Stones the size of large animals often rumble down the hillsides here, there are no guardrails, and the wreckage of vehicles that have gone over the edge dot the hillsides, making me pay far more attention to the moment than I’d prefer.

From the front seat of my jeep as our driver navigates us over the snowbound Khardung La, the old adage that “the journey is more important than the destination” has never been more apt. In the rarified air, higher up here than most of the world’s mountain tops, everything seems to be in slow motion, which I suppose is a good thing, in that we have no chains on the tires and the road is an ice-covered slide that snakes down into the valley below.

I’m making the journey from Ladakh’s capital, Leh, into the Nubra Valley, an elongated valley that cuts between the mighty Karakoram Mountains and the Ladakh Range, and features some of the kingdom’s most stunning attractions, from serrated peaks and wild glacial rivers to some of the most mesmerizing alpine lakes in the world, to sects of Tibetan monks that don masks and colorful hats and engage in trance-like dances around the courtyards of their monasteries.

ABOVE: Khardung La.

The Nubra was closed to the outside world for years, as it sits smack against the Chinese and Pakistan borders and its icebound mountainous terrain has been the site of the world’s highest military conflict (an ongoing dispute with Pakistan on the Siachen Glacier) and endless territorial skirmishes between all the countries involved. The Indian military requires travel permits and plenty of red tape to get here, although this has recently been more relaxed as cease fires have held in place for over a decade now and the region has become stable.

Add to this obstacle list the terrain: Ladakh means “land of high passes,” and nowhere is this more apt than crossing to the Nubra. The main route in, over the Khardung La, is claimed by India to be the “world’s highest motorable road,” although recent measurements showed that the signs at the top proclaiming the pass to be 5600 meters were in error, and that the pass is just a mere 5359 meters (17,582 feet), surpassed not only by a road in Bolivia, but by yet another road recently built by the Indian border roads organization further on.

ABOVE: Costumed monks dancing at the Diskit Gustor Festival.

The Khardung La along with the neighboring Chang La in Ladakh are both outrageously high. Indian army tents with emergency oxygen sit just off the summits, often needed to bail out tourists that haven’t acclimatized properly in Leh before setting off, and permanent teams of road workers huddle up here in the freezing temperatures, trying to keep the roads clear year-round of snow, rockfall, and in passable shape for those trying to reach Ladakh’s most isolated corner.

We inch our way down the pass towards the confluence of the Shyok and Nubra rivers. Coming from Tibet, the turquoise glacial-fed waterways meet at the center of the Nubra Valley, providing an irrigation source in an otherwise barren and inhospitable land, resulting in beautiful patchwork quilt fields of wheat and barley that cover the oasis-like villages that are strung out here. It’s late September, and the rows of poplar trees are turning yellow, striking a vivid contrast to the brown mountains and high desert monochromes.

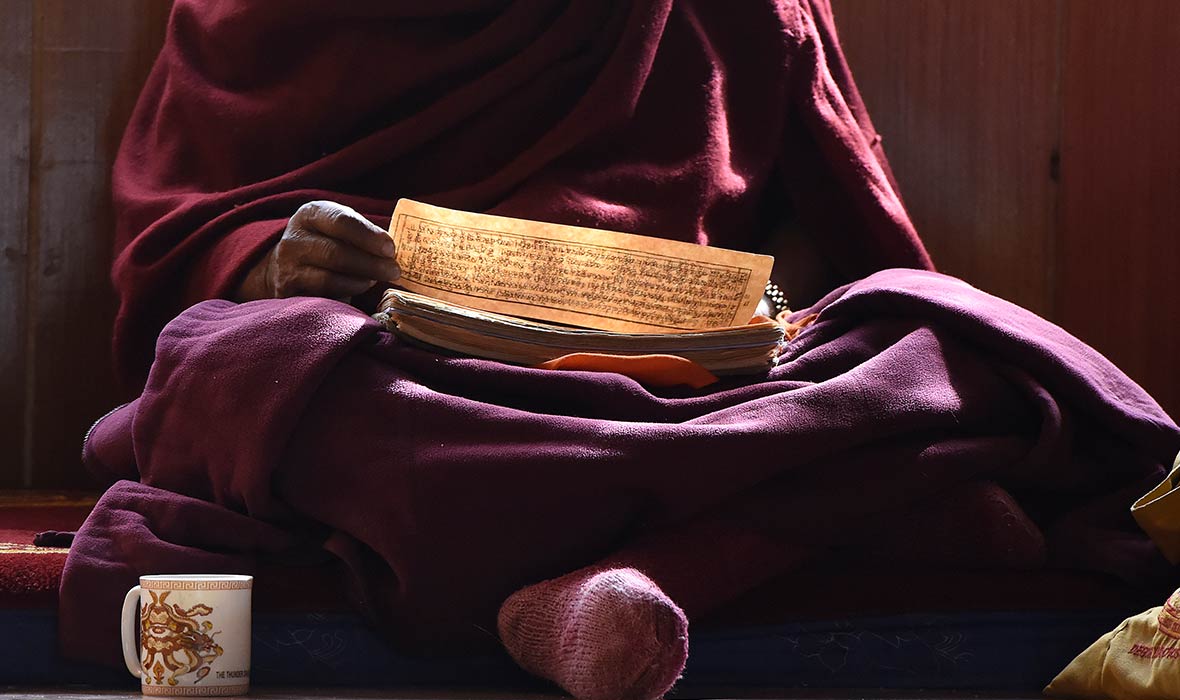

ABOVE: Monk reading scripture inside a Diskit gompa.

As we pass the main Nubra settlements of Diskit and Hundar, sand dunes stretch across the road. It’s a bit hard to fathom, the thought of a desert set at 5,000 meters, and even harder to grasp the fact that I’m seeing Bactrian camels wandering across the dunes here. In fact, camel and yak caravans were common here prior to the Chinese sealing the border at the end of the 1950s. The animals were used to transport spices, wool, silk, and other goods for trading on what was once the most hazardous trans-Himalayan routes of the fabled Silk Road, bringing good from China through to Pakistan, Central Asia, and beyond.

Today, tourism is the economic lifeline of the Nubra, and my jeep mates and I get to witness this firsthand, stopping for the evening to enjoy a sky full of stars in a stylish desert camp, heading out for a short camel trek as the sun goes down. Tsering, the owner of our camp, says that business is booming, with plenty of Indian tourists now coming to discover the country’s most northern fringes. Making a pilgrimage to Ladakh on a motorcycle has also become a sort of bucket list challenge, and indeed, the majority of our “glaming” companions tonight have arrived on overloaded classic Indian Enfield bikes.

ABOVE: Camels of Nubra Valley.

In the morning, we arise early and head over to Diskit Gompa, a monastery that perches on a hillside overlooking the heart of the Ladakh’s Nubra. Home to the Gelugpa “yellow hat” sect of Tibetan Buddhism (the same one that the Dalai Lama belongs to), this is the largest monastery in the valley, and its scenic location draws plenty of visitors. However today, scores of pilgrims are making their way here to see the Diskit Gustor, an annual festival marking the triumph of good over evil , in which the resident monks put on elaborate masks and costumes and proceed to dance hypnotic “chaam” dances, in which they twirl in a form of meditation in the monastery courtyard, and re-enact scenes from the literature of Padmasambhava, a 8th century teacher and Tantric Buddhist master also known as Guru Rinpoche.

The festival lasts for 48 hours, and although travelers make the tough journey from Leh specifically to see the celebrations, it is performed solely to the whims of the monks. They decide how many dances are needed for the day, and don’t have any fixed starting times. While neighboring Tibetan Buddhist countries such as Nepal and Bhutan also hold chaam dances, they are often done to large tourist crowds, whereas here in Nubra, there are twice as many local monks watching the proceedings as there are outsiders. We sit in silence, with the only sound breaking the peace being blasts from elongated Tibetan horns and conch shell trumpets played by the monks. Meanwhile, their brethren emerge from the gompa wearing psychedelic colored aprons, sombrero-like hats, and thick felt shoes, twirling in rhythm as they gaze upwards.

The monks disappear into the monastery, only to come back out donning gaily colored paper mache masks that depict various demons. Shuddering in the high-altitude air, I’m struck by how phantasmagorical this scene appears, and I pinch myself to ensure that it is real and not some illusion created by the lack of oxygen.

ABOVE: Turtuk, a Balti village at the end of the Nubra.

From Ladakh’s Diskit we travel north through the Nubra. The road here has been recently paved by the army and road corps, but the permanently unstable terrain ensures that many sections are either washed out, covered in stones, or just returned to their dirt track state. As we approach the Pakistan border, the valley narrows and the Karakoram peaks become more jagged and foreboding, looming high above the valley floor. This section of the Nubra was only recently opened to tourism, and is home to one of India’s most unique villages, Turtuk.

Turtuk is a Balti settlement, where villagers speak Balti language, practice Shia Islam, and where men still wear the traditional shalwar kameez and Balti caps, while the women are covered and wear embroidered print dresses. In fact, Turtuk was part of Pakistan’s Baltistan region until 1971, when Indian forces took it over during the border war, and then never returned it. Villagers who were out working elsewhere or visiting friends or relatives that day remained in Pakistan, many of whom have never come back, while Turtuk has become Indian, at least on paper and in passports.

ABOVE: A traditional Balti man in the store alleys of Turtuk.

It’s a fascinating village, home to some of the most elaborately built stone irrigation channels in the world, and everything here is constructed from rock, from the homes built over cobblestone alleys to even cold storage systems created for perishables during the warm summer months. Some of the world’s highest mountains, from K2 to Masherbrum, and Broad Peak are all less than 100 kilometers from here, yet separated by the sealed border and impenetrable mountain walls.

Spending an overnight in the village, I’m struck by how industrious the Turtuk Baltis are in contrast to the more laid-back Ladakhis. From the labor-intensive buckwheat fields and row upon row of apricot trees, there is non-stop agricultural activity going on here, all the more amazing considering that the village feels so completely hemmed in, both by the fierce serrated peaks that surround it, the uncontrollable raging river and steep rock avalanche slopes above, and by the border, just a few kilometers down the road.

ABOVE: Pangong Tso.

Unable to continue further, we turn around and retrace our steps. Yet we are far from finished, as the Nubra has been saving the best for last. We follow the Shyok back through Diskit, and then across crumbling unstable rock slopes, where the road meanders up above the valley and then returns to the flood plain below once safe. Heading south now, we are skirting another disputed border area, the Aksai Chin, where the Chinese and Indians have argued over a wildly rugged swathe of mountains and high altitude plain, home to Tibetan wild ass, snow leopards, and other rarely seen wildlife. These days, relations over the line of control here are calm, and tourists can pass through on their way to the Nubra’s crown jewel, the incredible alpine lake of Pangong Tso.

ABOVE: Fall colors at the Merak village.

Set at 4,300 meters, Pangong Tso of Ladakh meanders 135 kilometers through both China and India, with access to foreigners only possible on the Indian side. Surrounded by mountains on all sides, the lake is spectacular, changing colors throughout the day and season, from deep blue to emerald, and every shade in-between. Despite no longer having an outlet and being highly saline, the lake still completely freezes over during the long winters, during which time villagers actually cross it and make forays into the mountains to gather supplies of wood for heating.

Our driver brings us as far as we are legally allowed to go along the Indian side of Pangong, to Meerak, a small village set on the banks of the lake. Autumn is in full swing here, with the village bathed in golden yellow colors. Above, snow clad mountains surround, and then there is the lake, still, deep, and hypnotic. Walking around the village, I’m immersed in a rural fairy tale. Ladakhi farmers tend to their fields, and several villagers walk around the dusty paths set between rows of poplars and willows, spinning prayer wheels as they go and reciting Tibetan mantras. They nod at me, smile, and say “Julay,” the all-inclusive Ladakhi word for hello, goodbye, and thank you.

The owner of our homestay we are staying at, Tenzin, turns out to be more than just a hotelier. He is actually a respected medicine man, just returned from being invited to various villages in the region to give blessings. He speaks decent English, and he is constantly smiling. His father, a wizened sunburnt man comes in to join us, bringing with him a large jug of chang, the local fermented millet beer, which he insists on passing around, all the while spinning his prayer wheel and beaming. I ask Tenzin why he and his father always appear so happy, and he grins and says, “Life used to be really hard here. We were cut off from the outside for four to five months of the year, we had no electricity, there were no mobile phones, and the roads here were terrible. Now we have almost year-round road access from Leh, we have some hours of power, and we are able to meet visitors from around the world and share with them. What’s not to be happy about?”

I reflect on how arduous the journey has been for me to get here in these good times, and try to imagine how much harder it must have been, and how incredibly hearty all of the inhabitants of the Nubra must be, both then and now. Tenzin’s father refills my glass, and he toasts our visit. And almost as if reading my mind, says, “Enjoy the journey tomorrow, every minute of it.”

Yes, in the Nubra Valley, it’s only about the journey itself, and the destination is just a sum of the parts.