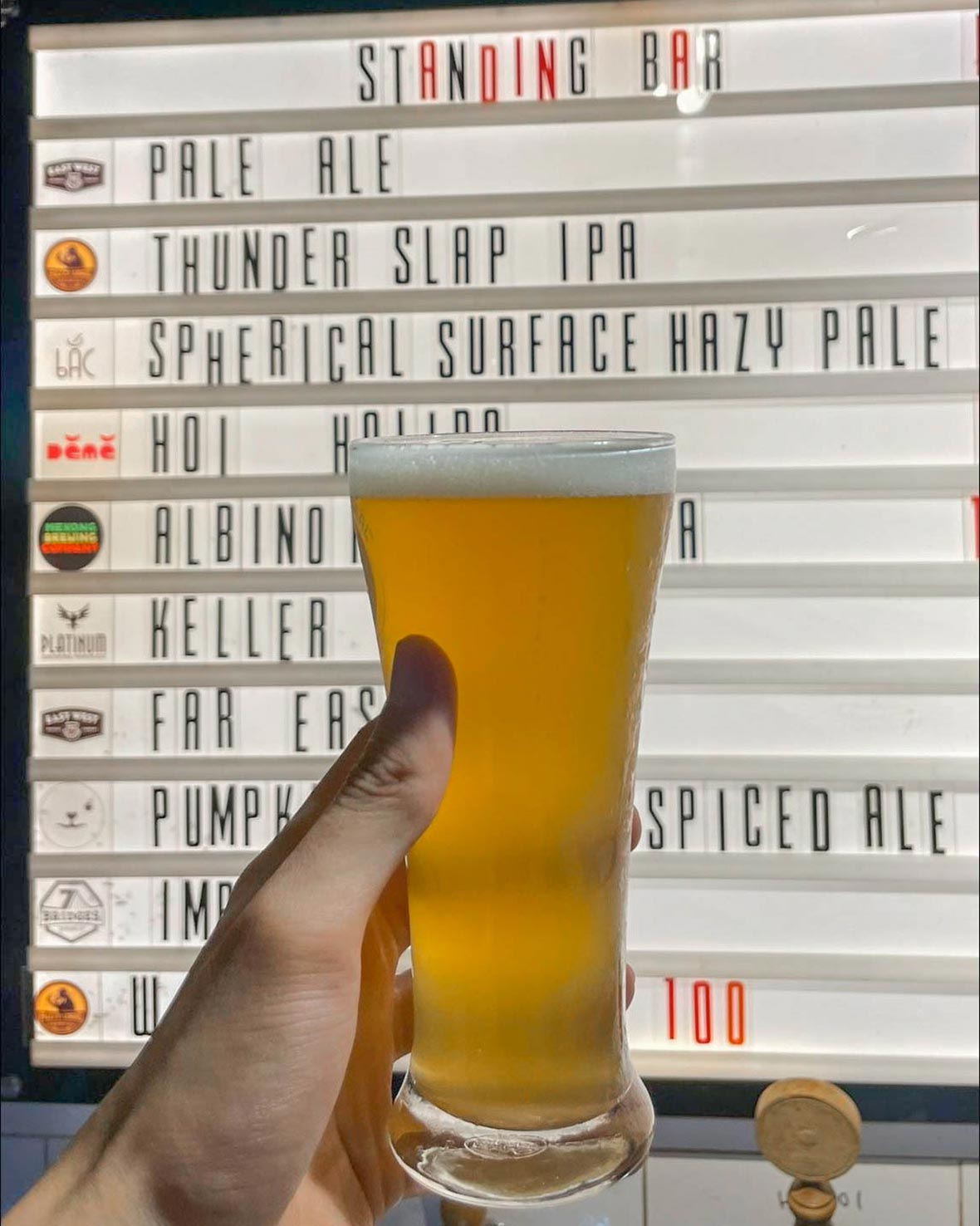

One evening, I adjourn to Truc Bac Lake and another of the city’s hip new gathering points, Standing Bar, to speak to co-owner Giles Cooper. Cooper, a lawyer from New Zealand, who has been based in Hanoi since 1999. When Cooper arrived, Hanoi was a very different beast than it is today. Although Vietnam was in the process of opening its economy after years in the international cold, the capital – as the seat of the ruling Communist Party and the vanguard of Vietnamese nationalism – was still a rather insular place, with few foreigners and little in the way of contemporary music, art or food and beverage options.

“There’s been a few changes since then,” he jokes over a glass of IPA from Ho Chi Minh City-based brewers Heart of Darkness – one of 19 beers on offer in Standing Bar’s impressive tap room. “Having said that, I don’t think that anything has intrinsically shifted. When I arrived, there were less foreigners in Hanoi, but it was still a cool place. Now, there are more foreigners here, and more Vietnamese coming back from overseas so there are more different ideas and viewpoints being thrown into the mix, which can only be a good thing.”

Of course, modern Hanoi is not just about creative agencies, left-field art venues, tucked-away bars, and cutting-edge restaurants. Ho Chi Minh City may have witnessed more breakneck development but there’s cash aplenty in the capital these days – I witness at least six Bentleys negotiating through the swarm of motorbikes on my first day alone – which means that bohemian doesn’t equate to basic.

Indeed, my hotel, the Sofitel Metropole, is a fine example of this. Built by the French in 1901, the Metropole was described, with typical Gallic fanfare, on opening as the ‘largest and best appointed hotel in Indo-China’.

Previous patrons include louche, creative icons like Somerset Maugham, Graham Greene and Charlie Chaplin. Folk singer and anti-war activist Joan Baez, meanwhile, is believed to have hunkered down in the hotel’s “secret bunker” during an American bombing raid in 1972.

While the Metropole is steeped in over a century’s worth of history, its near neighbour – Tadioto – is an icon of the city’s recent creative renaissance. For a final insight into Hanoi life, I saunter across the tree-lined boulevard to the venue (which serves variously as a bar/cafe, event space, and as a meeting spot for arty types of all stripes) to meet owner Nguyen Qui Duc.

Duc, a memoirist, poet, scriptwriter, translator, former on-air personality for US National Public Radio and the son of the highest South Vietnamese official ever imprisoned by the North, is regarded as a figurehead of the Hanoi scene: largely due to his own conviviality and uncanny ability to create spaces conducive to creative ferment.

Tadioto has been around in various incarnations since 2006, but has now been a fixture in its current location since 2014. Despite its air of relative permanence, though, it retains a freewheeling ethos that, once again, encapsulates the spirit of new Hanoi.

“Everyone supports each other here,” says Duc, while doling out generous pours from yet another bottle of red Bordeaux. “It’s like a village. A village with six million people.”