Deep inside Manila’s Intramuros citadel, a Filipino hero is suspended in mid-air as he collapses. Behind him, smoke billows from the rifles of a Spanish firing squad, which has just unloaded their ammunition. The infamous moment depicted by this painting is the 1896 execution of Dr Jose Rizal, perhaps the most revered individual in the modern history of the Philippines.

He was a celebrated artist, poet, mathematician, physician and leader of a bloody rebellion against the Spanish occupation of his home country. In death, Rizal’s influence persisted. He became a martyr who inspired the Philippines to regain its freedom after three centuries of Spanish rule.

No one may ever be more beloved in the Philippines than Rizal, whose name appears everywhere throughout the country, from monuments to roads, public buildings, and community spaces. Adjacent to Intramuros is Rizal Park, Manila’s most famous green space.

It was here Rizal was put to death. The exact location, a grassy knoll encircled by trees, is now marked by metallic sculptures which illustrate the same violent moment as the aforementioned painting. This artwork hangs inside one of the area’s key tourist attractions, the Shrine of Jose Rizal.

Part-memorial, part museum, this impressive facility is housed in a former military barracks where Rizal was imprisoned by the Spanish in 1896. His alleged crimes, according to a sign at the shrine, were “rebellion, sedition, and formation of illegal societies”. Incensed by his execution, the Philippines fought back, the museum explains. A revolution was launched and by 1898 the nation had regained independence.

This history is embodied by Intramuros, one of Asia’s finest citadels. Wedged between Rizal Park to its south and the Pasig River to its north, this 16th century wonder is Manila’s best tourist attraction, and will soon be even more appealing due to the addition of new bicycle lanes and public transport options.

In 1571, Manila was sent into panic by a sight along that same river. Sailing up its waters was a fleet of Spanish conquistadors, led by Miguel Lopez de Legazpi, who launched a violent rampage. A swathe of Manila, which then was a small Muslim community, was laid to waste and the European invaders set about building their own settlement.

Soon, the Spanish themselves were besieged. That ambush by Chinese pirates convinced them they needed to fortify their growing colony at Manila, so they built the commanding Intramuros. Spread across 146 acres, Intramuros is surrounded by lofty, 6m-thick walls, and lined with well-maintained Spanish-era buildings.

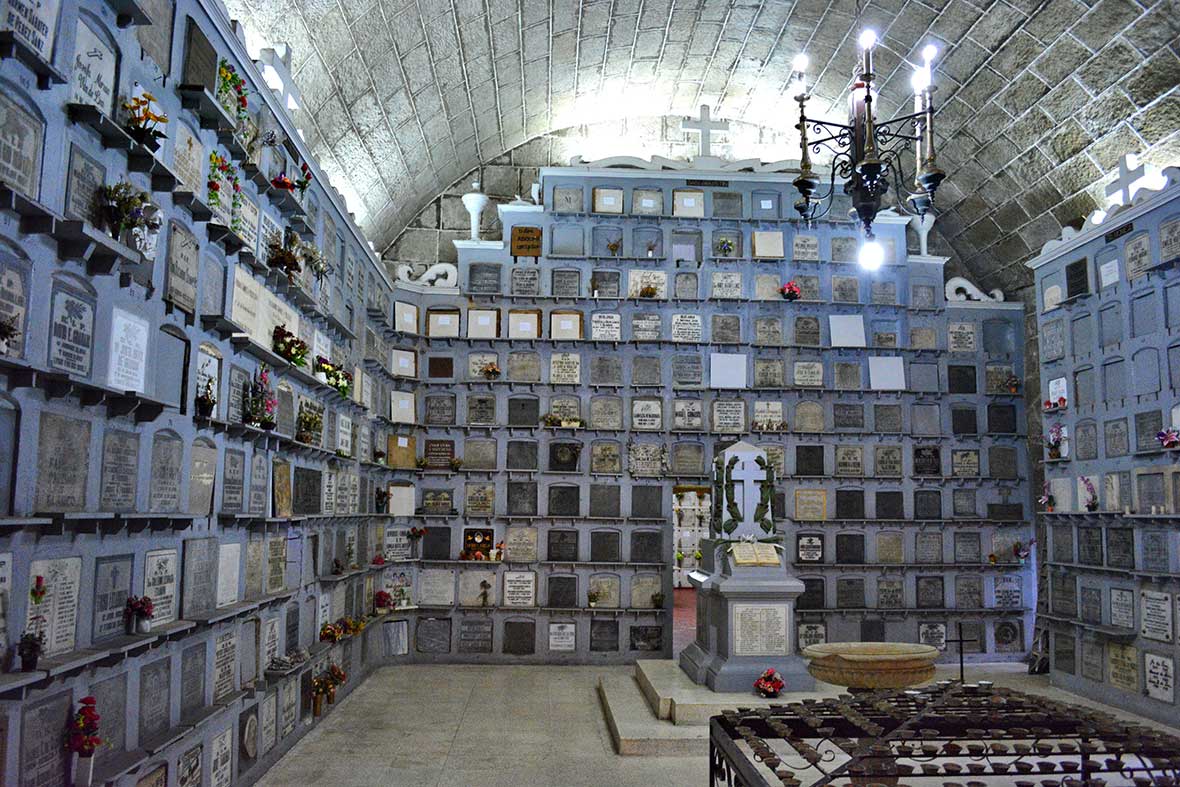

Chief among them are tourist draws San Agustin Church and Manila Cathedral. Perhaps the two most attractive religious structures in the city, they brim with visitors each day. The former, built in 1574, has a splendid Baroque exterior which gives way to a photogenic interior, embellished by detailed murals, complex stonework and an array of religious artefacts, including many fine paintings.

San Agustin Church is part of a scattered UNESCO World Heritage Site, called the Baroque Churches of the Philippines. The four churches in this one UNESCO listing symbolise perhaps the most lasting impact of the Spanish era – the spread of Christianity. To this day, about 80% of Filipinos identify as Catholic.

To the north of San Agustin, deeper inside Intramuros, is the even more remarkable Manila Cathedral. Whereas San Agustin captivates with its history and delicate architectural details, the cathedral stuns visitors with its sheer size. Built alongside the green and peaceful Plaza de la Roma, it stands more than 160ft tall and has a floor space of more than 30,000 square feet.

Yet this cathedral isn’t just a hulking stone structure. It too has exquisite craftsmanship, exemplified by dozens of hand carved statues arranged throughout its colossal main prayer hall. As the most important church in Manila, it at times attracts as many as 3,500 people to its masses. Particularly those on special occasions such as Christmas and Easter, when Intramuros hums with a festival-like atmosphere.

Such celebrations typically flow from the cathedral through to the manicured gardens of Fort Santiago. This military structure, at the northern end of Intramuros, hosts the Jose Rizal shrine. Opposite from that, tourists can wander the remains of a building named after another Manila hero.

The Rajah Sulayman theatre honours the Muslim warrior who was in charge of Manila when the Spanish first arrived in the Philippines. Sulayman led several successful defenses of this settlement, before eventually the invaders won out. Now, more than 400 years later, the tales of Rizal and Sulayman remain embedded in Intramuros, the grand Spanish citadel that was claimed by Filipinos and now is Manila’s most outstanding tourist attraction.