“The best way to learn about the food and heritage of Binondo is to eat!” exclaims Ivan Henares as we meet outside of a centuries-old church in the heart of Manila’s Chinatown. “This is the world’s oldest Chinatown,” he adds. “And I hope you haven’t eaten already, because we have a lot to try today.”

Ivan, a Manila native with Filipino-Chinese ancestry has been leading food walks around the city’s Binondo district for years. He knows where to find the juiciest dumplings, the freshest Lumpiah, and the best home-style cooking. Ivan’s expertise was even recruited by the late Anthony Bourdain when he guided the chef around the city in an episode of Parts Unknown.

Today, my appetite for both food and history would be in safe hands. With Ivan, I would eat well, and I would be thrown into the heritage of Binondo.

Binondo: The Oldest Chinatown in the World

ABOVE: Binondo lumpia.

Ivan leads me under swaying red lanterns towards a small shop front on a chaotic street close to Binondo Church. Our first stop would be endless servings of Lumpia, the Filipino version of Chinese spring rolls.

As we sit down, Ivan explains how the Binondo district was formed in 1596 by the Spanish colonial rulers, who a few years earlier had made Manila the capital of what would become the Spanish-Philippines. Manila already had a long history of trade with the Chinese, and the region had connections with China long before the Spanish arrived

Binondo is located across the river from Intramuros, the walled city built by the Spanish to control their new colony. “The Spanish named this area Extramuros because it’s outside of the walls,” Ivan says. “The idea was to keep mass Chinese immigration away from the main city, and anyone who converted to Catholicism was allowed to live in Binondo.”

ABOVE:Chinese-Filipino restaurant.

“The outer city of Manila is a city that’s built on immigration,” Ivan says as the Lumpia arrive at the table. “This is one of the oldest districts in the city, and because the Spanish didn’t want the Chinese influencing them in their own part of Manila, that’s why we can find the best spring rolls here!”

The Lumpia are vegetarian, and they are fresh, not fried. “The spring rolls here are more like a wrap”, Ivan says happily as we dig into the first plate, before ordering a second. “They are distinctly local now, but in many ways similar to the spring rolls you still find in Hokkien, in China.”

The Melting Pot

Hokkien culture and language originated in an area of China now known as Fujian. “Ninety percent of Chinese immigration to Manila was from Fujian,” Ivan says. “The famous Binondo Church though is very un-Chinese of course. To survive in the Spanish days, you needed to convert to Catholicism. The Spanish wanted spices and gold, but they also wanted souls!”

Over the last few centuries, Binondo, like other Chinatowns around the world, has become a melting pot of languages, religions and cultures. “Over time, a unique culture has formed, and in the Philippines, descendants of Chinese immigrants are called Chinoy – like a Chinese-Pinoy!”

Chinese immigrants brought noodles with them to Manila, and now one of the most popular dishes in the country is Pancit Canton or Cantonese Noodles. In fact, Ivan explains how the majority of Filipino-Chinese dishes are based on Cantonese dishes, despite Cantonese immigrants making up only a small proportion of the immigrant population.

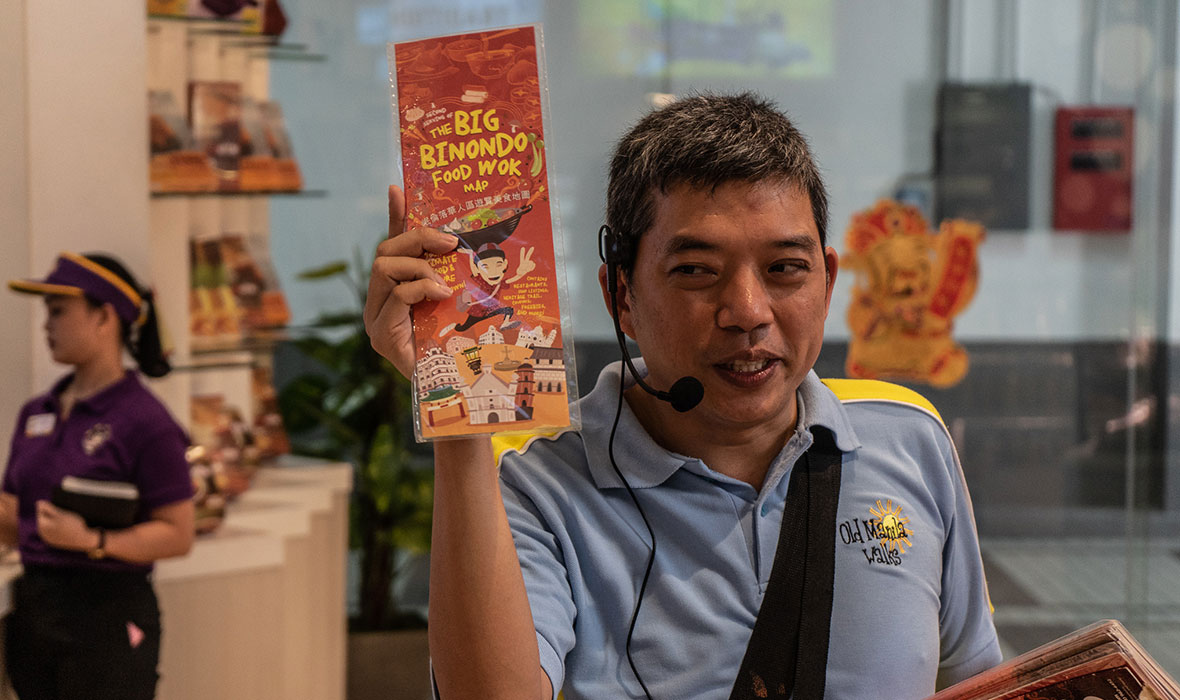

ABOVE: Ivan holding a food map of Binondo.

“The Hokkien were traditionally traders, not cooks,” explains Ivan. “The Cantonese had a reputation for being very good cooks. So much of the influence on the food is from Canton.”

At the next restaurant – a small family-run business that seems to have more hungry clientele than it does tables – Ivan introduces me to classic home-cooked style Chinoy cooking, including the pancit canton I’ve been waiting to dig into.

“This is the food my Grandma would make,” Ivan happily tells me as a feast is served, and I hungrily try noodle dishes, oyster omelette, spicy meats rolls served in tofu skin, bean sprouts in vinegar sauce and more.

Dong Bei Dumplings

ABOVE: Sun washed sign to Dongbei Dumplings.

Despite bursting from plate after plate of food, Ivan still had one more restaurant to show me in Binondo. To round off our culinary journey through the world’s oldest Chinatown, the final stop would be Dong Bei Dumplings.

“Our next stop is small,” Ivan warns. “It has zero ambiance. But, as my Dad said, you don’t eat ambiance.”

Dumplings are incredibly popular in the Philippines, and in any supermarket or fast food store, you can buy Siomai the classic Filipino take on a classic dish.

“We aren’t having those though, because you can have them in any 7/11 store in Manila,” says Ivan. “These dumplings are very different and are from a part of China which historically the Philippines had no immigration from until about 10 years ago.”

At Dong Bei Dumplings, diners are crammed into a small shop front while a team of cooks rapidly roll out dumpling after dumpling at the entrance.

“These dumplings originated in the northern part of China, close to Vladivostok!” Ivan exclaims as huge, steaming bowls of dumplings are served up.

I dip the beef and chive stuffed dumplings into chili sauce as I precariously use chopsticks I’m handed.

“These northern style dumplings are quite new here,” Ivan tells me as I slurp down dumpling after dumpling. “But as you can see, the food scene in Manila is still constantly evolving!”