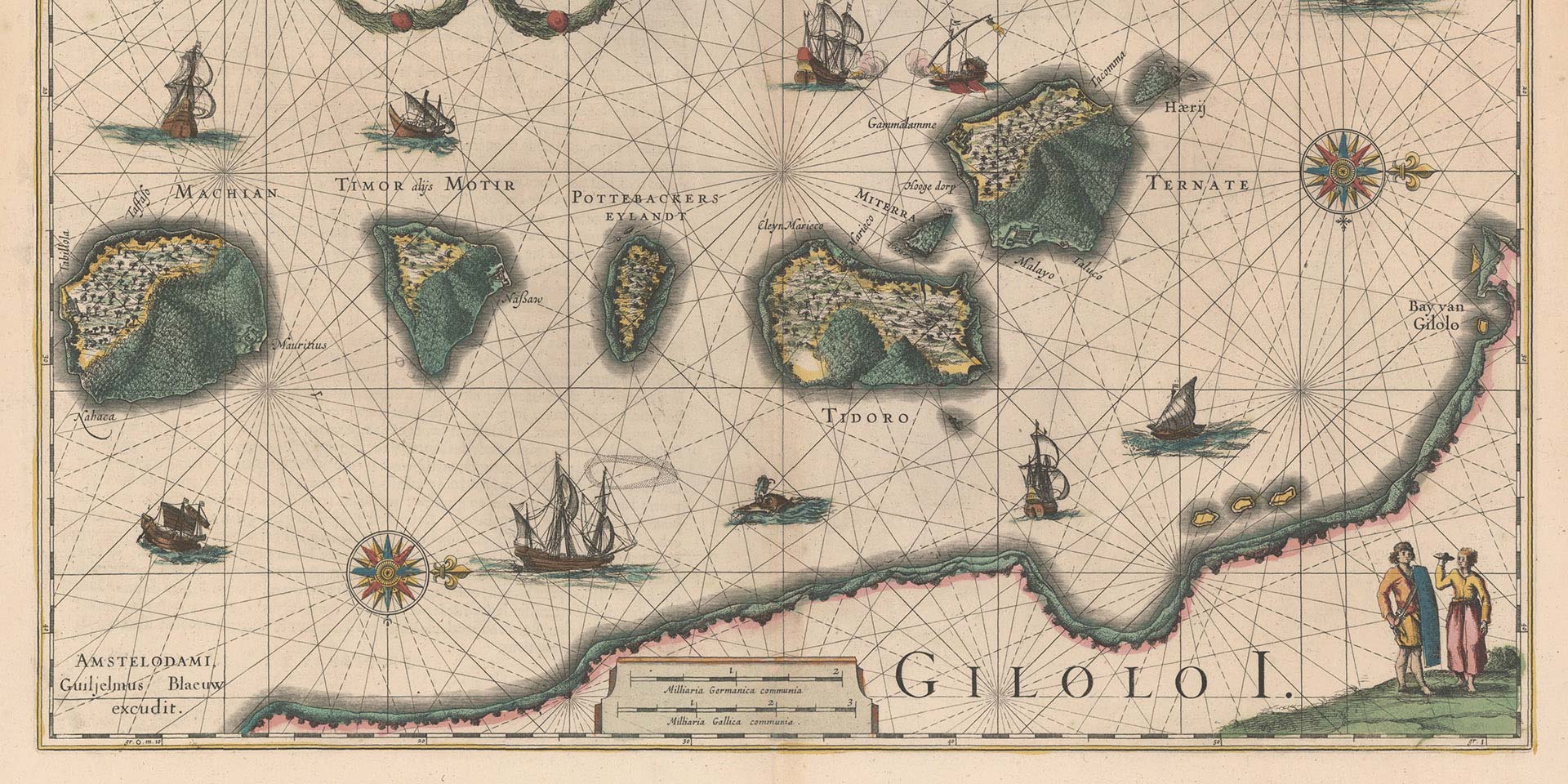

What is today a travel hotspot for East Indonesia travelers and cruise-takers, the Maluku once defined the Southeast Asia spice trade. Ternate is a small volcanic island off the coast of the larger Halmahera in Northeast Indonesia. It was favored for the clove trees, sought throughout Asia and Europe as a condiment and medicine; Europeans even believed clove oil could ward off the plague.

The territory under the suzerainty of Ternate, and its nearby rival Tidore, stretched to Papua in the east and beyond Ambon in the south, an area known as Maluku, and the sultanates of Ternate and Tidore, which converted to islam in the 15th century, were the center of the Malukan world. The balance of power between them was believed to keep their world healthy. From the fourteenth century onward Arab, Javanese, and Chinese traders came across the seas in increasing numbers to trade with the two wealthy islands.

ABOVE: Laguna Lake at Ternate.

In 1512 Portuguese explorer Francisco Serrão was the first European to reach Ternate, an important event as Europeans had been desperate for direct access to the fabled ‘Spice Islands’. The land route to Europe was mainly under Muslim control, so by the time spices reached Spain and Portugal they had passed through many hands and become prohibitively expensive.

Capturing the Malay city state of Malacca in 1511, the Portuguese had a good base in Southeast Asia. Serrão initially aimed to get nutmeg from the Banda Islands in Southern Maluku, and he achieved this, but not before he and his men were shipwrecked. Having lost his boat, he departed Banda on a Chinese junk, but was once again marooned, this time on a small island near Seram. They were rescued by locals and taken to Ambon.

From there news of the Portuguese advanced weapons and armour reached Sultan Abu Lais and Serrão was invited to visit Ternate. He became an advisor to the Sultan and made no attempt to return to Malacca. Serrão died in 1516, at around the same time as his more famous cousin, Magellan, who perished not far to the north, in the Philippines. It was members of Magellan’s crew, not the captain himself, who made the first circumnavigation of the globe.

ABOVE: Fort Tolukko.

In 1522 the Sultan allowed the Portuguese to build a fort on Ternate and start buying cloves. Most of what we know of the Portuguese presence there, and about the Malukans themselves, comes from the account of Antonio Galvão, Portuguese Governor of Ternate from 1536 to 1540. A fascinating anecdote in Galvão’s “ A Treatise on the Moluccas” is that the Malukans believed their sultans and rajas (kings) were descended from humans hatched from four serpent eggs. In ancient times a prominent Malukan elder spotted a beautiful clump of rattan from his kora-kora outrigger. He went ashore to investigate and in doing so came across the eggs. The legend has it that the time before the kings had been complete chaos.

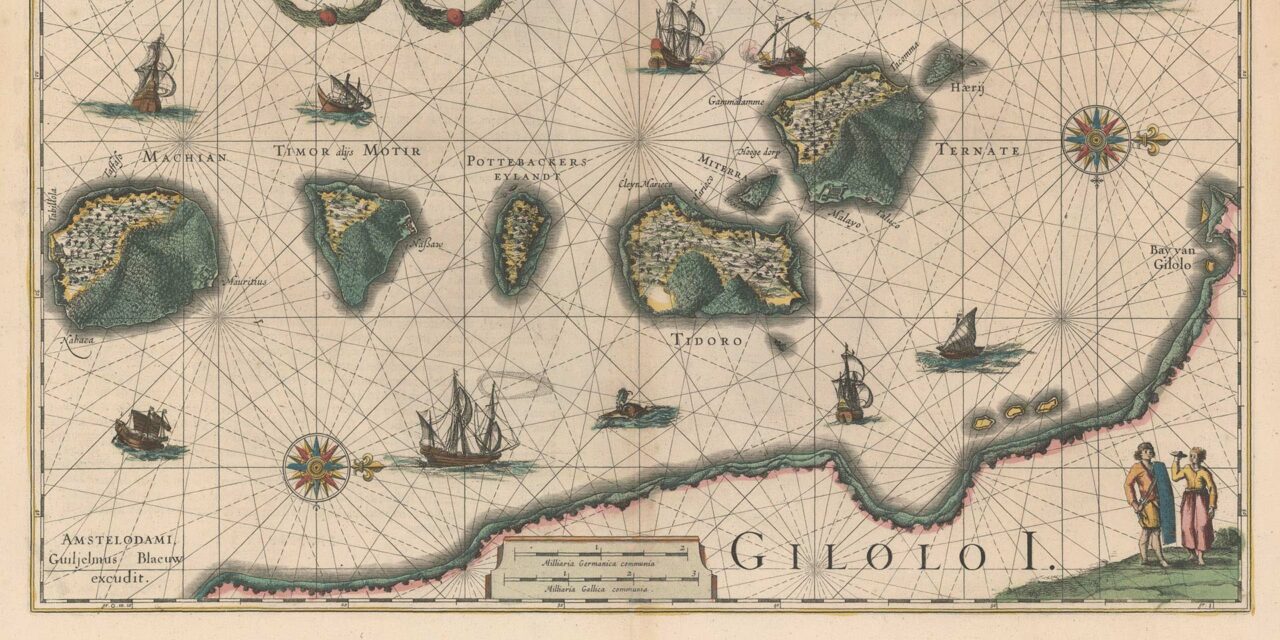

ABOVE: Portuguese Governor Mesquita stabbing Sultan Hairun in the back.

The relationship between the Portuguese and the Sultan of Ternate was never free intrigue and violence. Tensions arose as the Portuguese wanted the Malukans to sell cloves exclusively to them, and also due to the activities of Jesuit missionaries looking for converts. In 1570 Portuguese Governor Mesquita literally stabbed Sultan Hairun in the back.

The new Sultan, Hairun’s son Babullah, laid siege to the Portuguese fort and eventually the Portuguese left for good in 1575. A monument to this victory can be found at the ruins of Fort Kastela, it features scenes of the betrayal of Hairun and ensuing battle. Babullah, who retook control of the spice trade, is regarded as a hero in Maluku. The Portuguese were never again a strong force in the region, but ultimately reappeared, this time on Tidore.

ABOVE: A view of Tidore.

With the Portuguese vanquished the Spanish set up on Ternate in 1606. Their status was never secure, and 1663 they gave up, heading back up to the Philippines. However, Maluku was not left alone for long, the Dutch East Indies Company (VOC) arrived with more determination than the Portuguese or the Spanish. To monopolize the clove trade, the Dutch forced the Malukans to destroy all the clove trees and only allowed trees on a few select plantations under VOC control. On the Banda Islands things were even worse, as the Dutch nearly wiped the locals out in enforcing their monopoly on nutmeg. In 1770 the monopoly on cloves was broken as a French missionary smuggled seeds from a hidden tree on Ternate. By the nineteenth the spice trade had lost importance and Maluku fell into obscurity as a far flung province of the Dutch East Indies.

Ternate is also famous for the essay that British naturalist Arthur Russel Wallace wrote there. Wallace had come up with the basics of evolution, including natural selection and sent his essay to Charles Darwin. Realising that he wasn’t the only one working on the theory of evolution was a catalyst for Darwin publishing his own writing. Wallace’s “Malay Archipelago” is a much more engaging book of nineteenth century natural science than Darwin’s “Origin of Species”.

ABOVE: Gamalama volcano.

Today the volcanic peaks of both Ternate and Tidore provide a good challenge and great views for climbers. Ternate’s Gamalama volcano is active and sulphur steams from its crater. Tidore’s Kie Matubu is beautifully symmetrical and is featured on Indonesia’s one thousand rupiah note. While in the coastal cities life is similar to the rest of modern Indonesia, the mountain villages, notably Moya on Ternate and Gurabunga on Tidore, give a glimpse of times past.

On the steep slopes local men wielding machetes harvest cloves, nutmeg and durian. Red mace and cloves are left on the roadside to dry in the sun. Cloves are still in demand in Indonesia as they are used in the ever popular kretek cigarettes. On all the inhabited islands of the Indonesian Archipelago the sweet smell of kretek smoke is never far away.

Both islands have multiple ruined European forts worth visiting. Another highlight are the kratons, or palaces of the sultans. The British designed Ternate Kraton is fascinating, especially the small museum inside which has portraits of various sultans, old maps and sixteenth century Portuguese armour. Visiting these islands offers an insight into the enduring nature of the Malukan Sultanates and also the power struggles of an early era of international trade.