“Stay where you are,” whispers my guide Aziz as I prepare to negotiate the short final ascent over the cliffs and onto the beach at Ras Al Jinz Turtle Reserve. By the urgency in his tone, I’m concerned that something is amiss.

Perhaps my clumping steps as I approach the biggest turtle nesting ground on the Indian Ocean are upsetting the ever-delicate balance between nature and mankind?

I’ve already been informed, after all, that care and mindfulness are imperatives when it comes to interaction with the green sea turtles that come to this – the eastern extremity of the Arabian Peninsula – in huge numbers (roughly 30,000 per year) to lay their eggs.

ABOVE: Newly hatched turtles head for the sea at Ras Al Jinz.

Gentle creatures, green sea turtles are as vulnerable as they are beautiful. Long-standing existential threats posed to the amniotes by humans include overharvesting of eggs, the hunting of adults for food and being caught in fishing gear.

More recently, the insatiable march of development for real estate has resulted in the loss of nesting beach sites. Little wonder then that the emphasis at the reserve – a designated protected area since 1996 – is on the lightest possible footprint.

It’s not my utilitarian walking style that is giving Aziz pause though. It’s the fact that he wants to ensure I appreciate the full majesty of what I’m about to witness. “It’s a full moon night habibi,” he continues. “Plus, you are here in the middle of summer, which is the main season that the turtles lay their eggs. There is no better time to see the turtles. Prepare to be amazed.”

ABOVE: Turtle laying her eggs in the sand of Oman.

Sure enough, the ensuing scene does not lack for optics.

With the night sky supplying spectacular houselights, it’s easy to spot turtles laying their eggs in the soft sand. As we move along the beach, the individual players in this moonlit tableau move into sharper focus.

I watch – awed – as a mother attempts to conceal her nesting site, large flippers sending sand flying as she tried to cover her tracks. A little further on, a newly-hatched baby turtle bobbles unsteadily over the churned-up beach as it makes its way towards the ocean.

ABOVE: The Chedi Muscat, one of the most luxurious hotels in the region.

The experience is at once humbling and otherworldly – adjectives that will be familiar to anyone who has spent much time in this remote corner of Oman. Although just 253 kilometres, the drive from The Chedi Muscat to Sharqiya, a swathe of sea, sand and mountain that marks the south-easternmost tip of the Arabian Peninsula, feels like an epic.

While the Sharqiya coastal highway, which opened in 2008, has simplified travel in the region, the presence of the rugged peaks of the Eastern Hajar range pouring down to deserted beaches and pretty, traditional-feeling towns like Sur, remains thrillingly elemental.

Harmony between nature’s timelessness and state-of-the-art modernity are also apparent at Ras Al Jinz itself. Established by royal decree in 1996, the reserve was created as a means of protecting the nesting grounds from encroachment by local fishermen and hunters.

ABOVE: The Chedi Muscat pool area at night.

With Oman’s unique blend of natural beauty and enchanting Arabian tradition and hospitality making it one of the world’s hottest tourist destinations, visitor numbers to Ras Al Jinz have soared in recent times. A scientific centre was established in 2008, and was given a major renovation in 2017.

With advanced technology deployed to better understand the life cycle of amniotes, visitors can bone up on green sea turtles as well as the four other types of sea turtle (Loggerhead, Hawksbill, Olive Ridley and Leatherback) found in Omani waters. It is from the centre too that the two daily hour-long group tours – one at 8.30pm and one at 5.30am – to the turtle nesting grounds set off.

ABOVE: View from a The Chedi Muscat suite and the private beach.

Other draws, meanwhile, include an excellent international restaurant and a newly-minted concierge service, which can direct guests to other attractions and activities in Sharqiya including snorkelling, fishing trips and visits to the towering sand dunes inland.

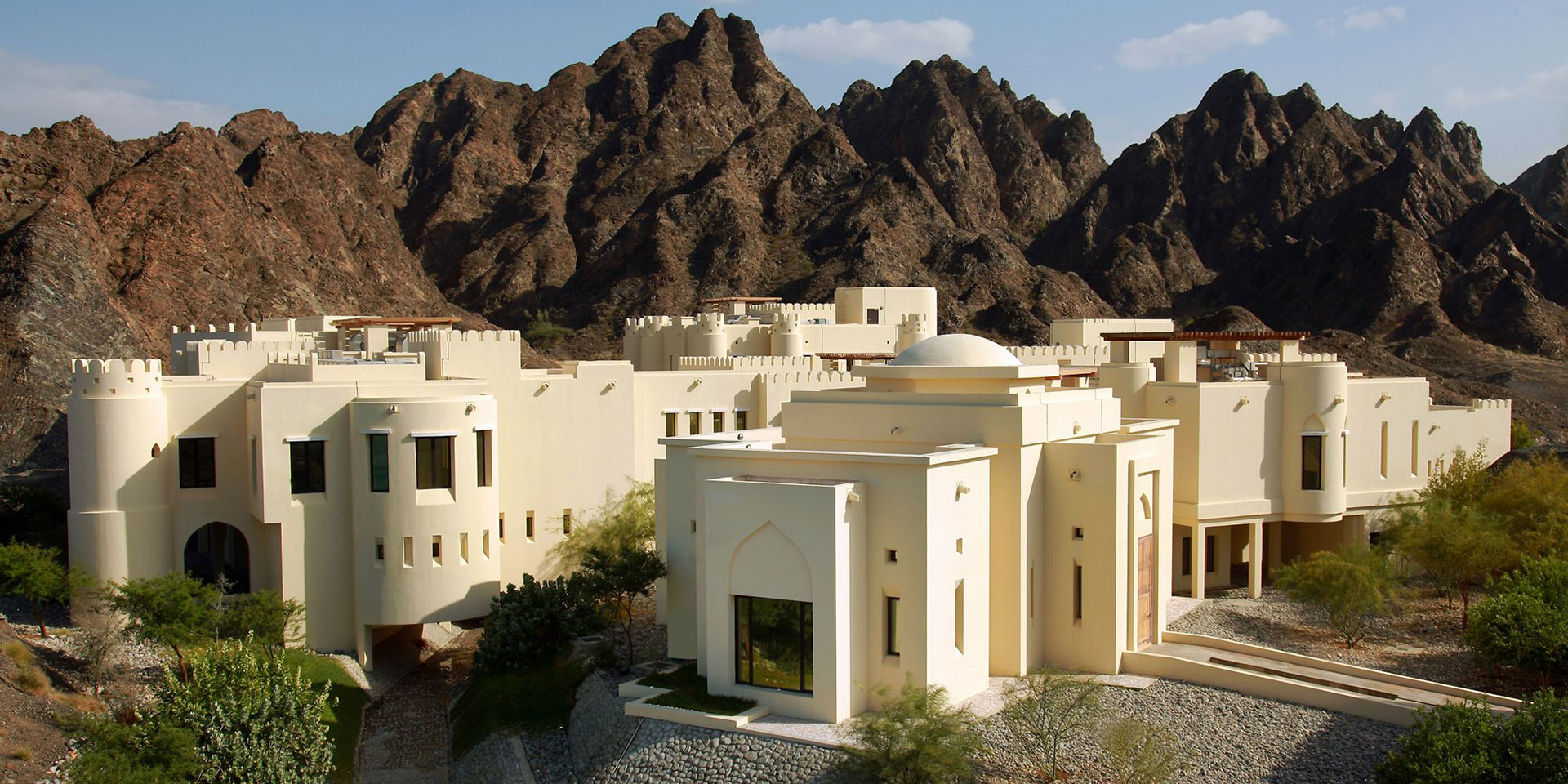

Such a multitude of trimmings are undoubtedly an excellent way of enticing guests to the reserve. Following my time in Ras Al Jinz, I reflect on the experience back at The Chedi Muscat, recalling the wild grandeur of the cliff-backed beach and its legion of nesting inhabitants. Despite the revamped facilities at the visitor’s centre, there remains something wonderfully wild and untamed about the hatching site. It’s a contrast indeed with the Moorish-style architecture and impeccable service at The Chedi. But it’s the creatures more than the creature comforts that really makes a visit to Ras Al Jinz sing, especially given my fortune in timing a visit to coincide with a full moon during peak nesting season.

ABOVE: Private beach at The Chedi Muscat.

“You did well to go there when you did,” laughs Quais Al Baluchi as we chat over drinks beside the Long Pool. Al Baluchi, an experienced guide who has visited Ras Al Jinz with guests on numerous occasions, is as breathless about the experience as I am. “Seeing the green sea turtles at their nesting grounds is a must-do activity in Oman,” he continues. “But it’s particularly amazing on a full moon night as you get the chance to see the complete process of laying eggs.”

A few days later, I find myself back at the beach on another tour, this time in the morning. I am compelled to make a second trip from the resort by the beauty of what I witnessed that full moon night. With a spare final day in Oman to play with, I make the return journey to Sharqiya. With the moon finally sinking in the sky, the turtles are more difficult to see, the scene is less active. As tentative shards of sun pierce the sky, bringing the first rays of light to the Arabian Peninsula, I spot one giant mother sitting still by the ocean’s edge. I move a little closer to try and get a better shot with my camera phone, but instinct prevents me from crowding it. After a moment, I let it be. At Ras Al Jinz you quickly learn that it pays to give nature its space.