The brush strokes are slow and delicate. Yet what is created is so bold and bright that it strikes me from across the room. I’m on the second floor of a Kathmandu building in a small, colorful studio inundated with color. Turquoise, pink, orange, gold, emerald, crimson, and cobalt collide on cotton scrolls painted by Nepali artists under the guidance of a veteran teacher.

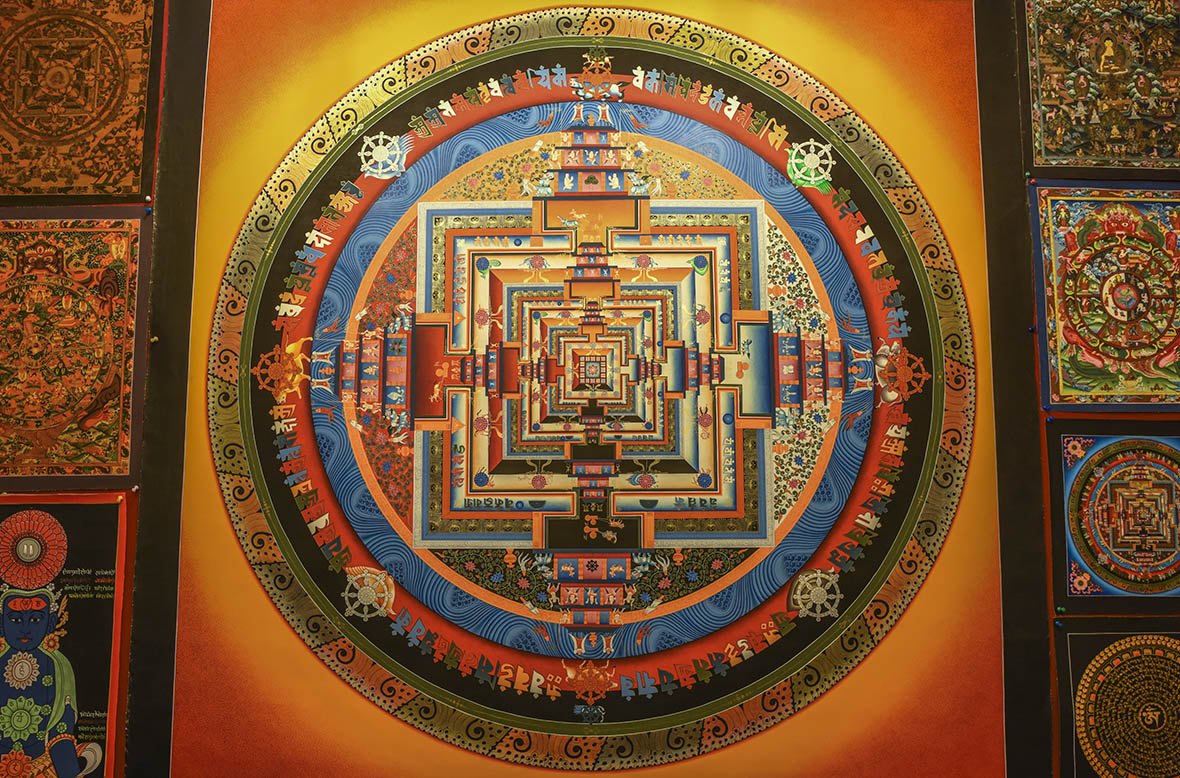

This spectacle extends beyond the color palette. The paintings portray dynamic depictions of cosmic trees, wheels of life, infinite universes, and fearsome deities. As I stare at one particularly complex piece, I find myself drifting away, no longer concentrating on the words of my guide, which are floating past me like the clouds in the artwork.

These paintings are hypnotic, I realize. And they are meant to be. For at least 1,000 years, Thangka paintings have acted as prayer aids, helping transport Nepali, Indian, Tibetan, and Chinese Buddhist worshippers into states of deep meditation. They remain common in Nepal, where they adorn temples, flank altars in Buddhist homes, act as focal points in Buddhist ceremonies, and depict teachings or events in the lives of Buddhist spiritual leaders.

Tourists will also spot Thangka sold by art shops throughout Nepal and embellishing perhaps Kathmandu’s most-visited attraction, Swayambhunath. A UNESCO World Heritage site, this shrine looms about the city’s west on a hillock, its white stupa shining in the day and glowing when the sun sets. Vivid Thangka art enlivens the monastery walls at Swayambhunath, which is believed to be more than 1,500 years old.

Nobody knows when and where Thangka first emerged. But it has diverse influences, fusing elements of Chinese, Nepali, Kashmiri, and Central Asian schools of art. In Nepal, it can be traced back to at least the 10th century.

Elsewhere, historians claim the world’s oldest existing Thangka hides beneath China. In Gansu Province, in China’s arid north-west, one of Asia’s troves of ancient art lurks in Magao, a huge cave complex carved into cliffs by humans more than 1,600 years ago. This UNESCO World Heritage site houses about 45,000sqm of murals and more than 2,000 painted sculptures, a Buddhist collection that dates back to the 4th century.

In Nepal, meanwhile, the anonymity of Thangka complicates efforts to date them, as they’re typically not signed by their creators. That’s because Thangka is made to venerate Buddhist deities rather than as a showcase of an artist’s talent.

While it takes enormous skill to complete these intricate works, the painter’s style is limited in its expression due to the custom of following ancient Thangka guidelines. These aren’t freeform paintings. But rather meticulous recreations of Buddhist deities, icons, and motifs based on popular representations.

Painting Thangka has long been a common practice for Nepal’s Buddhist monks. The slow, deliberate process is, in itself, akin to a form of meditation. This art form is not restricted to holy men, though. Or to men at all. That studio I visited was occupied by a group of female students guided by Bikash Titung Tamang, a non-monk with more than 20 years of experience making Thangka.

Bikash told me he grew up in an area just east of Kathmandu, called Kavre. There, in his home village, he saw a Buddhist monk drawing and painting magnificent Thangka. Fortunately, this monk took the time to pass on his skills to Bikash, who now makes his living from teaching, selling his artworks, and also conducting workshops for tourists.

Via Backstreet Academy, travelers can book either a four-hour session with Bikash to learn the basics of Thangka, or a 7-day masterclass to delve deep into this historic craft. Bikash told me Thangka was a great art form for foreigners as these paintings were embedded with stories that reveal elements of Nepal’s Buddhist faith. During his classes, he taught tourists some of the mythology fused in Thangka.

For most artists, the process of creating a Thangka remains similar to that of bygone centuries. The cotton canvas is stretched on a frame, then treated with milky limewater and glue to give it a more robust surface. Charcoal or pencil is used to sketch Thangka’s outline. Then that brilliant color palette is utilized, with mineral paints bringing the artwork to life.

Buddha, in varied forms, is typically at the center of a Thangka, often encircled by other deities. With his giant earrings and decorative headdress, Buddhist mystic Padmasambhava is one commonly painted deity. So, too, is Chenrezig, also known as Avalokitesvara, the beloved Buddhist figure that represents empathy and kindness.

Adding to the complexity of Thangka are wheels of life – symbolic depictions of the human life cycle – and cosmic trees, which represent the binding of heaven and earth. Not to mention the revered mandala, a diagram of an infinite universe laden with geometric patterns.

Tourists can join Thangka classes all over Nepal, particularly in the Kathmandu Valley area. Or they can just stand and admire, as I did. They may soon find themselves pulled into the colorful settings of these paintings, increasingly oblivious to their physical environment. That might be the millennia-old, mesmerizing power of Thangka taking hold.