James Hilton’s classic novel Lost Horizons got us all started with the search for Shangri-La.

While the exact location of the author’s mythical valley of bliss is purported to be in China’s Yunnan province, many associate the magical spot with Tibet, home to dizzying altitudes, snowy peaks, throat-chanting lamas in maroon robes, and exquisite monasteries soaring above craggy hills.

The reality of present-day Tibet of course is quite different, with plenty of red tape navigation required to visit, and current Chinese politics dictating just what you’re going to see and where you’ll be able to go.

Having bicycled across Tibet during its least restrictive times some thirty years ago, I knew I’d most likely find disappointment in returning. But on a recent trip to Sichuan with my wife, we found perhaps a more authentic version of Tibet than we would have had we gone to the real thing.

The western areas of Yunnan, Gansu, and Sichuan provinces border the Tibetan Autonomous Region, and are heavily populated by Tibetans. While Beijing has controlled the TAR with an iron rod, policies in the neighboring areas have been more relaxed.

And visitors can travel throughout much of the region without any special permits. It’s a Tibetan fringe that offers the intrepid traveler a glimpse of what Tibet, both physically and culturally, was like years ago.

After flying into Chengdu and doing the obligatory stop for a bowl of piping spicy Sichuan hotpot and a panda visit at the Panda Research Center, we boarded a bus heading west.

Within an hour, we’d left the haze and urban sprawl of the city and were climbing a winding road, with stunning views of the snowcapped four-peak massif of Siguniangshan, now a national park and UNESCO World Heritage site.

We crested the 4500-meter Balang Pass, and it was as if we’d pressed a button and entered a movie set, with China’s crowds and busy pace gone, replaced by a high altitude paradise, with beautiful hanging valleys below.

We descended into the county of Danba, known as “the kingdom of a thousand castles,” as the fertile valleys here are home to timeless villages that feature ancient stone towers. These were purportedly built to suppress demons but were then utilized by the Sui and Tang dynasties during the 6-9th centuries as both living quarters and fortresses for protection against invaders.

Danba is inhabited by both ethnic Qiang and Jiarong Tibetans, a group of pastoralists who have settled in lower altitude valleys that are far more fertile than those on the arid Tibetan plateau. This area was actually part of the traditional greater Tibet, which was divided into three areas: U Tsang in the west (which is where Lhasa and most of Tibet lies today), Amdo in the north (which now includes much of Qinghai province), and Kham, the eastern area extending almost to Chengdu, home to the ancient Tibetan warrior kingdoms and Khampas, a group known for their fighting prowess.

Today, the locals don’t come across as quite as fierce, as in Jiajiu, a small tower village where we’ve stopped for a few nights, the main square is full of happily inebriated old locals, playing checkers, gossiping, and watching the world go by. A trio of old men in leather cowboy hats call us over to share in a few shots of potent chang rice wine and direct us to walking paths up to the stone towers, where we have fabulous views over the lush valley.

We gulp in the heavy air and relish the ease of walking, as this will be our last day below 3,000 meters. From Jiaju, the main road climbs steadily into the Garze Autonomous Prefecture on the Tibetan plateau, where a high altitude grassland carpets an undulating plain where yaks and sheep graze in abundance underneath massive snowcapped peaks. We call in at Tagong, a village set at the edge of the grasslands where the glistening 100-kilogram gold roof of the Muya Golden Pagoda and Lhagong Monastery are lit up by the unfiltered high-altitude sunlight, with the immense 5820m jagged Yala Snow Mountain serving as a dramatic backdrop.

Traditional stone Tibetan homes dominate the the town, and in mid-May, it’s full of semi-nomadic herders wearing thick sheepskin coats, sorting out their tents, horses, yak teams, and provisions in preparation for setting out into the grasslands for the summer. While many of the towns in Tibet proper have been turned into Disneyfied versions for mass domestic Chinese tourism, places like Tagong have been spared. Here, small scale Western-traveler hangouts remain as opposed to gaudy high rise hotels, and local eateries serve up plates of steamed momo dumplings, and noodle soups with dried yak meat to a mix of adventure travelers, Chinese long distance cyclists, long haired Khampa cowboys, and bevies of monks and nuns who have come to make pilgrimage to the gompa (temple).

A few hours up the road, the scenery and cultural experience become even more other worldly. In the mountains above the prefectural capital of Garze, a dead-end road into the isolated Peyul valley leads into Yarchen Gar, the site of one of the world’s largest Tibetan monastic complexes. Set on an island at 4,000 meters, Yarchen Gar at its height was home to over 10,000 Buddhist monks and nuns, in fact it was home to the largest Buddhist nun population in the world.

The Chinese authorities have closed the area to foreign visitors on and off over the past decade, and have also razed parts of the island in an effort to decrease the sheer numbers of practicing Tibetan Buddhists, and we weren’t sure we’d even be allowed to visit, but a perfunctory police check of our passports was all we needed to reach this remote spot, made all the more surreal by a May snowstorm occurring as soon as we arrived, the white snowflakes creating a tremendous contrast with the masses of maroon robes on the practicing monks and nuns who walked by oblivious to our presence, concentrating on reciting mantras, attending lectures, and retreating to small shacks set on the surrounding hills, where they do several-week self-meditation retreats.

From Garze, the G317 Tibetan Highway weaves west, alternating between narrow and precipitous river valleys and high snowy mountain passes. In the old days, travellers had to cross the scary 5,050 meter Tro La pass, where rockfall, landslides, altitude sickness, and all-too-often faulty bus brakes made for rather harrowing journeying, but now there is a tunnel through the mountains, which eventually arrives in the pleasant town of Dege (also known as Derge), set up above the Sèqū River, and the last point before crossing into to Tibet proper without a tour and the necessary permits.

Dege though is worth the arduous trip out and back, as besides its beautiful setting above the river with gaily painted timber homes surrounded by striking mountains, it is home to the Dege Parkhang, a traditional Tibetan sutra printing house that contains over 300,000 woodblock prints, dating back to the early 1700s, the largest collection of its kind in the world. Tibetan scriptures and books are made here almost exactly as they were when the Parkhang opened in 1729, handprinted from hand-carved wooden blocks. Some thirty printers are used to churn out over 2500 pages per day, and pairs of devoted workers sit in the cold and smoky rooms, rolling ink onto the blocks, attaching paper to them, and then drying them to assemble into books.

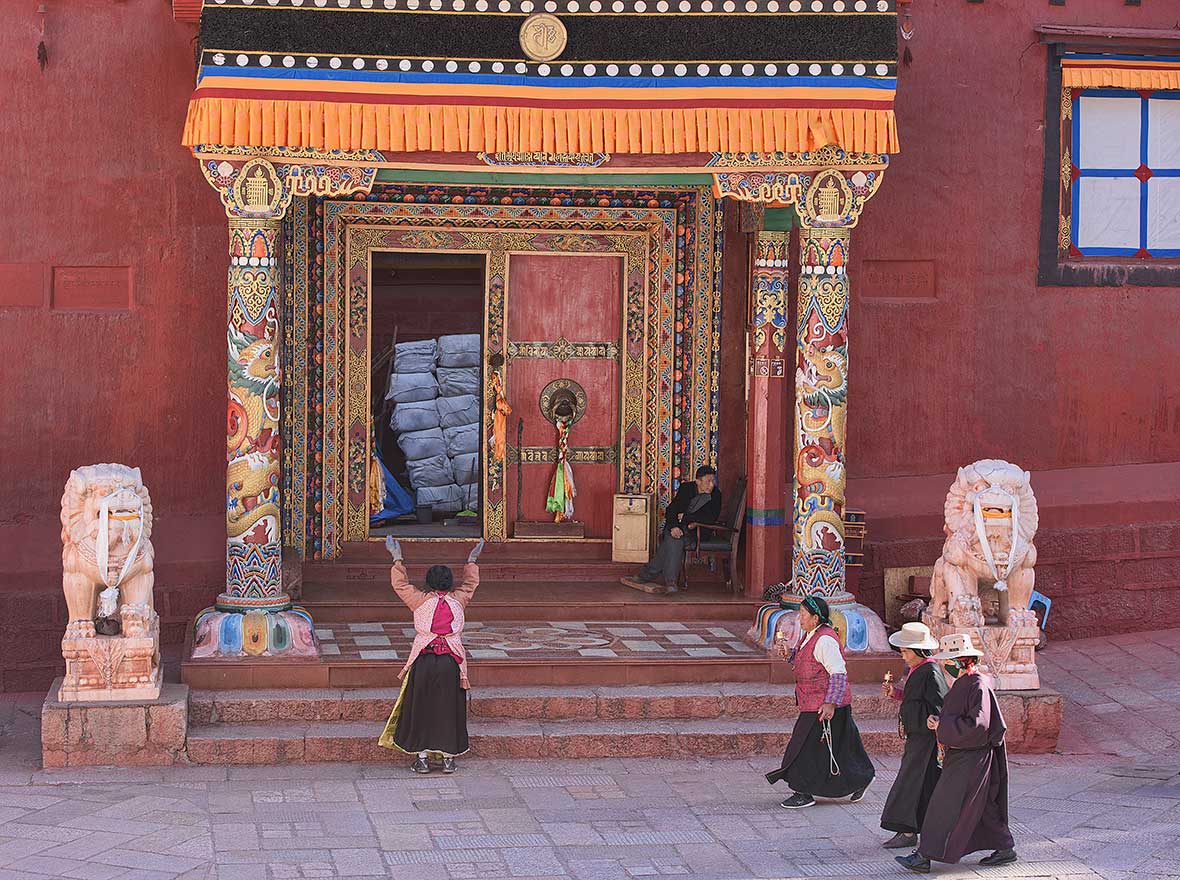

The Parkhang is not only a printing house and library, but also a highly revered place of worship. The building looks like a traditional temple with its dark crimson fort-like walls, and it is thronged by thousands of Tibetans during the day, most of whom either briskly walk or even prostrate themselves in a series of seemingly endless laps around the building. These circumambulations are known in Tibetan as kora, used as a way of making merit, but given the kora we’ve witnessed everywhere here in Tibetan Sichuan, from up on the grasslands at Tagong, to the temples at Yarchen Gar, and here in Dege at the Parkhang, it also looks like they are a type of high-altitude aerobics, as well as an excuse for jovial social gatherings. Most of the Tibetans we encounter here come across as incredibly fit, as they do anywhere from 5-20 fast walking laps (at 4000 meters no less), and afterwards everyone retreats to the local teahouses, where the beverage of choice is freshly churned yak butter tea, served alongside plates of steaming buffalo momos.

Wandering around the old narrow lanes of Dege, we come to the Gonchen Monastery, where a large crowd of locals have gathered. A Chinese woman next to us can speak some English and I ask her what is going on. She tells us that there is a purification festival happening today, and that the Gonchen monks will be putting on masks and dancing as part of the rites.

Within the hour, an orchestra of monks are blowing long alpine horns, crashing cymbals, and beating gongs, as a dozen monks dressed in amazingly colorful costumes that feature gilded aprons, ornate headdresses, and cowhide boots emerge from inside the monastery walls and begin to slowly twirl in rhythm across the courtyard.

We look around and survey the crowd, noticing that it’s almost all locals. There are a smattering of Chinese visitors, and we are the only foreign travelers present. This isn’t a version of Tibet for tourists, but the unadulterated real deal, and I think to myself that I’ve found my own version of Lost Horizons here on China’s Tibetan fringe.