Before Northern Thailand became a part of Siam at the end of the 19th century, it functioned as an independent kingdom called Lanna (meaning ‘a million rice fields’).

In its heyday of the 14th–16th centuries, Lanna extended its rule far into present-day Laos, China and Myanmar. But by the 19th century, the illustrious name had fallen into disuse, and the kingdom splintered into local fiefdoms.

At that time, Chiang Mai was an extremely remote settlement, separated from Bangkok by a riverine journey that could take anywhere between six and twelve weeks.

This remoteness is reflected in the various forms of the city’s name. Ischeen Mey, Jamahey, Jangonia and even Zimme were different forms used, which one could be forgiven for suspecting were completely different locations.

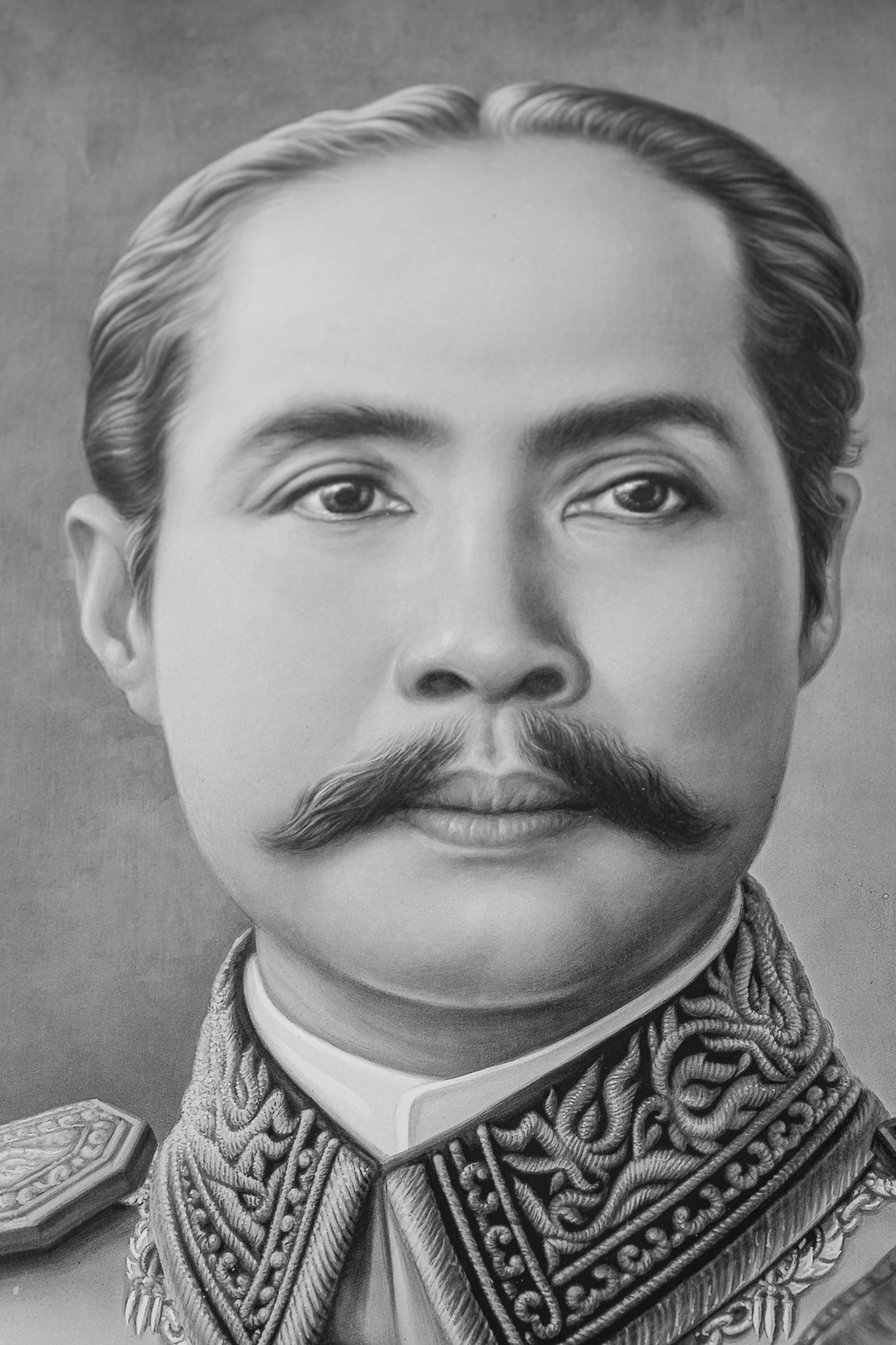

When King Chulalongkorn came to the throne of Siam in 1868, he probably gave little thought to his Northern neighbours, who posed no threat to his powerful kingdom. Yet as the century progressed, the colonial rampages of the French in Laos and the British in Burma gave him cause for concern that either nation might snatch up these northern fiefdoms.

Along with these disturbances across the border, Chiang Mai suddenly became the centre of a teak boom. Teak had been logged in the hills around Chiang Mai since before 1850, but when a shipment of teakwood from here was sold in Liverpool for a profit of 100% in 1882, the rush was on. The sudden spike in demand for teak was largely due to the European colonial powers’ drive to ‘rule the waves’, and teakwood was the ideal material for boat-builders of the time.

Teakwood’s great features are that it grows slowly, so its dense heartwood is not prone to warping, and the presence of silica in the wood acts as a deterrent to borers such as termites. Its leaves are big and floppy like elephant’s ears, and fortunately for loggers, the trunk grows incredibly straight and with few side branches, making it ideal for the sawmill.

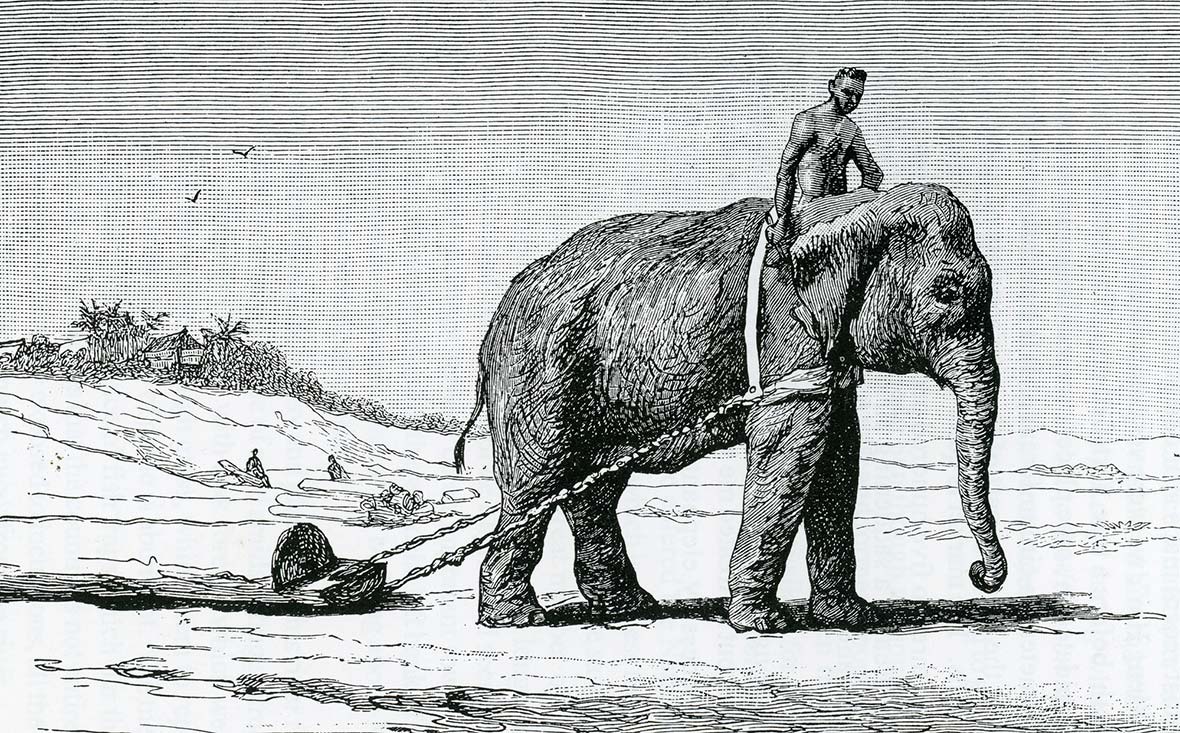

There were many steps in teak logging, and the whole process, from girdling trees to selling planks of teakwood at the sawmills in Bangkok could take five years or more. Girdling involved removing a strip of bark and sapwood from the tree’s circumference, which killed it within a few years. Felling was a particularly precarious process. If the tree fell the wrong way, it could split the trunk or crush the loggers, so wedges were shoved into axe cuts to make the tree lean the right way.

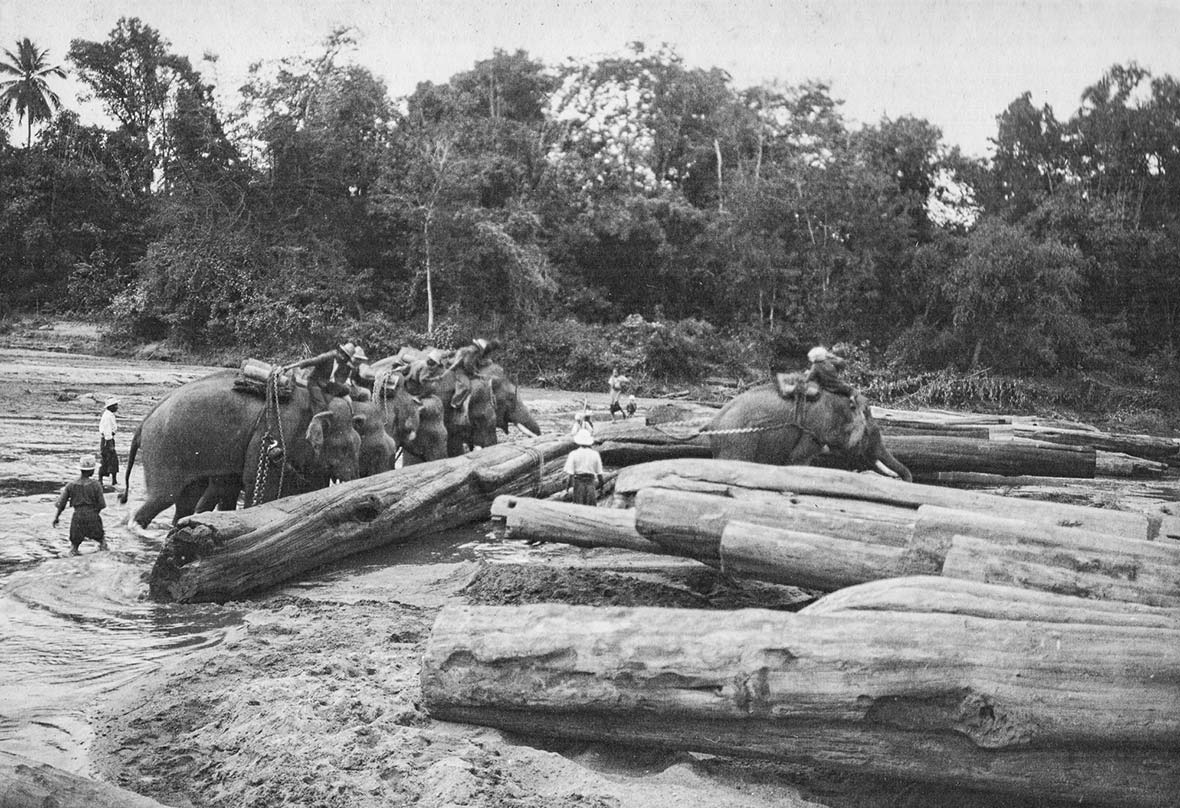

Once the trunk had fallen, it was cut into lengths that could be dragged by elephants to the nearest stream and later tied into neat rafts. The logs were stacked on the bank to await the rain season, when they would be floated downstream, eventually to Bangkok. In the 1880s and 90s, the Ping River at Chiang Mai was frequently choked with teak logs, and elephants were often called on to unpick the jam.

Years of drought could be disastrous, since the rivers would not rise enough to float the logs downstream, and the teak agents were left cursing their bad luck. Nevertheless, when conditions were good, teak trading could be a very lucrative business, and the teak lords built themselves lavish homes that were run by a retinue of servants.

One man who was ideally placed to take advantage of the teak boom was Doctor Marion Cheek, a medical missionary working with the Laos Presbyterian Mission in Chiang Mai. Cheek developed a close friendship with the local ruler, Chao Inthawichayanont, during evenings featuring boxing bouts, graceful dancing, drinking and gambling at the Chao’s palace.

This friendship brought Cheek teak concessions from the Chao and soon he was offered the job as Agent for the Borneo Company, which then became the biggest player in the local teak trade. Cheek abandoned his missionary work to follow his dream of riches.

As tends to happen, when tales of huge profits got around, everybody wanted to get in on the act, and soon the Bombay Burmah Trading Company, the Danish East Asiatic Company and the Siam Forest Company were clamouring for concessions.

One would-be teak lord who arrived in Chiang Mai in the late 1880s was Louis Leonowens, who happened to be a boyhood friend of King Chulalongkorn from the days when his mother Anna worked as a governess in the court of King Mongkut. He also worked initially for the Borneo Company and struck up a friendship with Doctor Cheek. They shared a fascination with local culture, including the baffling language, elegant dancing and delectable food, and even shared a harem of local beauties, though their friendship stopped short of sharing business secrets.

Readers keen to delve deeper into the escapades of these adventurers should check out the historical novel TEAK LORD by this same author, but for now, let’s track down vestiges of the teak lords’ presence in Chiang Mai that can be seen today.

One of the best examples of local heritage from the teak boom era is the main feature of the Anantara Chiang Mai Resort, a building that once operated as the British Consulate and now functions as an atmospheric restaurant, The Service at 1921 House. The restaurant consists of a concrete ground floor and teakwood upper floor, and both floors have breezy colonnades and verandas for outdoor dining, offering sweeping views of the Ping River as it flows by.

These days the restaurant is decorated as a hideaway for secret service agents, and a private room hidden behind false bookshelves heightens the intrigue. The downstairs Brit Bar has all the hallmarks of a quaint British pub, while the shiny leather sofas and walls in the Secret Agent Room lined with spy paraphernalia create the ambience of a private members’ club.

Though the Anantara treasures its architectural heritage, the menu of The Service 1921 is thoroughly modern. It would hardly be intelligible to guests from a century ago when dishes like Tasmanian lamb rack and Cajun-spiced cauliflower would have raised puzzled eyebrows.

Chiang Mai’s early foreign residents were mostly granted land on the east bank of the Ping River, and it was here that the Borneo Company built their office in 1889 under the tenure of Louis Leonowens. This now forms the centrepiece of the 137 Pillars Resort, and a new museum, Amid Teak Pillars, displays images and artefacts from the teak boom era. Guests can check in to the Louis Leonowens Pool Suite or the Rajah Brooke Suite and savour a six-course set menu or the delights of a Northern Thai curry in the Palette gourmet restaurant.

A stroll south along the east bank of the Ping River from 137 Pillars reveals a couple more reminders of the teak boom era. Just south of the Nawarat Bridge, the main bridge in town stands Chiang Mai’s First Christian Church, built by Doctor Cheek in 1889. Despite abandoning the Laos Presbyterian Mission, Cheek sought to improve life for residents of Chiang Mai by building hospitals, schools, churches and even the first sturdy bridge over the river.

Less than a mile further south on the east bank of the Ping, the Gymkhana Club, founded in 1898, may not boast an ancient clubhouse. But the view from its terrace has hardly changed in over a century, apart from the fact that the rain tree in front has grown even bigger. Beyond the rain tree, the green expanse of the golf course provides a fine background for an afternoon cup of tea or cocktail while reflecting on a bygone era.