Two men have an Osaka audience in hysterics via a torrent of misunderstandings, double meanings, and cheeky puns. I can’t even tell what these Japanese comedians are saying. Yet their physicality, facial expressions and palpable chemistry have put a grin on my face.

Despite first emerging in the 9th century, Manzai, the old-fashioned style of comedy they’re employing, remains Japan’s most popular way of playing it for laughs. Manzai is performed by a duo, typically with one straight man (tsukkomi) and one funny man or fall guy (boke). In this way it’s akin to bygone double-acts like Abbott and Costello or Morecambe and Wise, with fast-paced banter complemented by physical comedy.

I’m not at a live Manzai show. Instead, the duo I’m enjoying—and the crowd they’re transfixing—is on a TV screen in front of me inside the Osaka Prefectural Museum of Kamigata Comedy. In fact, I’m essentially eavesdropping on this performance, watching it over the shoulder of a middle-age Japanese man who’s positioned right in front of the screen.

When he senses my presence, and turns around somewhat startled, I try to ride the comedic wave. So, I move left to look over one shoulder, then switch back to peer in over his right shoulder, before ending the physical riff with a wink. My admittedly weak joke does not translate. He just shakes his head and then buries it back into the more satisfying world of Manzai.

In most Western countries, it would seem unlikely that a 1,000-year-old style of performance art would appeal to the youth. Good luck getting a modern teenager to embrace slapstick American and British humor from just 50 or 60 years ago. But Japan does a remarkable job of safeguarding and embracing its cultural heritage.

Many ancient customs and artforms remain pertinent and even revered in contemporary Japan. Manzai is a fine example. It is so relevant, still, that each year it’s the focus of a huge, American Idol-style contest. That is the M-1 Grand Prix, hosted in Osaka theatres, televised nationwide and even streamed on Netflix.

Last year, more than 6,000 comedy duos took part in this competition. They were vying for not just the USD$75,000 first prize, but also the fame and generous opportunities that flow from making it deep into the competition. And this is a young person’s game.

The 2021 winners were the oldest to ever qualify for the final round, at 43 and 50 years old. Most previous winners had been aged in their 20s or 30s. Many of them aren’t rank amateurs who join the contest for fun, but rather serious comedians who perform on Japan’s busy Manzai circuit, which is akin to the stand-up comedy rotations in the US, UK, Australia and Canada.

Osaka has become the home of Manzai. That’s because the prevailing style of Manzai, with its straight guy and funny man, was perfected in Japan’s second-largest city by a huge entertainment company called Yoshimoto Kogyo, which continues to produce most of the country’s biggest Manzai duos.

Tourists who seek out Manzai shows, which are available across all Japan’s major cities, will find it differs from Western stand-up comedy not just in execution but also in subject matter. Stand up tends to be edgy, with topics that can err towards the flammable. Leading stand-up comedians like Dave Chapelle, Louis CK and Ricky Gervais actively court controversy, and revel in saying what supposedly shouldn’t be said. In comparison, Manzai is very benign.

Politics, sex, and hot button social issues are rarely explored. And if they are it’s done with caution. Manzai is mostly very family-friendly, like those, old-timey Western double acts. Often the funny man will say something naïve or dim-witted, which the straight man will comically misinterpret, leading to a prolonged interaction marked by confusion. Or the straight man will admonish and belittle the funny man.

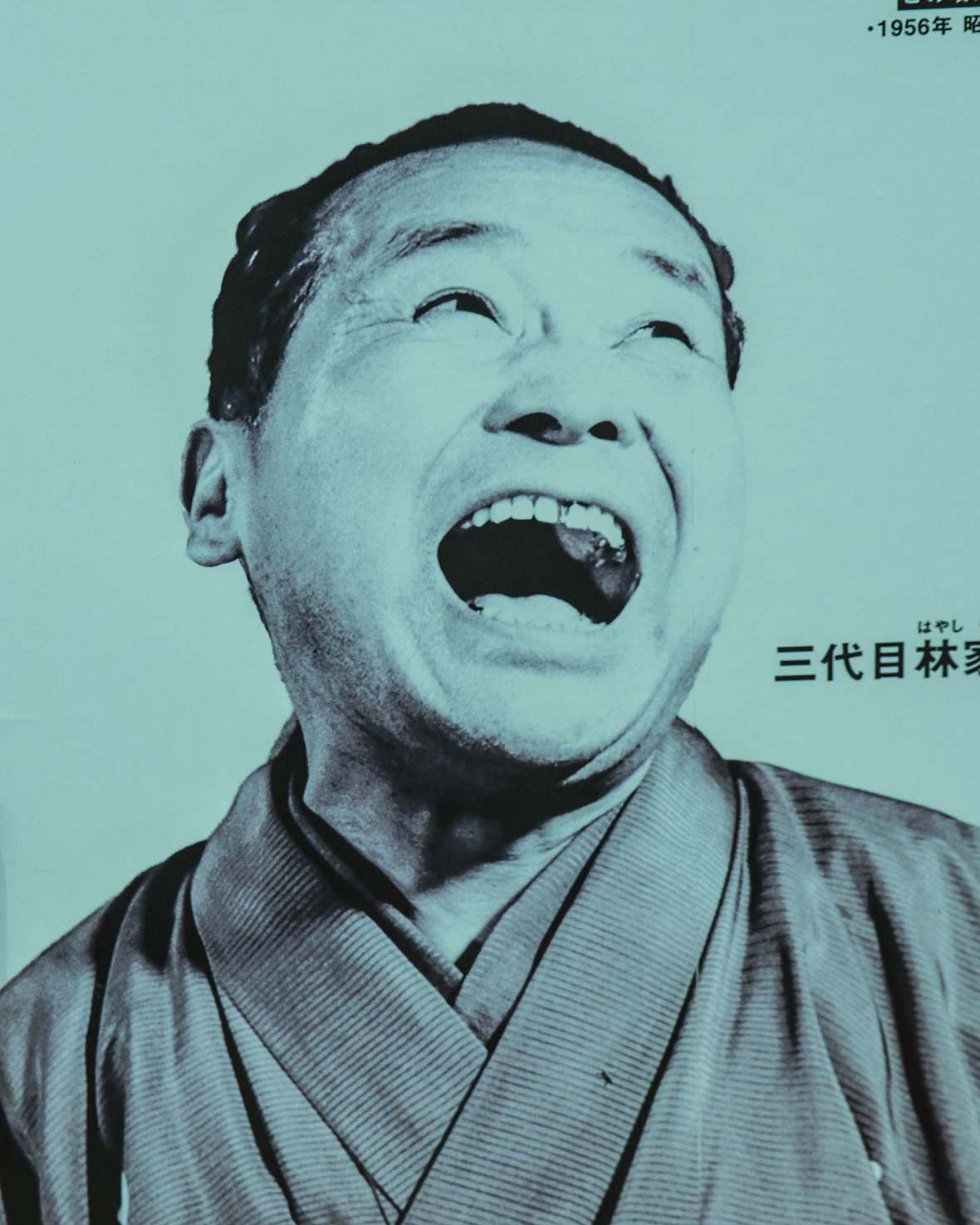

The museum in Osaka is the best starting point for a newcomer to Manzai. A bank of booths, each equipped with a TV, allows visitors to choose from more than 3,000 video and audio recordings of Manzai, dating back more than 80 years. Via its array of English language exhibits, the museum also details the history, themes and evolution of this comedy, and highlights some of its seminal performers.

Manzai began in the 9th century with a folk art called Senzu-manzai, the museum explains. Rather than performing in venues, these early duos would go house to house, dancing, singing, and telling a back-and-forth tale with its roots in spirituality. While these exchanges could have elements of humor, the museum states, it wasn’t until the 1600s that Manzai became heavily comedic.

By that point, Manzai comedians were among the most popular entertainers in Japan. They travelled from community to community drawing large crowds. These days, very little about Manzai has changed. Except that now this old-school form of comedy is transmitted direct to its millions of viewers via their televisions, laptops, tablets, and smart phones. It seems that the Japanese are firm believers in a familiar adage when it comes to their comedy. That is: if the tsukkomi and boke ain’t broke, don’t fix it.