Bent over the neck of his Tibetan pony, a man with a long braid recites a series of mantras. Hardened by high altitude winds and unforgiving sun, he looks like a clay warrior on horseback. Humming in prayer, he caresses his horse on the side of its head to pass on a good luck spell that seems to reduce the voices of the hundreds of spectators around him to a whisper. They all sit at the sides of the racetrack, holding their breaths, anxious for this horse to dash forward.

At last, the rider opens his eyes and raises his right hand to the sky. A colorful silk ribbon connects his fist to his horse’s mouth. He tugs lightly, and the horse begins to gallop. As mount and rider gain speed, the crowd’s low murmur graduates to excited shouts that echo across the green plateau and the grassy mountains around us.

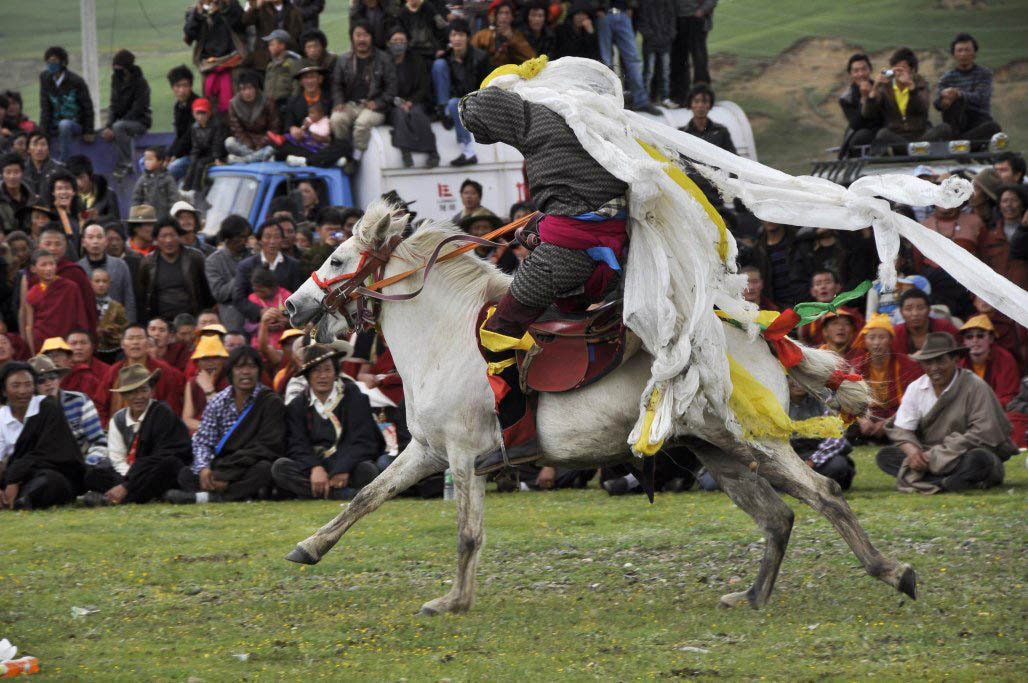

Thumping hooves spray chunks of black earth in their wake as the horse swerves to the center of the racetrack. Suddenly, the rider bites the reins of his makeshift bridle and lets his upper body fall to the side of his mount. His torso and arms float in the air while he clutches the horse’s flanks between his legs, as his feet are still firmly planted in the swinging stirrups.

I gulp down, for it’s the first time I see such a dangerous stunt for real. When the horse approaches a low mound in the middle of the racetrack, the rider swings his body and grabs a stone perched on top of it. He made it: as he lifts himself back onto his horse, the crowd’s powerful roar cracks the quiet of the grasslands, and leather cowboy hats wave madly in the air. As another rider takes position at the start of the racetrack, the cheers fade again into the silence of anticipation.

I close my eyes to find relief from the blinding sun as the horse nervously scratches the grass with its hooves. Before it dashes forward, I wonder if what’s happening before me is real or just the effect of high-altitude intoxication.

At 4014 meters in height, Litang is one of the highest towns in the world. Capital of the namesake county in the Tibetan Kham region of Eastern Tibet — now the southwest Garzê Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture — today Litang lies in the western part of Sichuan province. It’s here that, at the beginning of August, an annual horse festival fills the town’s grassy plateaus with thousands of Khampas.

These nomadic herders come from all over the Tibetan Autonomous Region and the former eastern Tibet states of Kham and Amdo, which now straddle parts of China’s Sichuan, Qinghai, and Yunnan provinces. In Litang, the Khampas race for honor and prestige: by competing for the best horse, they establish their nomadic socio-economic hierarchies.

However, witnessing this show of manhood is not an easy task: no outsider knows the precise date or the exact location of this festival. In fact, Khampas prefer to keep the whereabouts of their annual gathering as secret as possible to avoid attracting unwanted attention.

We were lucky: once we had reached Zhongdian/Shangri-La—the famous town that marks the beginning of the Tibetan world in northern Yunnan Province—at the end of July, we learned that this Tibetan horse festival is usually held for only one day at the first half of August. Crossing our fingers, we decided to try our luck and travel to Litang to seek it out.

In Daocheng, the first sizeable Sichuanese town, we hitched a ride along a tiny concrete road that snaked amidst rolling green hills and clear streams. “The horse festival is coming up,” said our driver, a tanned Khampa who kept his cowboy hat and sunglasses inside the car. “It’s the best time to be in town. But, I don’t know the date.”

We were still crossing our fingers as we checked into a local guesthouse and asked the Tibetan landlady if she knew anything about it. She wore a long black skirt and a woollen jacket, the most effective defense against the plateau’s cold winds. “Walk towards the grasslands out of town, and you will see the encampment,” she answered politely, promptly explaining that the horse festival would take place the next day. My heart started beating faster.

With a full day ahead of us, we set out to explore Litang. Its main thoroughfare is lined with Chinese restaurants and shops. But black-and-maroon-clad Tibetan men kept zooming past us on motorbikes adorned with colorful rugs and leather stripes cascading from their handlebars. Following the road they’d taken, we came to a place where the road branched towards the hills. We kept going, past the statue of Tibet’s hero, King Gesar, on horseback until the road narrowed. Maroon and golden Tibetan houses emerged along both sides of the road, starkly contrasting against green slopes and an intensely azure sky.

Clusters of square maroon houses continued to line the sides of the street until the road became a steep gravel path. Breathing heavily with each step, we hiked up the green mountain until we reached a bend halfway through the slope. The Ganden Thubchen Choekhorling Monastery walls lay between two grassy bends, its golden pinnacles, and red bricks so colorful that they seem alive against the blue sky. Inhabited by the Gelug-pa monastic sect, this place is a stronghold of Tibetan history: In fact, not only were the seventh and tenth Dalai Lamas born here, but it was also here that the Tibetans resisted the attacks of the People’s Liberation Army in 1956.

Inside the temple adorned with traditional thangkas, creaky wooden steps climbed up through the darkness and onto the roof, where fantastic views of Litang and the surrounding valleys opened before us as if we were looking into a sea of green. From here, we could see that the new Chinese-built thoroughfare was the only non-Tibetan part of town. Further away in the distance, the festival grounds lay just outside town. Smoke wafted up in the sky from metal chimneys that jut out of white Tibetan tents as if they were black spoon handles sticking out of vanilla ice cream scoops.

We rose early the next day to go to the festival grounds on foot. As soon as we arrive, people and animals are draped in colorful costumes, and traditional robes are mixed. Horses have ribbons of white, blue, orange, green, and yellow tied under their tails and around their flanks, adorning them in the colors of Tibetan prayer flags. People swing handheld Tibetan prayer wheels, waiting for the races to start and smiling at us as we pass.

The clay warrior and his dive to grab the stone from the mound is the first to rush ahead of the starting line. We are still dropping jaws when he dismounts, still holding the stone in his raised fist. A group of yellow-clad monks congratulated him, and I realized that I wasn’t under the effect of high-altitude intoxication after all.

A local Khampa lady, her hair twisted in braids, and a shiny array of jewelry dangling from her neck and wrists, talks in Mandarin to my wife. “That rider just qualified for the races,” she says.

One after another, men of all ages take on the challenge to the frenzied cheering of spectators. Suddenly, one rider bends down to reach for a white scarf slung around a pole, misses it, loses his footing on the stirrups, and falls off his horse. A hush immediately falls over the crowd, and only once the man lifts himself up unscathed and dusts himself off with a sour face, they start laughing.

Then three men on horseback prepare to race against each other by lining up next to each other at the beginning of the racetrack. “What are they racing for?” I ask a person who understands my English. He looks at me with a bemused expression.

They run for honour and respect. There’s no real winner: the faster the rider, the more prestige for his whole clan.

“Win? There’s nothing material to win here, certainly no cup,” he remarks. A white horse with a man in a brown poncho bent over its neck zooms past, lifting chunks of fresh grass in its wake. Racing behind it, another man pulls at the bridles, inciting his horse to ride faster.

“So, what is the point of this entire spectacle?” I ask. The man puts a hand on my shoulder and points at the winning white horse when it crosses the imaginary finishing line marked between two wooden poles.

“They run for honour and respect. There’s no real winner: the faster the rider, the more prestige for his whole clan,” he enlightens me before hooting happily as a couple of competing horses thunders past us.

I finally understand. I have come all the way to the vast plateaus of Tibet, where there are no fancy cars or clothing, thinking it was about one rider, one winner, one prize. But what I learn about this festival, where men vie for prestige, is that it’s all about the clan. They ride for their people and perhaps, if they impress a beautiful Khampa lady, to find a wife.