For the first time in my life – I had become a gentleman.

Novelist, composer, and prestigious polymath extraordinaire Anthony Burgess set sail from Southampton bound to Singapore aboard the Dutch Passenger liner Willem Ruys on the 5th August 1954. His wife Lynn enjoyed endless gin and tonics on deck while the Siamese family cat, Lalage, established her sea legs chasing the odd stow-away rodent below deck. Burgess, ever the linguist, set about expanding his Malay vocabulary, and in the evenings, the budding wordsmith aged 37, the son of a Moss Side tobacconist, and an all-round literary ragamuffin, dressed for dinner.

“For the first time in my life – I had become a gentleman.” This adventure was a true turn of fortune. A twist of fate of Dickensian misfortune sentenced the two-year-old Burgess to a life of near orphanage. Losing both his mother and sister to the Spanish influenza raging through Europe and killing 20 million, the author was adrift most of his life.

Burgess grew up in the Golden Eagle pub where his wayward father drank and played piano while his illiterate step-mother tended the bar with a soiled beer towel wrapped around her shoulder. Somehow Burgess made it through Manchester University graduating with a degree in English literature, a document that surprisingly became his passport to the Far East.

Grammar Teacher Goes to Singapore

ABOVE: Malay College in Malaysia’s Kuala Kangsar – at which Anthony Burgess was a school master.

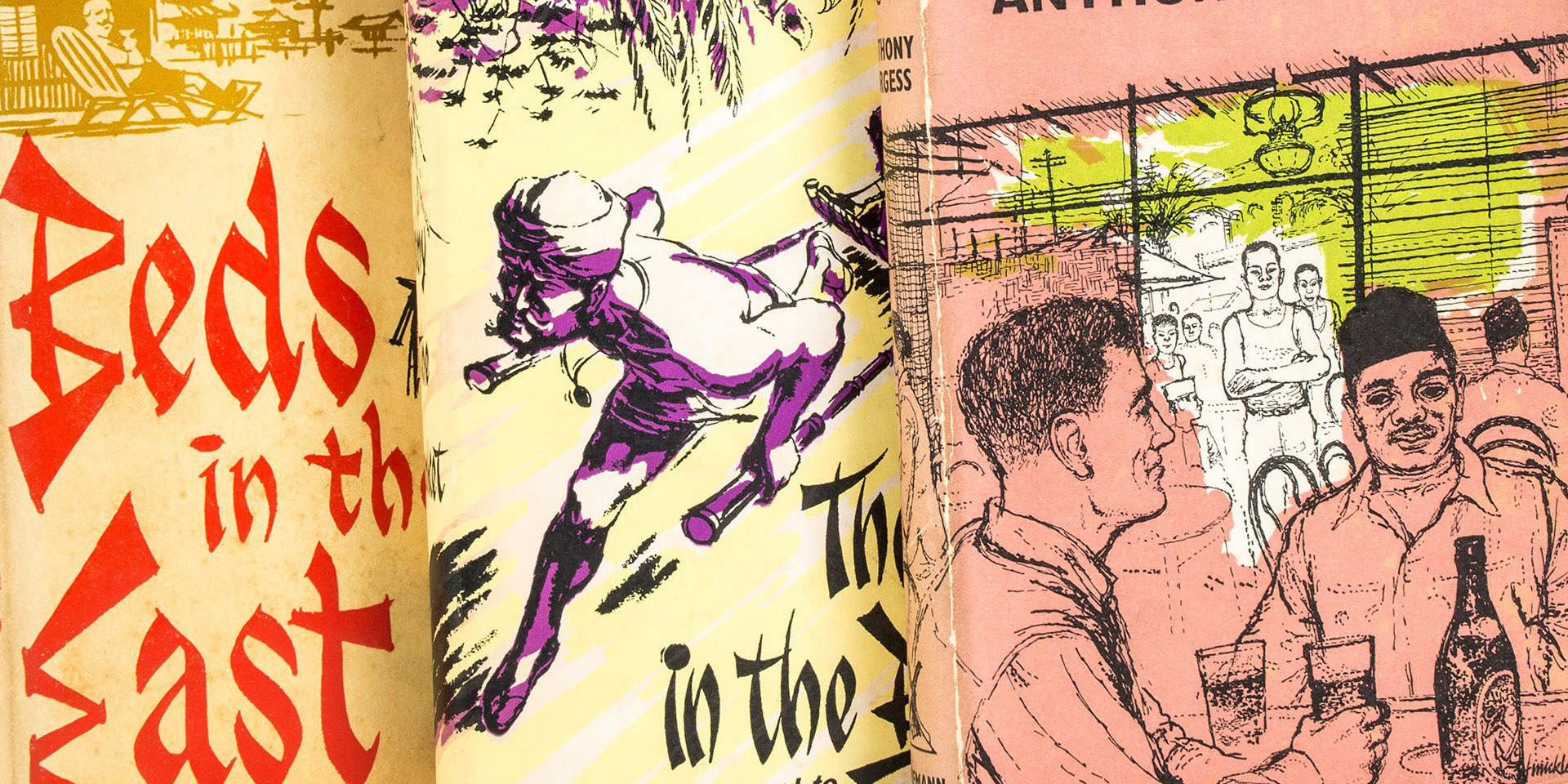

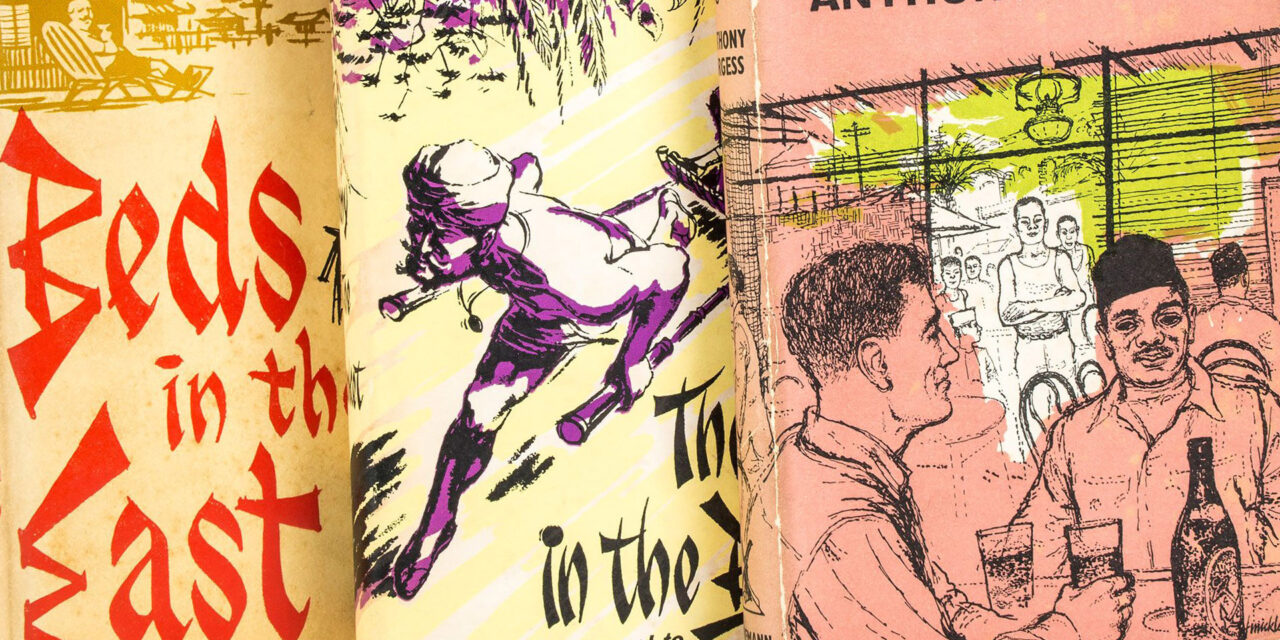

Over a decade before Burgess was to pen the ultra-violent Clockwork Orange, he eked out a living as a school teacher at Banbury Grammar in Oxfordshire. Burgess had drunkenly written an application to work overseas. With no clear memory of ever applying for the British Colonial Services, Burgess was called to London for the resulting job interview. After passing the interview Burgess discovered the position was for a school in Malaya. Burgess, sensing a wave of serendipity, accepted the offer as a School Master at the Eton of the East Malay College, Kuala Kangsar. Here he became a writer of true standing with his semi-autobiographical trilogy Time for a Tiger, The Enemy in the Blanket, and Beds of the East.

Unlike many other wordsmiths who visited Southeast Asia, Burgess really got to know the local people, learned their language, and ate their food. “I wanted to be accepted as a Malayan,” Burgess wrote, “I proposed entering Islam, which would have entitled me to four wives but barred me from eating ham for breakfast. My name was chosen for me – Yahya bin Abdullah – and I started to study the Koran.”

ABOVE: Achille Lauro, christened the Willem Ruys, which took the celebrated novelist Anthony Burgess to Singapore.

The Dutch liner cruised across the Mediterranean, threaded down through the Suez Canal, and headed across the Indian Ocean before arriving at the port town of Singapore. Now a tiger-economy built on tech-start-ups and venture capitalists; a landscape where high finance skyscrapers loom over a sports arena, a casino, and luxury hotels. Singapore in the 1950s was a city of street gangs, illegal trade, and shady back alleys. Shirtless street children ran amok the kampungs, the Singapore miniature zoo was 50 cents, and the cinema cost a nickel. Men squatted upon chairs in coffee shops occasionally spitting chewing tobacco into aqua-blue porcelain spittoons. Gangs betted on spider fights as illustrated in Ming Cher’s wonderful novel Spider Boys. Now much of the spirit of the 1950s remains around town, at least visually, with old shop-houses converted into bars and coffeehouse with names like Flying Monkey and Bitters & Love.

Once Burgess arrived, his wife promptly collapsed from nervous exhaustion. Burgess calmly put her to bed before venturing out to explore the city’s nefarious nightlife alone.

Night Train to Home in Kuala Kangsar

ABOVE: Sunset at Victoria Bridge in Kuala Kangsar, how Anthony Burgess came to find his strange home in Malaysia.

From Singapore the Burgess family took the night train to Kuala Kangsar in the northwest of Malaysia and not far from the border with Thailand. As the train lurched forward his pen arm (quite distinct form his drinking arm) found a life of its languid own.

“The river Lanchap gives her state its name. It has its source in the deep jungle, where it is a watering place for a hundred or so people who share it with tigers, hamadryads, bootlace-snakes, leeches, pelandoks and the rest of the bewildering fauna of up-stream Malaysia.”

When the train would changed line at Ipoh and continue north toward Siam (now Thailand), Burgess continued his thoughts and sketches plucking place-names and ideas from his fertile imagination like exotic flowers.

“As the Sungai Lanchap winds on, it encounters outposts of a more complex culture. Malay villages where the Koran is known, where the prophets jostle with nymphs and tree-gods in a pantheon of unimaginable variety. Here is a little work in the paddy-fields suffices to maintain a heliotropic, pullulating subsistence. There are fish in the river, guarded, however, by crocodile-gods of fearful malignity.”

The Malay College Kuala Kangsar, established in 1905, educated the Malaysian elite, and Burgess, his wife, and the family cat arrived slightly disheveled from the journey and settled in best they could to colonial life.

Life in the Pavilion

ABOVE: Aerial view of Ubudiah Mosque located in Kuala Kangsar in Perak.

The town was home to the sultans of Perak and center of rubber and tin-mining operations. The Burgess’s were housed in the King’s Pavilion along with a gaggle of the dormitory students. Commandeered by the Japanese military during the Second World War the Pavilion had bloodstains on the bathroom floor as a reminder of its torturous past.

The building still stands in Kuala Kangsar haunted by the wounded spirits of former brutal persecutions. Burgess and Lynn lived in a flat on the top level of the building.

Burgess after a breakfast of tea and bananas walked to the college each weekday morning. His wife skulked mainly in the apartment where she complained about the noisy students and boisterous ghosts while marinating herself in gin. Burgess, the House Master, out on his daily walk to and fro school passed the town’s market, writing in Time for a Tiger.

“Old women crouched over bags of Siamese rice, skeps of red and green peppers, purple eggplants, bristly rambutans, pineapples, durians. Flies buzzed over fish and among the meat bones, ravaged, that lay for the cats to gnaw. Here and there an old man slept on his stall with, for bedfellows, skinny dressed chickens or dried fish-strips.”

Returning back to the Pavilion Burgess frequented local bars (much to the shame of the other teachers and staff who wouldn’t dare be seen dead outside of the European clubs) and sketched his novels while drinking Tiger beer.

He became so fond of the brew that he named his first Malaysian novel – Time for a Tiger – after the beer’s advertising slogan.

ABOVE: A typical red, British phone box still standing today in Kuala Kangsar, a remnant of the colonial age.

References:

Andrew Biswell (2005) Picador. The Real Life of Anthony Burgess.

Anthony Burgess (1956) Minerva. Time for a Tiger.

Anthony Burgess (1958) Minerva. The Enemy in the Blanket.

Anthony Burgess (1959) Minerva. Beds in the East.

Anthony Burgess (1987) Grove Press. Little Wilson and Big God.

Anthony Burgess (1990) Penguin. You’ve Had Your Time.

Geoffrey Grigson (2013) YouTube, various.

The Burgess Variations. (1999) BBC.

“I arrived in Malaysia a teacher and left as a writer,” he fondly recalls in the television documentary The Burgess Variations. Burgess revisits the town, teaches a class at the school and speaks Malay with some locals in a cafe.

Had he isolated himself from the indigenous folk, as many writers of the time did, his work would have taken a different direction. Like Shakespeare before him, Anthony Burgess got his hands dirty with the working classes. “Why this urge to record Malaya in fiction?” Burgess asks himself onscreen while sat at a Malay bar in the documentary. “Surely it had been done before and very adequately by William Somerset Maugham,” he continued. “True enough, but it was very much an outsider’s Malaya. The planters and their wives, bridge in the club and adultery in the District Officer’s bungalow. The Chinese and the Indians were very shadowy figures, and the Malays were reduced to an obsequious pair of brown feet on the veranda… at least I got to know the people, in fact I got to know the Malays rather better than Joseph Conrad. I taught their sons, I spoke their language.”

Indeed he did and his work in the Malayan trilogy is still here for whenever we wish to transport ourselves back in time to 1950s Malaysia.