Getting on a plane to Beijing? Looking for something to read besides guide books and boring histories of China? This capital of the People’s Republic is chock full of history – from Tiananmen to the Temple of Heaven – so check out these ten books to help you get a better understanding of Beijing before and after you land.

Emperor of China: Self-portrait of K’ang-Hsi

ABOVE: Portrait of the Kangxi Emperor.

It takes a certain kind of confidence to write somebody else’s autobiography, especially when that somebody is one of the most powerful monarchs in history. The Kangxi (to use the current method of transliterating the name) Emperor came to the throne in 1662 when he was just eight years old and ruled China for nearly six decades. During that time, he crushed rebellions, thwarted his enemies, and led his soldiers on long campaigns of conquest in the deserts and mountains of what is today western China, all the while establishing himself as a man of culture and a patron of scholarship. Jonathan Spence, one of the most widely read Western scholars of China, recreates the inner life of the Kangxi Emperor through careful reading of the emperor’s notes, letters, journals, and official edicts.

It’s an academic tour de force and essential for anyone looking to understand China’s imperial era. If you are looking for more palace intrigue, one of the Kangxi Emperor’s descendants wrote his own autobiography. Puyi, who reigned as a child emperor from 1908 until the end of the dynasty in 1912, wrote a memoir entitled From Emperor to Citizen: The Autobiography of Henry Pu-yi (Also published as The Last Manchu: The Autobiography of Henry Pu-yi, Last Emperor of China). Puyi’s story was also the basis of the 1987 movie The Last Emperor which featured several scenes filmed inside the Forbidden City.

Rickshaw Boy: A Novel

ABOVE: Lao She illustration.

Xiangzi (“Camel”) is a rickshaw puller in 1920s Beijing. He is energetic, honest, hardworking with dreams of someday earning enough money to buy his own rickshaw. But Beijing has other plans, and poor Xiangzi finds himself on the wrong end of soldiers and schemers. Lao She’s Rickshaw (translated by Howard Goldblatt) is a gritty look at a class of people who were taken for granted by well-to-do residents and visitors to Beijing at the time. Lao She is the pen name of Shu Qingchun who was born in Beijing in 1899. He became a teacher and moved to London in 1924 where he served as a professor of Chinese at the School of Oriental and African Studies. He returned to China in 1930. Through his novels, plays, and short stories, Lao She is to Beijing what James Joyce is to Dublin or William Faulkner to Mississippi. His writing is beloved in the city for capturing the rhythms and textures of Beijing in all of its warts and beauty. Sadly, Lao She committed suicide in 1966, an early victim of the Cultural Revolution that convulsed China during the last years of the Mao era. Lao She also wrote one of China’s earliest Science Fiction novels, the political allegory Cat Country, published in 1936.

Midnight in Peking: How the Murder of a Young Englishwoman Haunted the Last Days of Old China

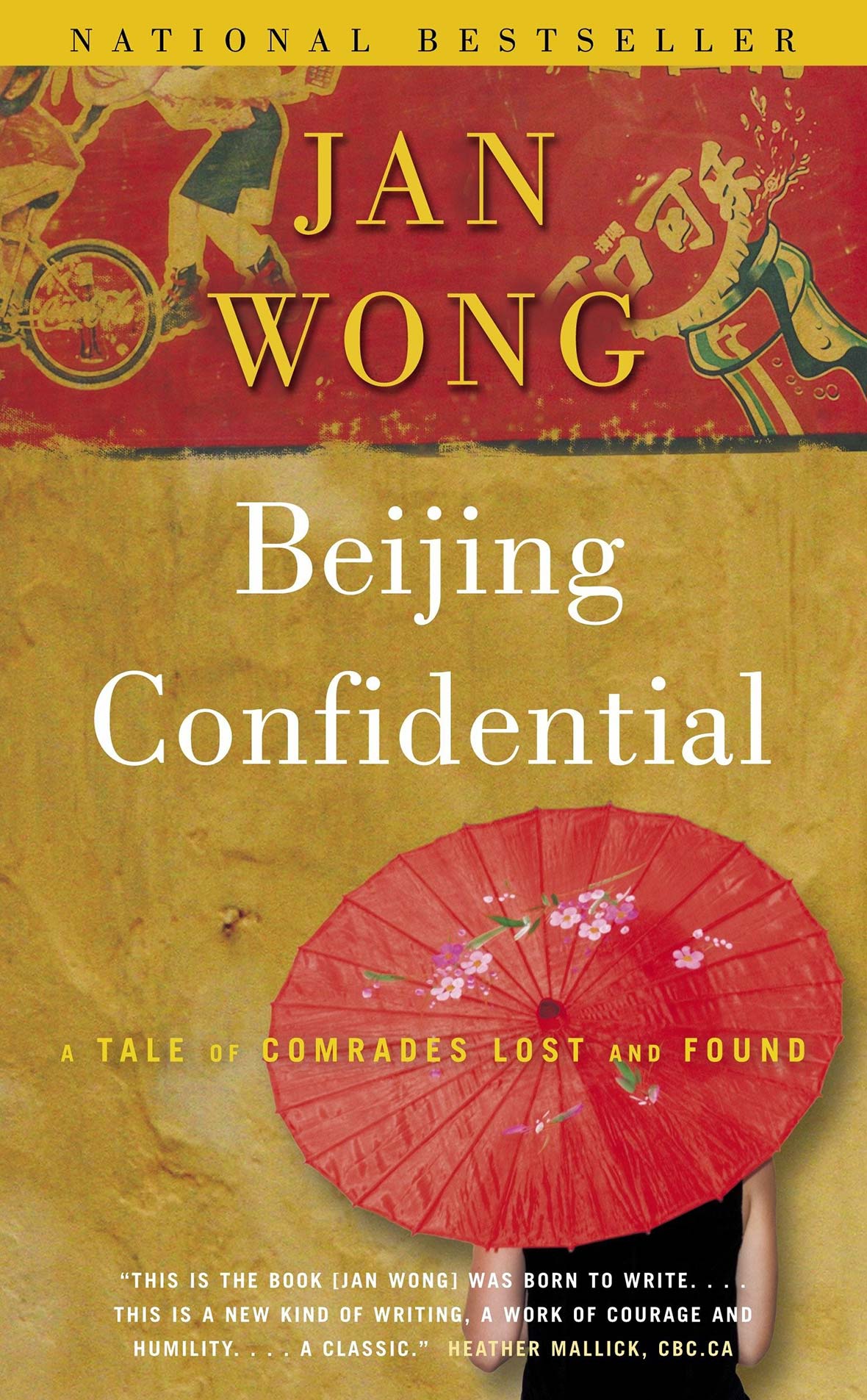

ABOVE: Image of the Japanese occupation of Beijing.

The year is 1937 and the body of a young woman is found in a ditch by the city wall. In Midnight in Peking, Paul French investigates the murder of Pamela Werner. In doing so, he takes the reader on a fascinating trip through the dark back alleys and glittering ballrooms of Peking between the wars. French uses newspaper articles, private correspondence, and archival research to recreate this world and introduces the reader to an eclectic assortment of characters: Pamela’s adopted father, the eccentric retired diplomat and scholar E.T.C. Werner; Chinese detective Colonel Han; and the Scotland Yard-trained Detective Chief Inspector Richard Dennis; as well as the less savory and more dangerous folks who inhabited the Peking demimonde known as the Badlands.

The mystery went unsolved, and Pamela’s murder was forgotten as the Japanese swept through North China later that year. Forgotten, that is, by everyone except E.T.C. Werner who made finding Pamela’s killer his primary task – some would say his obsession – for the rest of his life. Peking in the early 20th century was part Chinese city and part Casablanca – a place where White Russians, Japanese soldiers, British adventurers, American fugitives, and international diplomats lived, drank, and plotted. Few writers conjure this world with as much grit and style as Paul French while remaining as faithful as possible to his sources.

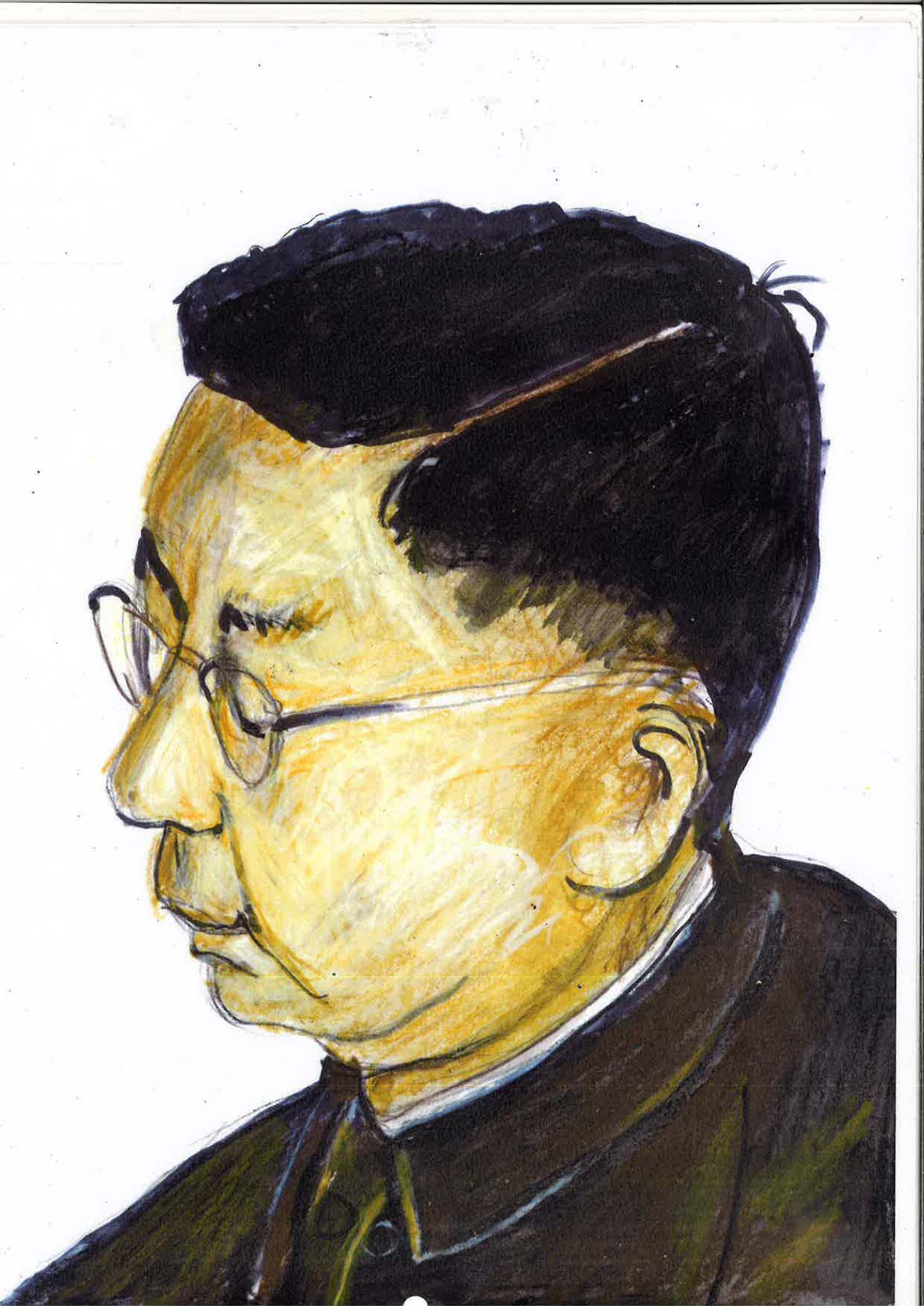

Beijing Confidential: A Tale of Comrades Lost and Found

ABOVE: Cover image of Jan Wong’s Beijing Confidential.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, Maoism was a faddish political theory on many North American campuses. In 1972, Jan Wong left McGill University and her native Canada to travel to China and enroll at Peking University. It was the height of the Cultural Revolution, and Wong was one of only a few international students studying at the university. While in Beijing, she met Chinese student Yin Luoyi, who asked Wong to help her escape to the West. Rather than offer assistance, Wong reported Yin to university authorities. Like millions of others, Wong eventually grew disillusioned with Maoism and would later go on to become a journalist, covering China for the Globe and Mail from 1988 until 1994. But her decision to inform on Yin Luoyi haunted Wong.

What had become of Yin? In Beijing Confidential: A Tale of Comrades Lost and Found, Wong travels back to China with her husband and children to search for Yin and to apologize for her actions as a young student. Wong weaves the story of China in the first decade of the 21st century with her journey to undo past wrongs. The book is also a sequel of sorts to Wong’s earlier memoir Red China Blues: My Long March from Mao to Now, which details Wong’s time as a student at Peking University (including a brief description of her first encounter with Yin Luoyi) through her experiences as a journalist covering the Tiananmen protests and their aftermath.

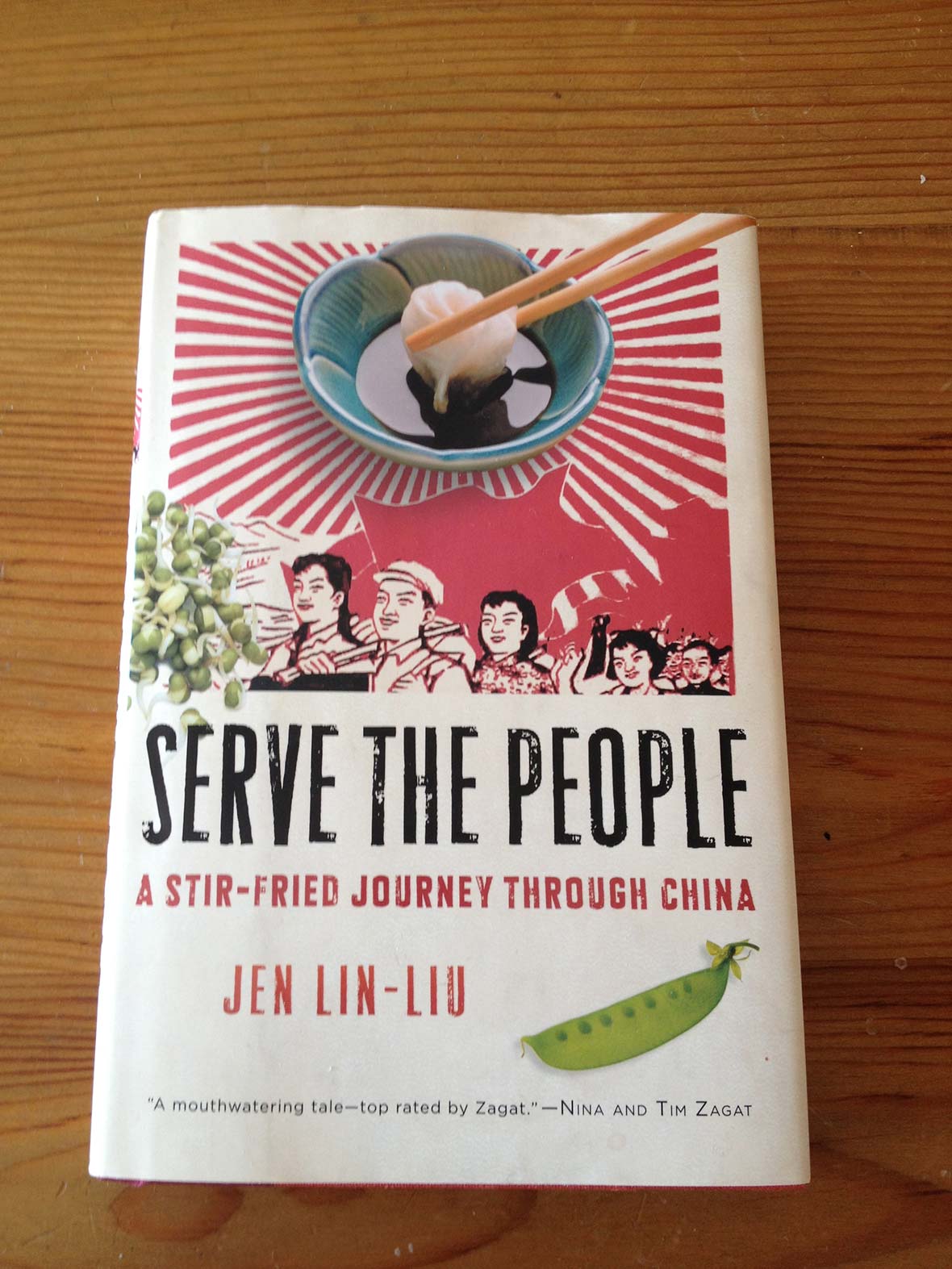

Serve the People: A Stir-Fried Journey through China

Jen Lin-Liu, Ivy League graduate and the daughter of Taiwanese immigrants to the United States, moved to Beijing in 2000 to explore the incredible world of Chinese cuisine. Her journey to explore both China’s culinary world and her own roots led her to enroll in the Hualian Cooking School. Lin-Liu then became a “noodle intern” at a shop in Beijing, an apprentice chef at a dumpling restaurant, and then worked in the kitchen of an upscale restaurant in Shanghai. Her experiences are interspersed with recipes for some of the dishes featured in the book. Along the way, Lin-Liu meets and befriends her fellow students, teachers, bosses, and co-workers. It’s a cross-section of modern Chinese society.

There are young economic migrants from other parts of China seeking a better life in the booming cities. Entrepreneurs trying to make it big (or at least earn a living) in the restaurant business. Urban elite diners seeking new levels of service and luxury. Given the importance of food in Chinese culture, Lin-Liu’s culinary adventures give her a front-row seat to the monumental economic and social changes happening in China in the 21st century. She is also the founder of Black Sesame Kitchen, which continues to offer special chef’s tables and small-group cooking classes at their courtyard culinary studio in the heart of Beijing.

The Last Days of Old Beijing: Life in the Vanishing Backstreets of a City Transformed

ABOVE: Michael Meyer’s discussing The Last Days of Old Beijing.

Beijing’s hutongs (the word translates as “alleyway” or “lane”) are the warp and weft of the city. Criss-crossing the historic center of Beijing, the hutongs have long been where most of the city’s residents lived and today remain an essential part of the city’s DNA. Nevertheless, the historic hutong neighborhoods of Beijing have long been threatened by economic development, urban renewal, and gentrification. In the years preceding the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, author Michael Meyer moved into an old courtyard home in a hutong just south of Tiananmen Square.

There he enlisted as a volunteer English teacher at the local school and became a part of the community even as the neighborhood was changing. “The Hand” (the term Meyer uses to describe the impersonal bureaucratic forces behind Beijing’s transformation) was an ever-present entity seeking out old structures for demolition. Meyer’s book argues that when neighborhoods are demolished, more than structures are lost. There are also the decades-old communities atomized in a rush for modernity. For example, in Meyer’s courtyard lived “The Widow,” an eighty-year resident of the neighborhood who can’t imagine a life lived in an apartment encased by glass and steel many stories above the ground. Like fellow author Peter Hessler, Meyer first came to China as a Peace Corps volunteer in the 1990s and Last Days of Old Beijing can be read as a Beijing counterpart to Rivertown, Hessler’s celebrated account of his time as an English teacher in a small city in Sichuan Province.

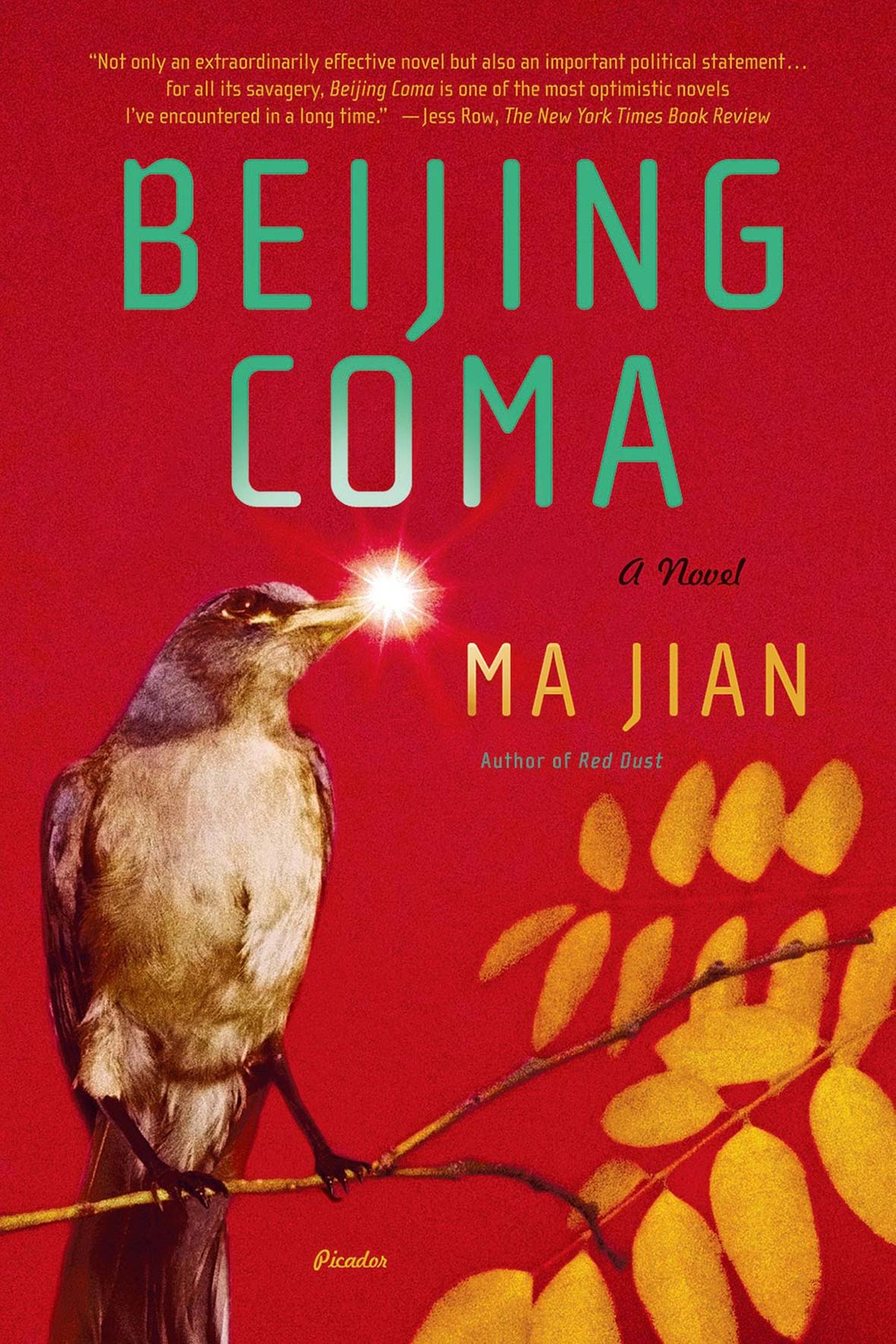

Beijing Coma: A Novel

Dai Wei was shot in Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989. His body paralyzed – but not his mind – from his sickbed Dai Wei relives his life from childhood during the Cultural Revolution through his university days to the events leading up to the June 4th demonstrations and his injury. Much of the book by Ma Jian (translated by Flora Drew) focuses on the heady, idealistic, and ultimately tragic events of 1989, a subject which goes unrecognized – if not actively suppressed – in Beijing today. Yet the events of that spring cast a long shadow over China even 30 years later. Trapped in his withering body, Dai Wei witnesses China in the post-Tiananmen era.

New technologies and ideologies emerge, the country rushes to forget the past and embrace a future where Olympic fever and runaway materialism replace political idealism. The novel is catharsis for its author Ma Jian, a participant in the Tiananmen protests who wrote the book in exile. The book is banned in China and visitors to the country are advised not to bring a hard copy in their luggage although e-reader versions should be fine. Also recommended is The People’s Republic of Amnesia, by former National Public Radio China correspondent Louisa Lim, which chronicles the efforts of the Chinese Communist Party to erase the events of 1989 from the history.

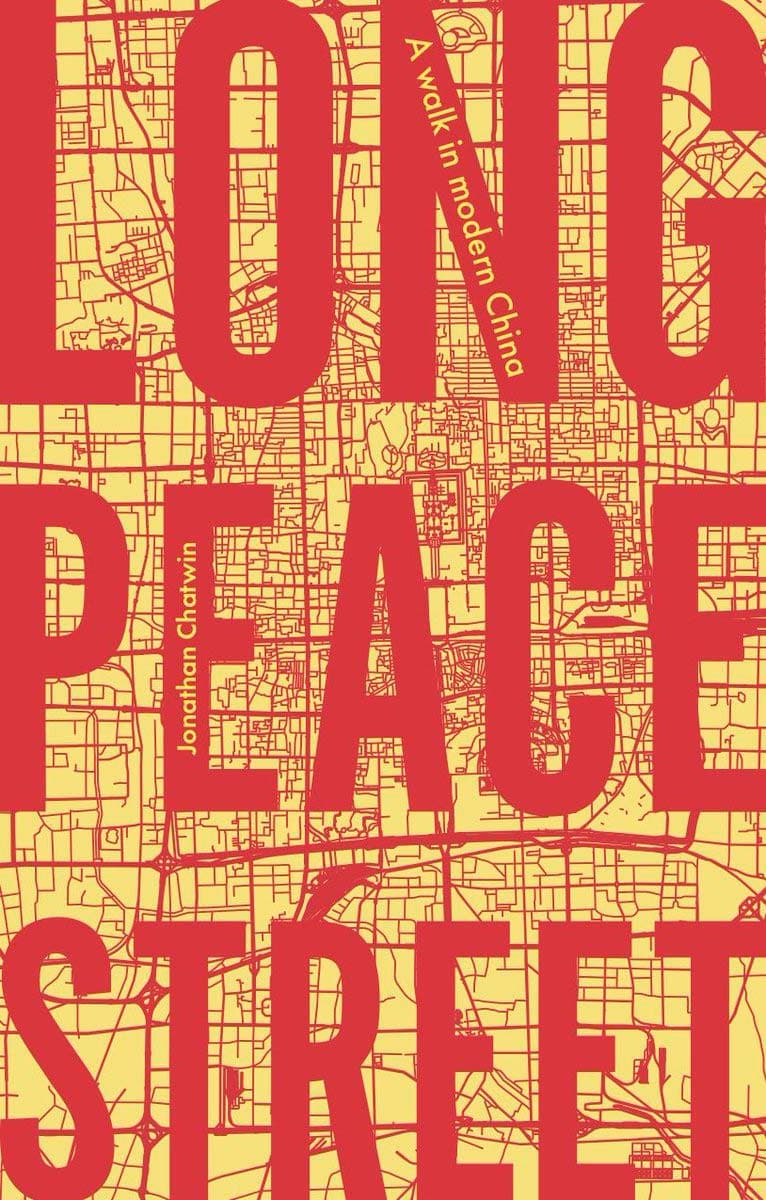

Long Peace Street: A Walk in Modern China

There are many lines which define Beijing. Famously, there is the Central Axis which runs south to north through the heart of Beijing’s best-known landmarks including Tiananmen Square, the Forbidden City, and the Drum and Bell Towers. There is also a line of more recent vintage, an east-west counterpoint to the old imperial south-north axis, which follows Chang’an Boulevard from the base of Beijing’s Western Hills past the grey monolithic offices of China’s ministries, intersecting with the Central Axis at Tiananmen Square and then running eastward toward Beijing’s Central Business District. Travel writer Jonathan Chatwin walked this line in the summer of 2016 and the book of his journey, Long Peace Street: A Walk in Modern China, is both a micro-travelogue and an extended meditation on modern China. From revolutionary cemeteries to the glittering skyscrapers where the country’s new elite live and work, Chatwin walks Chang’an Boulevard (the book’s title derived from an English translation of the street’s name) with each chapter focusing on a different part of the city.

Visitors to Beijing will enjoy Chatwin’s wry commentaries on some of the more famous sites, including the Forbidden City, while perhaps also being inspired to try and find some of the hidden gems which Chatwin discovers during his walk. Long Peace Street: A Walk in Modern China will be published in September 2019. In the meantime – or for those who love a good walk — also recommended is Alone on the Great Wall by British author William Lindesay which describes the author’s epic 1500-mile journey by foot along the length of the Great Wall of China.

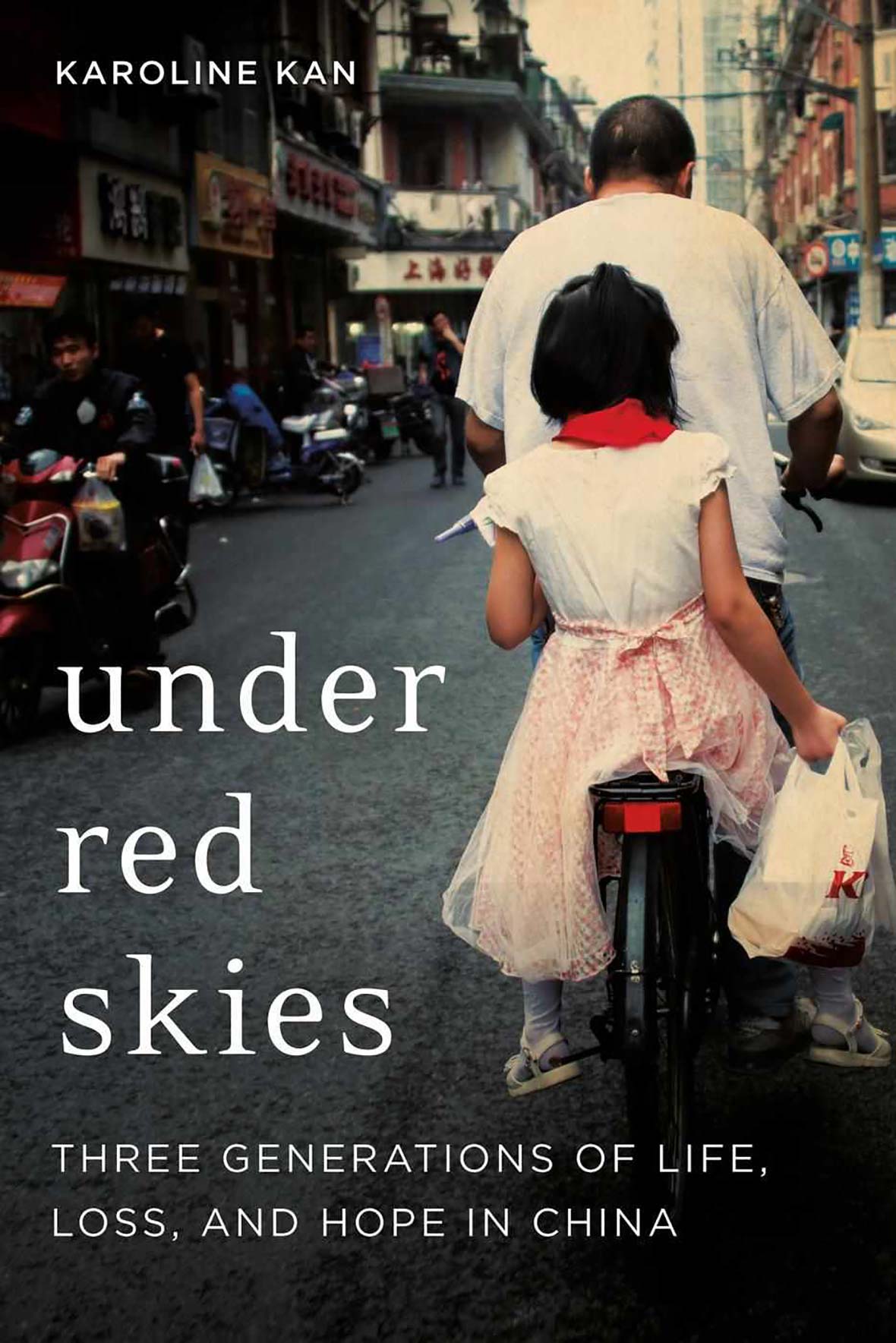

Under Red Skies: Three Generations of Life, Loss, and Hope in China

ABOVE: Cover of Under Red Skies: Three Generations of Life, Loss, and Hope in China by Karoline Kan.

In a stunning first book, Karoline Kan weaves her story with that of China’s millennial generation. Born in 1989 as her family’s (illegal) second child, Kan recounts her life growing up in rural China to her days at university and her experience working as an aspiring journalist in Beijing. There are stories of growing up, of first love, and of trying to reconcile the author’s own life and expectations with those of her parents and family.

Kan’s book is a glimpse at the incredible changes which have taken place in China in her lifetime and how the speed of development creates new opportunities for young people even as they struggle to find acceptance from parents who have trouble keeping pace with the seismic shifts in China’s society and culture. There is a scarcity of voices from Chinese women of Kan’s generation writing in English, and Under Red Skies is a look at the coming of age for a generation which will shape the future of China in the 21st century. Another recent book focusing on this generation is Wish Lanterns: Young Lives in New China in which China-based writer Alec Ash describes the challenges, hopes, and ambitions of six Chinese millennials.

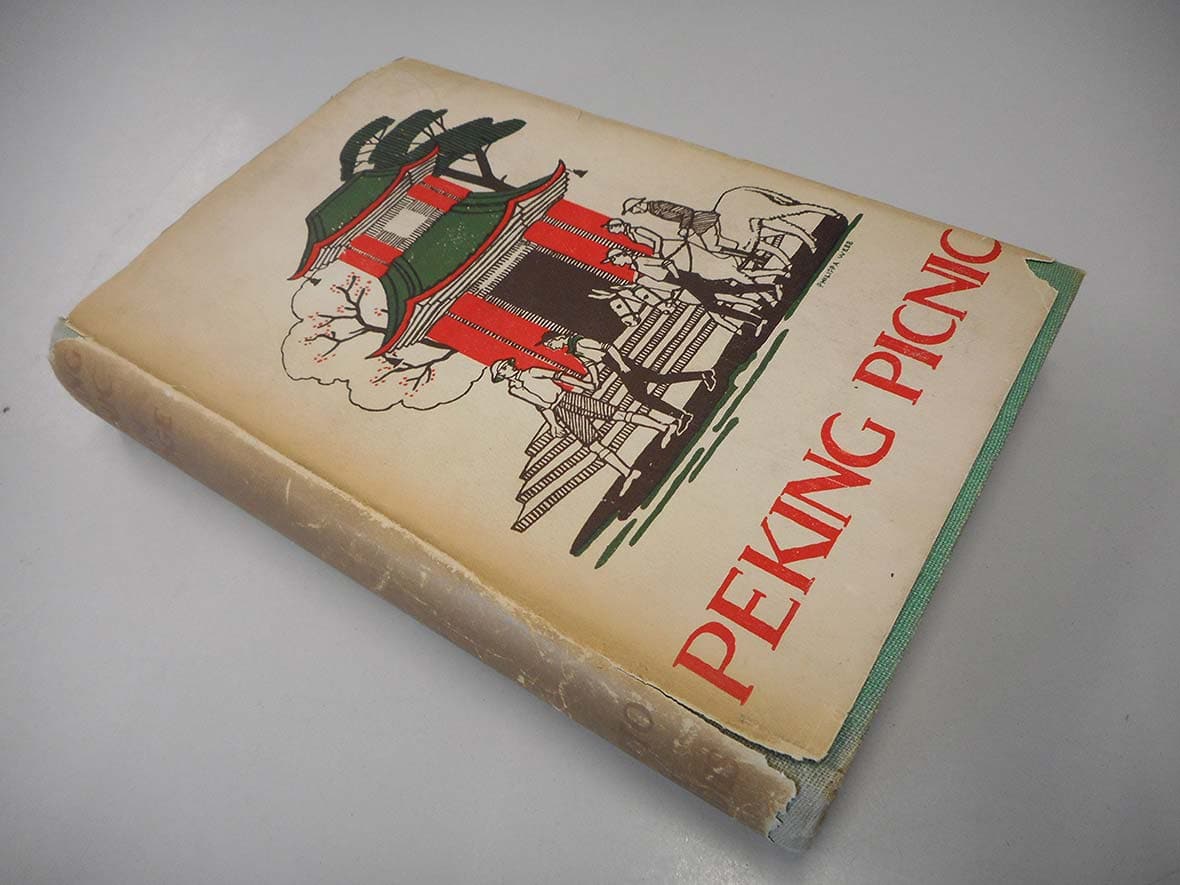

Peking Picnic

Laura Leroy is 37 years old and married to a British diplomat posted to China in the 1930s. The world of the Legation Quarter, the walled neighborhood where most of the city’s international residents lived, was a cloistered and sometimes claustrophobic environment. Unlike the sprawling international settlements of Shanghai, the Legation was an island of Western imperial privilege in a Chinese city that had remained in many ways unchanged since the fall of the last dynasty in 1912. Laura misses her home (and her children who are in school back in England) but has made the best of her time in China, learning Chinese and exploring the city and the surrounding countryside. She also finds time to have a series of affairs. Her relationship with her husband – who barely appears in the book – is distant. For amusement, she and her friends embark on a three-day trip to a temple in the hills outside of the city walls. The trip turns eventful, and what begins as a book best described as “Downton Abbey in China” transitions into something closer to Raiders of the Lost Ark.

The book is also particularly rich in its gossipy description of the foreign community in Peking at the time, and the author was certainly in a position to be privy to the secrets of the Legation Quarter. Ann Bridge was a pseudonym of Mary Ann “Cottie” Dolling Sanders, also known as Lady O’Malley, the wife of British diplomat Sir Owen St Clair O’Malley who served as British Consul in Peking beginning in 1925.

For a different take on the same era, there is also Harold Acton’s satirical (and hard to find) novel Peonies and Ponies. Acton was one of a group of expatriates who chose to eschew the comforts and confines of the Legation Quarter to live as gentlemen of art and culture in the Chinese neighborhoods of the city. Fellow “Peking Aesthetes,” as the group later came to be known, included the American writer George Kates (who wrote the memoir The Years that were Fat, Peking 1933-1940) and British scholar John Blofeld, who wrote the (only slightly) salacious memoir City of Lingering Splendor: A Frank Account of Old Peking’s Exotic Pleasures.