The Aqua Mekong is unique in Southeast Asia. Perhaps no other vessel in the world – save the company’s namesake on the Amazon, the Aria Amazon – capably shoves a boutique five-star hotel into a vessel that is equal parts explorer and ultra-luxe. Travelogues sailed in her for a high-water journey across Cambodia for wildlife, history, and five-star dining in august company all the way to Phnom Penh.

After breakfast at the Bill-Bensley designed Park Hyatt Siem Reap, cruisers take a shuttle to the Chong Khneas pier amongst the throng of day trippers and tourists packed onto junkers. Aqua Mekong travelers board, however, a comfortable skiff to what will be their home for the next four days to a week.

ABOVE: Exterior of the Aqua Mekong at sunset.

To see the Aqua Mekong hove into view is quite a treat. After passing several dozen barking clunkers banging away on the lake, the Aqua Mekong is a shining, glass, three-storey palace floating on the calm waters of the Tonle Sap. With as much focus on sustainability as feasible – as it pertains to both emissions and waste management – the Aqua Mekong is a modern, intelligently-designed luxury experience upon which the word “cruise” is anathema. It is an expedition.

ABOVE: Images of the Aqua Mekong.

While the ship is capable of handling 40 guests, this lucky journey barely broke double digits, leaving the expansive decks and lounges open and quiet. But even at the height of occupancy, the staff to guest ratio is 1/1. This is evident as guests step off the relative excitement of the skiff into the objectively luxurious interior of the Aqua Mekong, greeted by staff, a cold towel, and a welcome drink on the top deck.

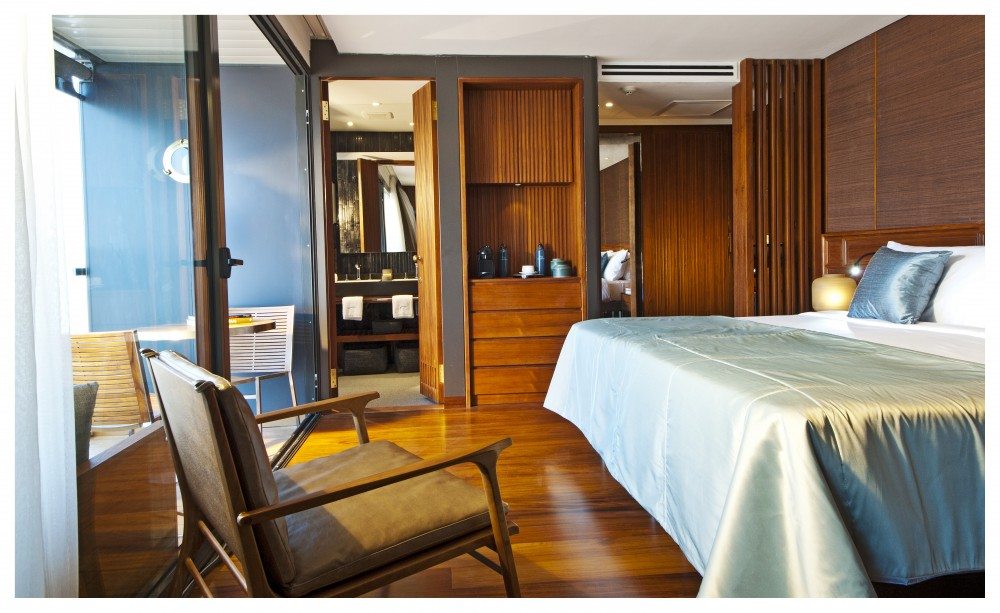

ABOVE: Images from the Aqua Mekong quarters.

As it pertains to quarters, both fist and second deck rooms feature balconies, while other other rooms are fitted with windows that open to the lake; travelers are reminded to keep these closed in the darker hours as the bugs that provide the food for many birds are no respecters of boarding passes. The quarters are made up thrice a day, and travelers have nary an appointment to keep but their adventures in the wilds of Tonle Sap.

In any event, the rooms are spacious well appointed, far from the “cruise” staples of a power toilet and hard bed with starched sheets. No, in these, the traveler might as easily imagine themselves in a cozy urban hotel in somewhere like Shanghai, but rather than the Bund the view is a cultural playground of Southeast Asia’s largest lake moving by at 12 knots.

For guests numbering more than two – or for those who just wish to splash out on a larger space – there are adjoining rooms that allow travelers two rooms and two bathrooms, as well as a sitting area on the balcony.

Besides the plush rooms, there is plenty to keep the active traveler distracted, from a stocked library with a fashionable see-through foosball table to a private screening room decked out in leather chairs and films pertaining to Cambodia and Vietnam. A fully stocked bar on the third deck is always manned, and the cocktail and liquor list is world-class.

The outdoor areas are very un-cruise-like: classy, quiet, well-staffed, allowing shipmates to view the rainbow-colored skies and orange waters of Tonle Sap in peace. Many are driven indoors by the insects at night, but, blessed as this traveler is with an immunity mosquitoes, hours were spent staring at an impossibly starry sky, with light pollution little more than a theory on a state-sized lake in undeveloped Cambodia.

Natural World

ABOVE: Cambodian flag flies over an outpost where travelers can view the nesting birds of Tonle Sap from afar.

This guy here? He used to kill the birds. Now he helps them.

The first excursion takes travelers into Cambodia’s wetlands and introduces them to the fragile natural environment of Tonle Sap in the form of the Prek Toal Bird Sanctuary. Guests wake uncommonly early for a shot to see nesting pelicans, cranes, and all manner of feathery friend on the winding, hyacinth-clogged waterways of Prek Toal. No other expedition besides the Aqua Mekong, so our guide claims, is permitted in these protected waterways.

Our small group of travelers – decked out in flip-flops, binoculars, and a complementary metal water bottle – travel into the wetlands to find our guides floating in a longtail boat, moored to a dying tree and dressed from hat to foot in camouflage: forest rangers.

“These guys help the birds,” says Smiley, our guide on this journey. They hop onto our boat as Smiley tells us they would get lost in the winding and constantly shifting waterways without their help. “This guy here? He used to kill the birds. Now he helps them,” Smiley says, pointing to the younger and thinner of the pair who changed trades from poacher to ranger.

ABOVE: Wetlands of Tonle Sap.

We are guided through the wetlands to a semi-permanent outpost built high in the trees with sticks, and rope. About half of our group were brave enough to visit the summit. From the perch, travelers can stare through a telescope at the nesting pelicans and storks, birds so numerous that even from more than a kilometer away they turn the green wetlands white with feathers.

ABOVE: Images from the wetlands of Prek Toal.

Despite destructive dam projects in China, Thailand, Vietnam, and Laos, this isolated region of Cambodia maintains an impressively diverse ecology. The birds feed on the dwindling number of fish that populate these waters, including the giant snakehead and the famed Mekong giant catfish. There are even a small number of wild alligators here; though small, travelers are taken briefly to see where the gators are farmed for food. It’s not just the birds that come here for the fish. It is the bounty of these brown waters that also brought the people to Tonle Sap.

The Water Villages

ABOVE: A girl in Moat Khla pulls a boat forward on the shallow waters of Tonle Sap; more than a million people make their home on this lake, most of them Vietnamese.

The most popular excursions for travelers on the Aqua Mekong are undoubtedly those into the water villages that dot the ever-moving edges of Southeast Asia’s largest lake. Travelers on their first visit to the region will be surprised by the very Vietnamese feel of the culture in the area. Around 1.2 million people make their livelihoods on the edges of Tonle Sap, and most of those who do are ethnic Vietnamese.

It may look like Cambodia, but for many this is the land of the stateless: undocumented, underprivileged, and unrecognized. A remnant of the long, complex history of Hun Sen and the Vietnamese, the government often attempts to remedy this to little effect. For now, they simply float. Our Vietnamese guide, Thach Chariya, explains in detail.

The floating villages are a marvel of human ingenuity. Even in poverty, there are floating Circle K stores, floating fire stations, and floating schools. The children are photogenic, at work, at play, and at home. When the waters rise, many of these homes and the families in them float away on the barrels that hold them aloft, but never for long.

ABOVE: Children play after school at a water village in Tonle Sap.

The many Aqua Mekong excursions through the water villages of Tonle Sap provide a wealth of cultural experiences. Travelers get the chance to meet and pray with Buddhist monks and novices. Visitors kayak through the waterways, or less adventurous souls (my unboyant self included) may stay in the skiff and wander about buying tarantulas and bugs to eat later in the day with plush, complex cocktails as the sun sets.

ABOVE: Girls play outside of a floating market on Tonle Sap.

The floodplain of Tonle Sap goes on for miles, and the people there turn as much to agriculture, specifically rice, as they do to the waters for sustenance. One such man was Mr. E, a resident of Andong Russei who at 68 can still shimmy up through the branches of the region’s palm trees; he makes his living with his very, very strong rice wine.

ABOVE: People in and around Tonle Sap water villages.

The smiling and almost impossibly happy Mr. E, taking a look at my size, offers a second shot of his rice wine before climbing a palm tree. He says it was his sixth of the day. In a moment, Mr. E is up the tree and shouting the one word of English he seemed to speak, “Hello,” hanging onto the tree with one foot and one hand. Here too travelers meet with craftspeople and locals, including a woman who makes Cambodia potware by hand, without so much as a treadle. She walks slowly in circles around a log and beats it with her weathered hands.

Kampong Chhnang and Andong Russei are are some of the more photogenic spots on a nonstop photogenic trip. In the dry season, the fields of rice are golden, and palm trees – with an almost imperceptible ladder like structure attached – break through the soft sunlight. That soft sunlight comes courtesy of the constantly burning chaff that time of year, but it still makes for excellent photos. Travelers can cycle through these streets, and, as with any Aqua Mekong excursion, be met by the boat with a welcome drink and a cold cloth.

ABOVE: Scene from Andong Russei. The burning chaff makes for excellent photography, and ladders can be seen going up the palm trees.

For travelers who want to test their mettle against one of Cambodia’s more difficult temples, there are the 500 steps of Udong mountain. While the temple itself is not that old, notable for its shining white lacquer, the view of the surrounding area is worth every step; though, it should be noted that our guide took our party of not-so-fit adventurers a third of the way up the Udong mountain climb. Going down the 500 steps was much easier and travelers are greeted with shopping and an easy trip back to the skiff.

The Food

ABOVE: Eggplant dish from the Aqua Mekong.

I love to introduce our guests to Asian food – Vietnam food, Thai food, and Cambodian,

The constancy of the five-star cuisine is not something easily forgotten. Visit Moat Khla an pray with monks? Come back for dinner with all the bells and whistles of a world-class hotel on the land. Cycle through Andong Russei and throw rice wine down your gullet? Return for delicately prepared shrimp and fresh eggplant. The brains often touted behind the kitchen aboard the Aqua Mekong are those of executive Chef David Thompson, a giant in the field, and Chef Sophal was working the kitchen during our journey.

His third year aboard the Aqua Mekong, Phnom Penh native Chef Sophal cut his teeth in the cooking world at Raffles in Singapore, perhaps the most luxurious hotel in a city known for its opulence.

“After working at Raffles for about three years, then I moved onto Siem Reap,” says Sophal. “It’s different cooking from Raffles. Raffles has more variety of restaurants; here we have only one. It’s one dining room and one bar.”

ABOVE: Chef Sophal in the Aqua Mekong dining room.

A door is opened in the dining room, and I am able to see how the other half lives on the Mekong: white walls, pipes, tiny oval doorways, and metal floors. It’s quite a change from the wooden patios and chic design guests normally see. In the bowels of the ship are, strangely, the stomach. Here, the kitchen works out of sight, in a crisp, clean kitchen of stainless steel.

“I love to introduce our guests to Asian food – Vietnam food, Thai food, and Cambodian,” says Sophal. “Especially the curries and the num banh chok (noodles).” From the satay to the eggplant, Sophal’s passion for Asian cuisine shows.

Phnom Penh and the Journey’s End

ABOVE: Phnom Penh Palace spire.

By the time travelers reach Kampong Chhnang, the expansive, ocean-like Tonle Sap Lake gives way to the Tonle Sap River, one of the planet’s few that has its flow reversed when the Mekong floods the lake and its surrounding lands. From there on out, travelers can look from the floor-to-ceiling windows of their plush suites onto the colorful and quiet riverside. Sunsets that go on for miles are replaced by stilt-houses and long-tail boats. This isn’t a world of endless flood or of the stateless, this is the capital in small bites.

As Phnom Penh approaches, travelers are even able to see a few high rises here and there, and when the ship moors in Phnom Penh, guests who boarded for a four-day journey have one excursion left.

As travelers exit by tuk-tuk, they see, finally, the fabled Mekong. The brown silt of the wetlands, lake, and river of Tonle sap mix with the dark blue and black of the Mekong. The architecture all of a sudden seems strangely permanent; after days of houses on stilts and barrels, Phnom Penh seems very tangible.

It is in this sense of the palpable that travelers are taken to Phnom Penh palace; the yellow brick road, flocks of pigeons, and architecture make this a special place. However, while the history in the walls may speak volumes, the volume on the tourists could be turned down a tad. The schedule necessitates a an early arrival at Phnom Penh palace, but it’s hard to be early to one of the most popular sights in the capital. It may stand as a symbol of Cambodian history and sovereignty, but these days it’s more of a Chinese satellite state in the early hours of the afternoon.

ABOVE: The final excursion includes the grim but essential stop at S-21.

In the end, and very sadly, it is S-21 that puts travelers more in mind of the Cambodia they’ve heard spoken of in newspapers and history books. It is not the golden spires and Buddhist statues of a palace that so represents Cambodian history on this trip, but the broken walls and ammo-box toilets of a school cum torture chamber.

Much has been written about S-21. Indeed, authors sell their memoirs inside its walls. Many try to skip the audio guide to museums of this sort; this is a mistake at S-21. The guide is key. Tourists – some dressed well, some students, some in hot pants and sunglasses – follow the guide from stop to stop rapt in the story, listening to explanations, descriptions, and even interviews with former torturers at S-21. Travelers seem uninterested in looking at one another. In rooms filled with skulls and pictures of the dead, people stare ahead and alone when they cry. If S-21 is anything, it is a dark reminder of what we hope never again to be.

It is on this grim dark note that the enchanting journey of the Aqua Mekong comes to an end. After lunch on the Sora rooftop bar at the new Rosewood in Phnom Penh, many get back on the ship and head for the Killing Fields and then on to three more days to Saigon, but Travelogues’ journey was a distinctly Cambodian expedition.

The dark end to the journey is fitting for this lake. The troubles of Tonle Sap remain long after visitors disembark. The damming and the environmental problems of planet Earth are wreaking a slow apocalypse on the people of Tonle Sap. It is a world of incredible beauty treated with a willful disregard.

The Aqua Mekong is a once-in-a-lifetime luxury journey to be sure, but what’s special about the Tonle Sap section of the Aqua Mekong are the memories that beget lessons. From the birds of Prek Toal and the rice wine of Andong Russei to the floating villages and halls of S-21, travelers will remember their luxury expedition on the Aqua Mekong.