The sex, murder, and intoxication caught me off guard. Such sordid topics were not what I expected to encounter at a small art gallery in Osaka. When I entered Kamigata Ukiyo-e Museum, I anticipated a change of atmosphere from the eerie, violent world of Fudo Myoo, a ferocious Buddhist deity I’d just visited in a nearby temple.

Instead, its ancient Ukiyo-e woodblock paintings sucked me into the bedlam of the Floating World. Scheming prostitutes, savage gangsters, fearsome Samurai, celebrity scandals, copious alcohol, and wild sex parties. These were the startling features of Japan’s Floating World, also known as Ukiyo.

In the 1600s, Japan’s feudal society was segregated, with four distinct classes—warriors, farmers, artisans, and merchants, in descending order of status. There was only one place they mixed freely. That was within the wild, walled-off districts of Ukiyo, where morals and piety dissolved in a cauldron of hedonism.

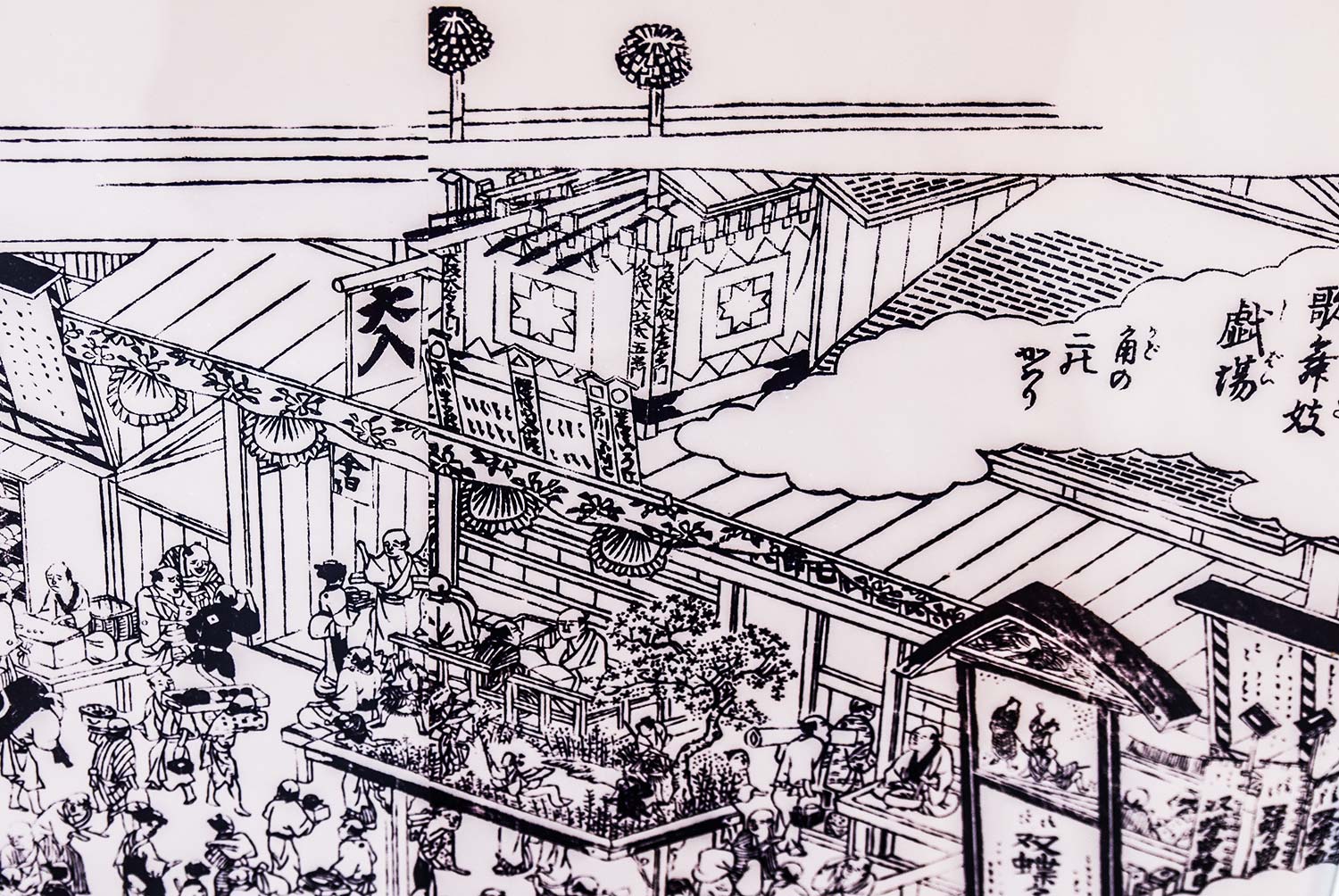

Now these sinners’ havens are in the spotlight. That is due to a recent exhibition of Ukiyo-e art, which offered a creative peek into this historic chaos. Ukiyo-e, which translates as “floating world pictures”, refers to the paintings, illustrated books, and woodblock prints depicting these seedy precincts which emerged during Japan’s Tokugawa period (1603–1867).

Earlier this year, the Kobe Fashion Museum showcased works which focus on the escorts of the floating world. These women have always been fixtures of Ukiyo-e images. When I began admiring the pieces inside that aforementioned Osaka museum, I didn’t realize some of the graceful, kimono-clad ladies that featured were actually courtesans.

This facility is in Dotonbori, a popular district with tourists due to its neon-drenched streets of restaurants and bars. The museum has a particularly large selection of Kabuki actor portraits. Dotonbori was a historic hub of Kabuki, a traditional Japanese performance art which fuses dance, mime, and theatre.

Kabuki stirred controversy when it emerged in the early 1600s, as its all-female cast danced seductively and, at times, portrayed prostitutes. This style of Kabuki was soon banned, for being too provocative. Yet it didn’t disappear. It just relocated to the anarchic environment of the floating world.

Ukiyo districts were then a fresh concept. The Japanese Government recognized it couldn’t simply erase the vices within its populace. So, instead, it sought to quarantine this hedonism. Rather than having prostitution, drunkenness and gambling embedded in mainstream society, Japan created three separate Ukiyo, in its biggest cities of Tokyo, Kyoto and Osaka.

These floating worlds became a place where everyday men could indulge fantasies without fear of shame or, to an extent, repercussions. Naturally, gangsters also flocked these precincts. Wielding weapons, dealing in vices, and dropping bodies, they pushed the boundaries of what was acceptable in the floating world.

Ukiyo districts weren’t entirely lawless. The most serious of crimes could still be punishable. But minor infractions, or deviant behaviour, were met with a blind eye. In Tokyo, saints became sinners as they passed through the infamous Omon gate to access Yoshiwara, the city’s gigantic floating world serviced by 4000 prostitutes. Most of these women were employed by one of more than 100 brothels.

When customers entered those red-light businesses, they were given lists of the women. Each was graded based on skills that extended beyond the bedroom. The most expensive courtesans were artistically gifted. They bewitched clients with their singing, poetry, and calligraphy. Securing a date with one of these sought-after women boosted a man’s status and was a popular display of power and wealth for Samurai, politicians, and gangsters.

Sex wasn’t the only dish on the Ukiyo menu, however. Its patrons also got drunk at rowdy bars, watched bawdy Kabuki shows, and ate to excess in restaurants. Then, with their urges purged, they passed through the Ukiyo gates and re-entered polite society.

Yet all this indulgence was a mystery to many Japanese people. Because the floating world was open to all. Many women, and men without sufficient money, never got a clear view of this murky setting, which is a key reason why Ukiyo-e paintings became so popular. As well as being a delicate and beautiful artform, they let everyone peer over the walls into the floating world.

Some Ukiyo-e were intimate portraits of escorts or Kabuki performers, like those exhibited recently at the Kobe Fashion Museum. Others, which I saw in Osaka, captured sprawling, disorderly scenes. They brimmed with drinking, dancing, and revelry. When I looked close enough, I could spot the different classes of men, from warriors to farmers. Here they were, shoulder to shoulder, in a heaving den of gratification. An untamed sphere of ancient Japan called the Floating World.