Ramshackle, wooden huts are set up along the shoreline and palm trees sway in the breeze as men cut into coconuts with machetes on the sands. My camera and I arrive via small wooden raft from the outrigger boat that brought me from Coron Town; as I set foot on an island that few other travelers have had the chance to see, I am greeted with a fresh coconut by members of the Tagbanua tribe.

You won’t find this beach on any maps, and my guide, Aldrich, who has been working to develop sustainable tourism amongst the Tagbanua that have called the islands of Coron home for thousands of years, won’t give me its name. The locals want to limit the number of visitors journeying here, because, for them, this is sacred land and the Tagbanua are its guardians.

Around the huts, locals dress in a mixture of traditional clothing and Western garb picked up in the markets in town. Some of the men have woven square shields, while makeshift wooden spears rest against the towering limestone karsts that overshadow the beach. The boys ready their drums while another man practices on a hand carved, bamboo flute.

The Tagbanua live on this beach in Coron Island, but it’s far away from the well-known tourist sites such as Kayangan Lake and Twin Lagoons. For this occasion, a cultural display for myself and a few other travelers who are visiting; a few local families have invited their relatives from neighboring beaches too. They prepare for a traditional dance.

The First Humans in the Philippines

ABOVE: Tagbanua boy with a makeshift drum.

“The Tagbanua are the descendants of some of the oldest people to settle in the Philippines,” Aldrich explains while the islanders prepare. “Coron Island is their home, and they’ve lived here for thousands of years, but few people who visit the lakes and the lagoons realize that there are people living on these islands.”

The Tagbanua are thought to be related to the Tabon Man, a 16,500-year-old human skeleton that was discovered in a cave in Palawan. Until very recently, they remained isolated in these remote locations, with little contact with the Spanish colonists of the Philippines, the Americans, or the Filipino government until the 20th century, when Palawan and Coron began to see a huge wave of migration from around the country.

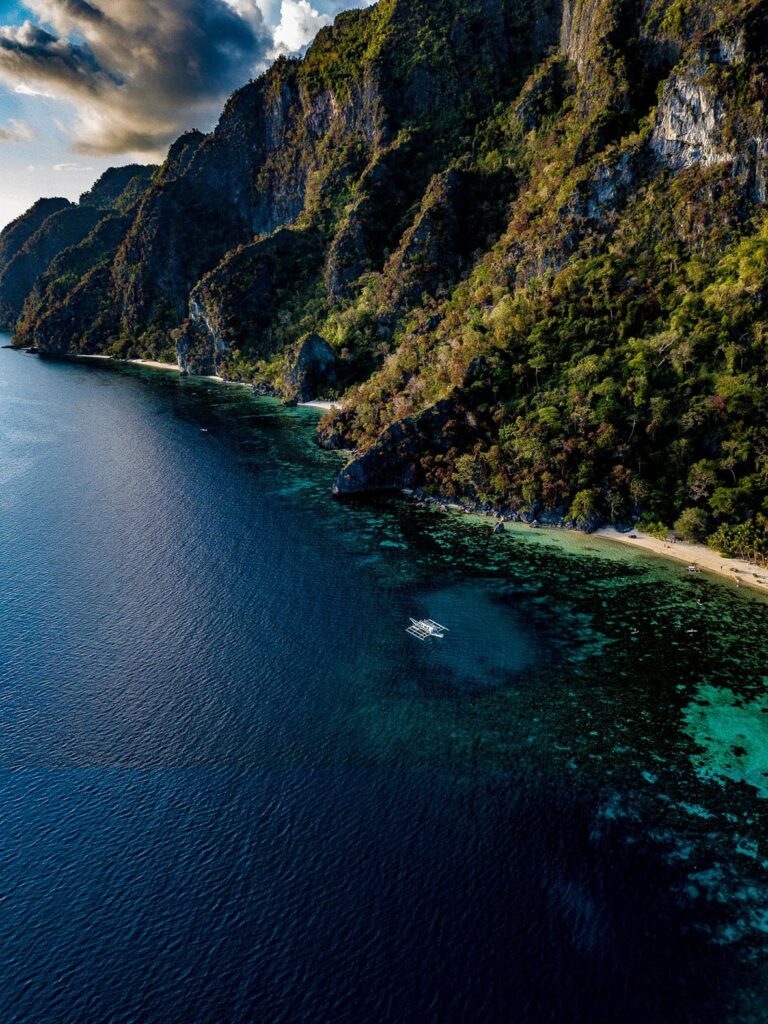

ABOVE: The island of the Tagbanua from the air.

With increasing tourism to Coron, the Tagbanua were eventually given ancestral domain over their own homeland by the government in the late 1990s, but as Aldrich notes, “most of the mass tourism that has come to Coron has kept them in the shadows.”

Life in the Shadows of Coron

ABOVE: Playing a flute during a courtship celebration.

“I think it’s important that when we come to visit these places that we also acknowledge the inhabitants,” says Aldrich as the locals prepare for a traditional dance performance on the sands.

Most visitors to Coron will hear little of the Tagbanua when they are island hopping around the main sights or scuba diving. To the Tagbanua, each of the beautiful lakes that draw in an ever increasing number of tourists each year has its own legend, and as guardians of their ancestral land, they have a duty to protect the visitors and to keep their land clean.

You will see the Tagbanua collecting rubbish at Kayangan Lake or sweeping the beaches clean, and while technically they own the land, they have in many cases been under pressure to lease it out to tourism companies who take most of the profit

ABOVE: Tagbanua man with a spear.

Traditionally a very shy people; they are hesitant to answer any questions while I’m on their beach. The Tagbanua are reluctant to open up more land, but with more and more tourists year on year, they may well have to. Aldrich hopes though that through small cultural interactions such as this, responsible tourism that includes the Tagbanua and their heritage will give them a chance to rise from the shadows.

Traditional Courtship Dance

ABOVE: The Tagbanua prepare for a courtship dance.

The performers are ready, and to the sound of beating drums and the melodic music of the flute player, two of the men, shields and spears in hand, square off to each other while an elder narrates a tale of heroism in the Tagbanua language.

This is not a war dance, as I’d first thought, but a courtship dance. As the two men battle on the sand, a woman dances to their side. They are fighting for her love and she is waiting to see who will prevail.

There are more contenders, and soon sand is flying as the beats of the drums increase dramatically to set the pace of these encounters. The elder women join the younger woman in dance too, and eventually, an elder calls a halt, and a man is ceremoniously picked as the winner.

For the next hour, more dances are performed on the beach, more courtship rituals and war dances too before the sun begins to set in a fiery blaze over Coron.

As I get ready to head back to the boat, Aldrich says that the dances performed here were sanctioned by the elders to showcase “just a little bit of their culture.”

“Ultimately, they want the world to get to know them a little bit better and to realize that Coron Island is their domain, but we are all still discovering the best way to do that,” Aldrich says.